For reasons that were not clear to me at the time, and are still a little fuzzy, my family of origin hosted a stream of long-term houseguests when I was a child. If someone needed a guest room because of a poor choice in his marriage, or because she didn’t have a job that could quite make ends meet on her own, they found a home with us. And so I don’t really remember how old I was when David first appeared on our doorstep.

David wasn’t a lost soul without a place to stay, but he was a family friend who had an open-door invitation. He was a somewhat elderly “bachelor priest” — the unofficial term for our Episcopal clergy friends who never married. He was serving a church near my hometown but lived about 100 miles away. When my parents caught wind that he was driving to the church on Saturday nights (for Sunday morning services) and spending the night on a cot there without bothering to turn up the heat because God Helps Those Who Save Electricity, they put an end to that. At first, David was a reluctant recipient of our hospitality, preferring to serve in the role of host than that of guest, but he eventually came around to the idea of a warm meal and a place to stay, so long as he could contribute a bottle of wine.

After a year or two of this, David became a part of our family. I don’t mean that there were any official government documents completed and filed, but this was more than a loose invitation to hang out. It was assumed, I think, at some point, that he would just be there for every holiday, every graduation, and every wedding. He was ours, and we were his. Eventually, we found out that he didn’t have much of a childhood. Having grown up as an only child and only grandchild in the 1920s, he was familiar with bathtub gin during Prohibition and swing dancing, but it seemed that he didn’t have a good handle on the pursuits of American boyhood: slingshots and baseball and kick the can. He found this childhood in my family, trying out everything from video games to skateboards. One weekend, he brought slingshots to try with my brother. After a few disappointing rounds with pebbles and empty aluminum cans, David convinced my brother to try to shoot olives from his martini into his open mouth. By the grace of God, nobody died.

