November 11 came and went as unexceptionally as any Sunday ever does, a day living under the permanent shadow of Monday, almost exclusively spent hoping against hope to recuperate before the work week resumes. Most Sundays, however, don’t mark one hundred years since the armistice that halted the First World War and gave the day its original name. One hundred years since the exhausted combatants of “the war to end all wars”, desperate to salvage a ruined Europe, stopped killing each other.

One hundred years sounds so distant, and yet we are so little removed from the generation that was eviscerated in the years 1914-1918. The social, political, and technological upheaval that characterizes the rest of the twentieth century seems to have landed in Western Europe during the summer of 1914, and we have simply spent the following century unfolding its corrosive contents. Something different took place during those four years, the repercussions of which we are still dealing with even now: a bomb blast that swept away a mythic picture of the nineteenth century and substituted the cruel, catered landscape of the twentieth.

Every soldier in every age has experienced the frightening chaos of battle and the confusion of having to overcome the inhibition against taking human life. But the Great War effected a profound dislocation and trauma the likes of which had not been seen before. In one sense, there is nothing unexpected about the loss of life in a war. But the sheer magnitude of the devastation in the years 1914-1918 was the stuff of ancient apocalypticism. In The World Crisis, Winston Churchill recorded that the war “differed from all ancient wars in the immense power of the combatants and their fearful agencies of destruction, and from all modern wars in the utter ruthlessness with which it was fought. All the horrors of all the ages were brought together, and not only armies but whole populations were thrust into the midst of them.”

Earlier in the previous century, Herbert Spencer had insisted that there existed a cultural analogue to biological evolution driving the development of human civilization. On the basis of an innate moral sense and an essential “perfectibility” to their nature, humankind would, he claimed, direct itself over the long run towards the greatest pleasure available, the freedom to take hold of it, and the peace to enjoy it. The forward arrow of “persistence of force” in social evolution was a guarantee of its inevitability. And the colonial powers of Europe had the firepower and the will to exert that force elsewhere around the globe on behalf of the poor benighted populations as yet unacquainted with the millennarian expectations of the West.

The astounding technological developments between the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and the outbreak of the Great War forty-four years later seemed to corroborate the West’s belief that they stood on the right side of history. It’s probably only natural, then, that many of these “enlightened” powers masqueraded their ideological fervor as religious duty. Each of the belligerent Christian empires, “in its way, regarded itself as a messianic nation destined to fulfill God’s will in the secular realm,” Philip Jenkins writes in The Great and Holy War: How World War I Became a Religious Crusade: “The war began as a clash of messianic visions.”

But it took the Christian nations of Europe butchering one another to expose the bankruptcy of this myth. By war’s end something like ten or so million soldiers had been killed in combat or succumbed to their wounds or to disease. Another six to eight million civilians died from starvation, disease, as collateral damage, and from ethnic cleansing. Battlefields such as the Somme, Ypres, and Verdun were simply unimaginable prior to the development of the sophisticated machinery of death unveiled in this war. Flesh and earth couldn’t withstand the power unleashed by such technology: the French countryside became an inhospitable morass of mud and artillery impact sites interring thousands of corpses. Human bodies were reduced to pulp by the firepower. Aircraft, poison gas, and tanks were later brought to the field to overcome the stalemate of trench warfare, and the systematic extermination of Armenians and Slavs added further horrific dimensions to the new industrialized age of warfare. The millions, both soldiers and civilians, sacrificed to the omnivorous gods of modernity bore witness to the emptiness of modernity’s conceits.

John Gray has written, “Whether secular or religious, myths are not refuted. Instead, they fade and vanish from the scene, together with the people who embody them.” True as this is, that practices vanish with their practitioners, the Great War also exemplifies how myth-makers and myth-wielders are seldom the ones directly struck the death blow. All too regularly it is the infantryman and the landing boat pilot who recognizes the explosion of the myth while the theorist safely ensconced behind the lectern prattles on about its grandeur and viability. Isn’t it obvious that we, the unremarkable, anonymous individuals that comprise the body politic are the primary sufferers when the illusions of statesmen clash with another illusion of greater brutal force? Myths die in the deaths of the unidentifiable masses who are led along by those myths’ mouthpieces.

