In the gallows humor of this thing called Life, it’s usually in the afterglow of fulfilling our ultimate dreams that we wake up and ask, “What in the hell was I thinking?” Was it worth delaying marriage, foregoing children, neglecting aging parents and ignoring friendships, to find myself in my late-40s with a career fat with trophies and a heart vacant of every vestige of joy? Or was it worth missing my daughter’s dance recitals, my son’s soccer games, and shuffling into a roommate relationship with my soon-to-be-ex-spouse so I could be The Biggest and Best in other arenas of life?

And you know what really hurts, don’t you? This crushing epiphany happens, almost without exception, only after we’ve squeezed every drop of life out of ourselves to win the coveted gold stars. In the image of David Brooks, we’ve scaled “the first mountain,” only to realize that much — if not most — of what we’ve done was to make ourselves demigods of little winter peaks where a hypothermia of the soul soon sets in.

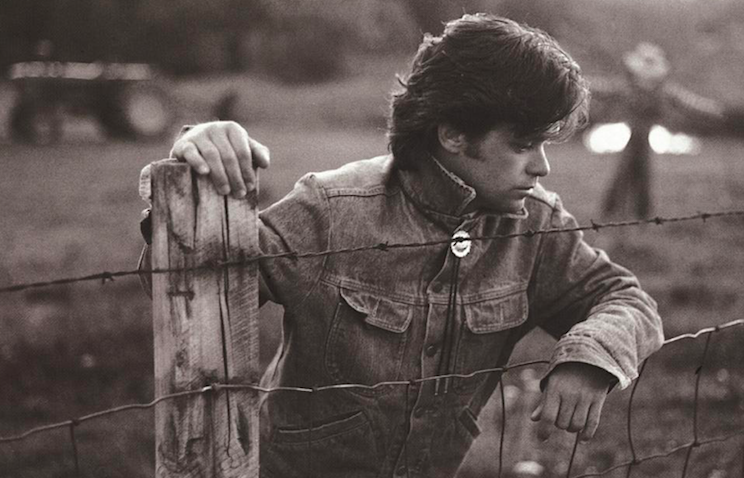

“Oh, yeah, life goes on, long after the thrill of living is gone.” Sing it, Jack. The thrill of living gradually evaporated in the heat of following our passions, in the odyssey of seeking that Thing that would make us Somebody. And here we are, in the noonday of life, drunk on nostalgia, high on loneliness, slouching with a graying Diane outside a dilapidated Tastee Freez.

These are the familiar haunts of the Noonday Demon. The Christian monks in the deserts of Egypt gave him that moniker centuries ago. He also goes by the name Acedia. In The Second Mountain, David Brooks refers to acedia as “a sluggishness of the soul, like an oven set on warm.” But for that most eminent of theologians, John Mellencamp, it’s simply when the thrill of living is gone.

You see, the Noonday Demon isn’t your typical devil. He’s totally down with being chill. Rather than making you foam at the mouth or glossolalia some ancient curse, he’ll plop down beside you on the couch while you binge-watch Netflix and polish off another bottle or three until you fall asleep, head back, mouth agape, only to wake up to kickstart another pointless, numbing workday designed to make you more money so you can perpetuate the ontological hell of your sad and hopeless existence.

That’s the Noonday Demon, the cheerleader of slow suicides.

There’s an ironic surprise, however, to a life molded by the Noonday Demon. Because precisely here, in the void of our seemingly empty lives, where the shades are drawn and the doors bolted, God drives up in a vintage Cadillac, kicks down our front door, and barges in with a grin on his face and arms full of grocery sacks bulging with the ingredients for a feast.

He does like his grand entrances, this party-loving, life-creating God. At the beginning, when he stood on the verge of a formless and void creation, staring down into the soupy nothingness of an unformed cosmos, he said, “Enough of this nonsense!” and spoke life and light and structure into being. He is the Almighty of verbs, let-there-be-ing this and let-there-be-ing that.

Nor has his modus operandi altered one iota. He still stands on the verge of our formless and void lives, reeking with the detritus of doomed dreams, graffitied with scars and bleeding wounds, where our souls have been flattened like interstate roadkill, and says, “Enough of this nonsense! Here’s a life I can work with anyway.”

When we’re finally at the point where—as Nick Lannon brilliantly captures it—we realize that life is impossible, life can really begin. Not a life defined by such verbs as conquer, succeed, achieve, surpass, accumulate but repent, believe, rest, serve, and hope. While we were out trying to conquer the world, we never learned to steward our own souls. So God shows up to take over, to do the impossible for us, to meet us in the nothingness we have become in order to love us into the fullness he always wanted us to have.

He’ll grab the Noonday Demon by the nape of his neck and kick his ass to the curb. Then he’ll haul five trash bags of empty successes and broken hopes to the dumpster. He’ll fire up the grill, heat up the oven, untap the keg, and ready us for the feast of a new life. This is how God rolls. Our sole contribution is pretty much staying out of his way.

He’s here to remake us, whether we’re 25, 45, or 75, or still holding onto 16 as long as we can. God is here to show Jack, Diane, and all of us fools that life is not about thrills anyway. It’s about dying to a deadness entombed in the deepest basements of our psyche that tells us life is an egocentric universe. It’s about dying to that lie in the death of God himself in the person of Jesus. And being shocked into a new life, suffused with light, as we stumble out of a tomb on Easter to find out we live in grace-centered universe empowered by nothing but divine Love.

On the other side of the first mountain, and through the valley of the shadow of death, we find ourselves in a novel world where we’re the most joyful when we forget that we exist. We’ve died and it’s no longer we who live but Christ who lives in us. Our total identity is subsumed in the God who barged his way into our lives, lifted us into the light, and fed us the feast of which his love and forgiveness are the main ingredients.

Long after the thrill of living is gone, we find life itself in the shock of discovering that the God of the universe names us his Beloved.

COMMENTS

4 responses to “A Little Ditty ’Bout Jack and the Desert Monks”

Leave a Reply

This is pretty much the best thing I’ve read in a long time. And the truly amazing thing is that we will forget the truths you spoke here, go back to chasing the gold stars, wind up miserable – and God will be there yet again, slow to anger and abounding in mercy.

This is most certainly true.

Spectacularly beautiful! Thank you.

This is such a beautiful and brilliant reminder that all my sorrows and regrets (at age 65) aren’t to be the final chapter of my life. I could read and reread this again and again. So much hope here! Thank you, Chad Bird and Mockingbird. Your words have lifted me countless times!