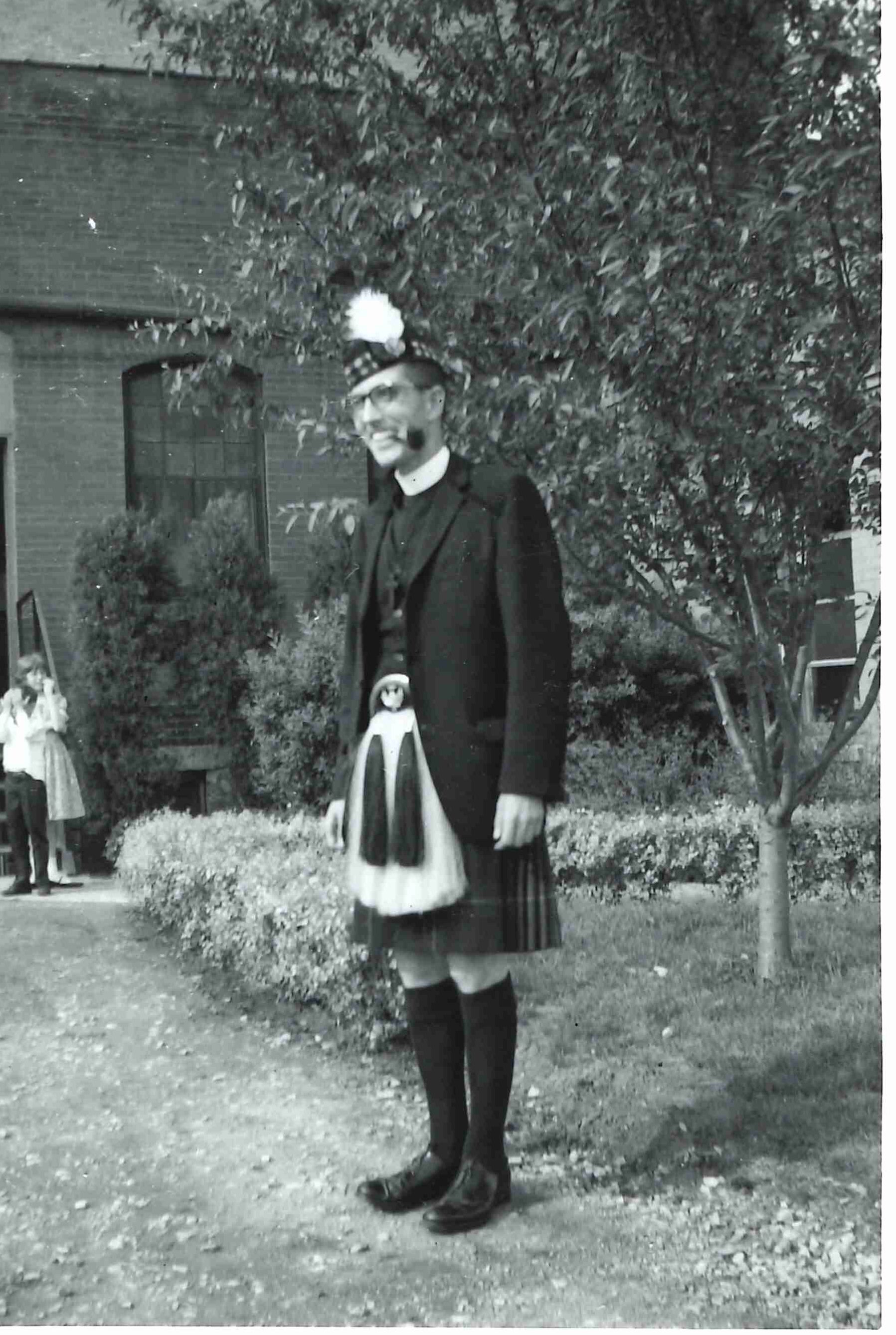

David was born in the United States, but his father was Scottish and his mother was English, and David spoke with an English accent. He was as British as anyone I knew in our small midwestern town. He smoked a pipe and drank gin martinis. He knew all of the answers in Trivial Pursuit, but he was always three or four questions behind, blurting out “Queen Victoria!” when we were already on an Elvis question. He bought my mother teapots, and he taught me how to make tea sandwiches with bread sliced so thinly “so that you can read the newspaper through it.”

David was a veteran of World War II and marched in the Battle of the Bulge. He was wounded and received a Purple Heart. He lost feeling in his fingertips every winter, even decades after frostbite ravaged his nerves. After the war, he went to seminary and was ordained to the Episcopal priesthood. He took a large part in raising his godson when his godson’s father died at a young age. When David was in his forties, a doctor told him that a heart condition was going to kill him within a year. He took that information with him when he learned Spanish and served as a missionary in Nicaragua. Fourteen years later, his heart was still ticking strong enough to survive an injury in the early days of the Nicaraguan revolution and then commandeer a truck which he used to save his neighbors and parishioners. He returned home to the United States, and shortly thereafter became ours. He was more comfortable talking about parties and canapés than he was about his dedicated service to others. Once, he and I paged through an entire issue of Martha Stewart Living so he could tell me how Martha was a hack and everybody’s been doing that party trick (on every page) since the 1950s at least.

David served as a Master of Ceremonies at my dad’s ordination to the priesthood when I was fourteen years old. He lined everyone up for the processional and kept a bunch of rowdy old priests in line that day. The weirdest thing about becoming a priest’s kid as a teenager is that you already feel like people are watching your every move, and then there’s an extra spotlight on you and your family that you didn’t ask for. David understood this, and shepherded us through the weird transition. On the same day of the ordination, my dad’s brother died, and David was there with us in our grief, too.

David officiated at my sister’s wedding and served as Best Man for my brother’s wedding. One of my nieces bears his last name as her middle name. By the time I was married a few years later, his health was failing. We invited him to our wedding in Virginia, but he couldn’t attend. He gave us his mother’s silver tea service as a gift, with a note in broken Spanglish in his choppy handwriting, because he could only emote in Spanish: “Dear You Two, Herewith please find my mucho más que merely best wishes — mi regalo de mi corazón y el mejor que yo tengo para su larga vida together.” Since he wasn’t well enough to travel for the wedding, I called him that morning. I don’t remember exactly what I said, but I’m certain that I said “David, we love you.” Old British men do not handle emotional displays well, and so only later did he confess that as soon as we hung up, he sat at his table and wept because he was so grateful to be part of our family.