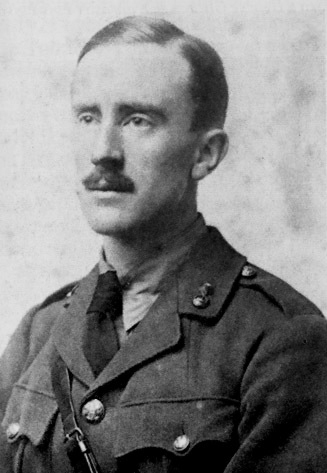

By 1918, J. R. R. Tolkien would later observe, with heartbreaking lucidity, that all but one of his close friends were dead. C. S. Lewis, likewise, lost all but one of his friends from the Officers’ Training Corps at Oxford. Their stories were nothing unusual — there were few households in Europe left untouched by bereavement to greater or lesser degree. What’s fascinating to me is how the hideousness of their experience in the war by all standards ought to have undone these men. Tolkien and Lewis were just as susceptible to become “broken, burnt out, rootless, and without hope…not able to find [their] way anymore,” as Erich Maria Remarque predicted would be the case for the millions of combatants processed back into civilian life at war’s end. But somehow, in spite of the inhumanity to which they were subjected, they would emerge in time as advocates of an orthodox Christianity that offered the world an alternative picture of what being human could mean.

The war signified more than a loss of life at a heretofore unprecedented scale; for Tolkien it was emblematic of the severance of everything beautiful and comfortable and humane he himself had once known. His early childhood in West Midlands with his beloved mother became to him an Edenic prehistory, a tiny concentrated dose of prelapsarian perfection in a quiet corner of the modern period. But this idyllic existence was blighted by her death when Tolkien was twelve years old. Prior to this, his father had died in South Africa when Tolkien was only four and a continent away. These griefs congealed into a deep-seated nostalgia for an irretrievable past cut off from us by a terrible Fall from grace. Even as of the time of his boyhood technological modernization was ravaging the countryside he loved and dismissing the customs of the past as irrelevant. An inchoate pessimism set into the young Tolkien which would come into full flower during the war.

The war signified more than a loss of life at a heretofore unprecedented scale; for Tolkien it was emblematic of the severance of everything beautiful and comfortable and humane he himself had once known. His early childhood in West Midlands with his beloved mother became to him an Edenic prehistory, a tiny concentrated dose of prelapsarian perfection in a quiet corner of the modern period. But this idyllic existence was blighted by her death when Tolkien was twelve years old. Prior to this, his father had died in South Africa when Tolkien was only four and a continent away. These griefs congealed into a deep-seated nostalgia for an irretrievable past cut off from us by a terrible Fall from grace. Even as of the time of his boyhood technological modernization was ravaging the countryside he loved and dismissing the customs of the past as irrelevant. An inchoate pessimism set into the young Tolkien which would come into full flower during the war.

As of the war’s beginning Tolkien was already at work on early versions of the mythical cycle that would in time become The Silmarillion and would provide him with the backdrop against which he could craft his masterwork, The Lord of the Rings. With the encouragement of his friends he drafted poetry and prose and painstakingly set about fashioning a millennia-long primeval history of the hubris of the world’s elder race, the Elves, and the destiny of those humans whose fate becomes entwined with them. But as his beloved friends fell one by one this sharpened the anguish that already shaped the stories. The culminating point was the death of his friend Geoffrey Bache Smith, himself a poet and believer in Tolkien’s gifts. In his final letter to Tolkien he wrote, “May God bless you, my dear John Ronald, and may you say the things I have tried to say so long after I am not there to say them, if such be my lot.” Tolkien resolved to bring his mythic history to completion both for his own soul’s sake and to honor the young men who had loved him and helped him pierce the darkness of his earlier losses.

Is it any wonder he should later write in his essay “On Fairy-Stories” that such stories offer both escape and consolation? That they illuminate humankind’s “oldest and deepest desire, the Great Escape: the Escape from Death”? From the beginning Tolkien’s mythology concentrated on the problem of how to live authentically in the face of death. The problem his stories expose is that many of the world’s evils take shape as human responses to the fear of death and the attempt to circumvent it. But all such attempts are doomed to failure and usher in only more death. How can death be something we are so pained to endure and yet something we must accept with something like gratitude at the same time?