David officiated at my sister’s wedding and served as Best Man for my brother’s wedding. One of my nieces bears his last name as her middle name. By the time I was married a few years later, his health was failing. We invited him to our wedding in Virginia, but he couldn’t attend. He gave us his mother’s silver tea service as a gift, with a note in broken Spanglish in his choppy handwriting, because he could only emote in Spanish: “Dear You Two, Herewith please find my mucho más que merely best wishes — mi regalo de mi corazón y el mejor que yo tengo para su larga vida together.” Since he wasn’t well enough to travel for the wedding, I called him that morning. I don’t remember exactly what I said, but I’m certain that I said “David, we love you.” Old British men do not handle emotional displays well, and so only later did he confess that as soon as we hung up, he sat at his table and wept because he was so grateful to be part of our family.

We don’t share any biological ties to David. His life became grafted with ours over time, like a less violent version of the olive branches grafting together in Romans 11:17. He is part of our family’s story as much as anyone who shares our DNA. His presence in our life is another way that our family math doesn’t add up to a tidy equation, but his addition brought joy in a way that another’s subtraction brought sorrow. My husband has never met my sister who dismissed herself from our family life, but he spent several long hours with David, and got to know me better by knowing him. Just as only God can reconcile some relationships, and even then maybe not on this side of the grave, God can sometimes surprise us with the joyful grafting of a David into our lives. This can feel like a small glimpse into the communion of saints, with “angels and archangels and all the company of heaven.” Our family math is complicated, but not always in a painful way.

David died shortly after my oldest son was born. We baptized our baby on the first celebration of All Saints’ Sunday after David died. My beloved father-in-law also died that year, and the baptismal waters my husband poured over our son’s head reminded us that we were baptizing him into a family of faith — not only the biological family that shows up on ancestry.com but also the grafted vine of our beloved David. When we sing “For All the Saints” as we did on that All Saints’ Sunday, I hear David and all of our foreparents in the third verse: “O blessed communion, fellowship divine! We feebly struggle, they in glory shine; yet all are one in Thee, for all are Thine. Alleluia, Alleluia!”

David was so well grafted into our family that I see glimpses of him in my own children, who never met him and have no biological tie to him. I see a glimpse of his orderliness and love of tradition in my eldest, and a sniff of his mischief and humor in my youngest. David would have loved exploring the world of Harry Potter with them, and he’d delight in the way that they carry on entire conversations in fake accents. I can only imagine the contraband he’d sneak into our house for them. His Nicaraguan congregation paid him in art, and we are fortunate that some of it graces our walls. Their bright colors fit into the very international city of Houston, just as David would have fit right in, too. He is still ours, and we are still his.

When David lined everyone up for the processional at my dad’s ordination, he was playing his part in our small family unit but also in the larger family of the church. He was the parade marshal, the drum major, the movie director. Just as he led his Nicaraguan friends out of danger in a commandeered truck, he led us through ceremonies and life changes and even his own grafting into our family. That day, we sang “Jerusalem, Jerusalem”:

There David stands with harp in hand

as master of the choir:

ten thousand times would one be blest

who might this music hear.

I’m reminded of David when we go to the Communion rail and we’re united again with him and “all the company of heaven.” We file back to our pew after Communion, and we pray a prayer of Thanksgiving for that Communion together. We thank God for assuring us that “we are very members incorporate in the mystical body of [God’s] Son, the blessed company of all faithful people; and are also heirs, through hope,” of God’s everlasting kingdom. Heirs through hope. Family members through God. All are One in Thee for all are Thine, and ten thousand times we’re all blessed by our grafted-in grandfather and the blessed company of all faithful people.

COMMENTS

4 responses to “All Are One in Thee for All Are Thine”

Leave a Reply

I have heard of dear David from your Dad and Mom, but you have brought him to life in this most beautiful tribute! A Gem!

This was such a comfort.❤️

This is beautiful.

wonderful, soul-stirring post, Carrie. But what i really want to know, comments-wise, is: where’s Dale?! I’m starting to get worried…