In the older lore that Tolkien imagined before ever composing The Lord of the Rings, there was a cataclysm instigated by the men of an island kingdom called Númenor. Númenor was situated between Middle-Earth and the Undying Lands of the uttermost west and granted to the humans who had aided the Elves in their struggle against the first Dark Lord, Morgoth. They were blessed with the endowment of the Elvish art of civilization and streaming vestiges of the light of the Undying Lands. But Sauron sowed distrust among their leaders by provoking in them a terror of death they had not known before. At Sauron’s behest, the last king of Númenor dispatched a fleet to assault the Undying Lands and steal the secret of immortality. But as they approached its shores the semi-divine powers who dwelt there surrendered their government of the world and the One, the God of these stories, swallowed up Númenor with a cataclysmic flood, changing the shape of the world in the process.

The “breaking of the world” that took place ruptured Middle-Earth from the blessings of the Undying Lands which separated from the geophysical plane completely. Middle-Earth was left a curved world, closed in on itself, cut off from the bliss of the Undying Lands, left to its own devices. It experienced a disenchantment of its own as Sauron and the other heirs of Morgoth retrenched and built up their power. Memories of the past faded and many of the peoples of Middle-Earth forgot that death, while bitter, isn’t the worst fate imaginable for a creature. To progressively dissolve your own soul in the ultimately futile attempt to deny death’s power leaves one a shadow or a wraith of their former selves, and in many ways accepting the inevitability of death with integrity is the only antidote to this enduring temptation. Some, however, still are able to take the journey west along the Straight Road out of the bent world and find the solace that world denies them.

Many critics since the 1950s have decried Tolkien as a reactionary who doesn’t belong in the pantheon of modern authors. But Tolkien is a quintessentially modern author insofar as he recognizes that certain construals of the world and certain answers to the question, “What are we to do?” which the pre-modern world offered are no longer adequate to the dilemmas of our time. So when champions of a parochial, comfortable version of modernity accused him of crafting diversionary, escapist fantasies fit only for children, he retorted (in the “On Fairy-Stories” essay) that,

I have claimed that Escape is one of the main functions of fairy-stories, and since I do not disapprove of them, it is plain that I do not accept the tone of scorn or pity with which “Escape” is now so often used: a tone for which the uses of the word outside literary criticism give no warrant at all. In what the misusers are fond of calling Real Life, Escape is evidently as a rule very practical, and may even be heroic. In real life it is difficult to blame it, unless it fails; in criticism it would seem to be the worse the better it succeeds. Evidently we are faced by a misuse of words, and also by a confusion of thought. Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls? The world outside has not become less real because the prisoner cannot see it. In using escape in this way the critics have chosen the wrong word, and, what is more, they are confusing, not always by sincere error, the Escape of the Prisoner with the Flight of the Deserter.

The longing for escape, in other words, just is the fitting response to some situations. It’s a false equivalence that treats the hope for something better as a dereliction of duty to the present. What good does it do for anyone’s soul to demand that they stay hunkered down in the mud and blood and shit of the trenches and look at nothing else? Or imagine anything else? What value do we think there is in a masochistic insistence on dwelling on the ruin and misery that characterize much of our experience in this world to the exclusion of anything better?

The technology that made the Great War’s bloodbath possible may seem comically antiquated now, but narratives of progress are as prevalent and vociferous as they’ve ever been. If you’ve been told you’re on the wrong side of history or have taken someone to task with that phrase, you are already acquainted with one contemporary version. The release of potential energy long brewed by the powers and principalities in that conflagration is still evident in the internecine conflict that characterizes life in the U.S. post-2016 just as much as it is in the cold wars and revolutions and genocides that typify the twentieth century.

It seems to me and to plenty of others that with his “escapist” fantasies Tolkien was actually tackling head-on the evils of the world and the need for courage to resist it. “Realist” fiction might scoff but by the same token its bourgeois characters typically had comparatively tinier, more civil monsters to face. This isn’t to belittle in any way the “smaller” trials we all endure that a Forster or a Wharton might chronicle — it’s a critique of the supercilious view that only the naturalist style is legitimate for encapsulating the struggle to live well. Moreover, hewing too closely to this style ignores the worldwide dimension of that struggle. Tolkien survived the horrendous death of one myth but lived to witness the proliferation of other, related myths spreading over Europe: Bolshevism, Nazism, fascism, unchecked technocracy, ecological apathy and devastation. Hope abhors a vacuum, and the elimination of one pernicious myth only demands the emergence of a new one to take its place. Tolkien developed his mythology to stand in this gap and bolster the courage of the unremarkable millions holding tight in the Age of Anxiety.

Tolkien, after all, was the one who convinced the initially skeptical C. S. Lewis that “the story of Christ is simply a true myth: a myth working on us in the same way as the others, but with this tremendous difference: that it really happened.” What Tolkien and Lewis understood better than most apologists, however, is that the myth-come-true of the Incarnation is served best by supplemental myths that depict an alternative way of being in the world. Lewis never once thought that this precluded more didactic styles of discourse; he simply recognized that an exclusive diet of instruction would never be adequate for getting by, let alone flourishing. The imagination must be catechized by story to resist the enticement and the drudgery of the fallen world-system, and with his Middle-Earth mythos Tolkien hoped to rouse his audience out of their torpor in the same way Merry had rallied the hobbits of Bywater with the Horn of Rohan to overthrow Sarumann’s technocratic regime.

Now, look: I know this probably sounds like I’m building to a crescendo to issue a call to arms, but I’m not. But for crying out loud it is a call to wake up: “Awake, O sleeper, and arise from the dead, and Christ will shine on you” (Ephesians 5:14). What does gospel ministry look like in a world that is still wracked with the aftershocks of the death of Europe and its ministry of rational liberalism? What myths hold out a carrot for us? What pictures hold us captive? We, on the other side of two world wars, still dally with similar charms as enticed Tolkien’s and Golding’s generations though we are surrounded by the repercussions of the wars that eviscerated them. How do we resist their enchantments? And must we insist on spurning all dreams of escape?

Of course the Christian hope can be recast as a Gnostic pie-in-the-sky denial of what is so wrong with the world, but that simply cannot mean we should stop envisioning the end of our suffering or drown all visions of a mended world (to use Tom Bombadil’s phrase). There is still a straight road out of this mess, and we don’t have to build it, thank God. But we can dream of it and of the renewed world it invites us to, and that can empower us to live well, today. In time, the Christ will embark on that straight road and make the bent world and all within it new. May that renew our courage and our compassion here and now.

COMMENTS

13 responses to “The Straight Road Out of a Buried World”

Leave a Reply

What an excellent post, Ian!

I am currently reading a biography of the English ‘war poet’ Wilfred Owen. He, too, lived in that era where ‘progress’ was always advancing. And it is amazing to see how his poetry changed, as the war went on; it was rather dreamy, in the years immediately preceding the war.

And then–when he joined the British Army, and witnessed the death and destruction all around, Owen changed. His immortal war poems became almost bitter. I think his fellow war poet Siegfried Sassoon had something to do with that.

Then Owen was killed in action, just a week before the Armistice. His family received news of his death, as the church bells rang, bands played, and the townspeople rejoiced. Talk about irony.

The Great War still has so many repercussions, even a century on. And there is a personal side to it, for me: my mother was born in Germany in 1917, when the war was starting to go badly for her fellow countrymen. It is a miracle, that she and her family survived the famine, disease, and hard times that followed the Armistice. She and her immediate family emigrated to the US in 1923: just ten years before the Nazis came to power.

If my mother had died in early infancy–my sisters and I wouldn’t have been born!

Thanks again, for this excellent post, Ian.

Thanks very much, Patricia! I am very grateful your mom and her family made it out of there, and the enormity of that shows up the millions of contingencies that go into these massive, epoch-defining things like WWI. It’s easy to lose sight of the humanity of something so huge and easy to forget that even those who make it out alive lose something.

Great piece. It left me somber and disturbed in a good way. Thanks so much for a timely and well written and much needed rethinking of my energy.

Thank you, Sam! That’s about exactly what I was aiming for, I’m glad it struck home. I think we’re all in need of a good rethinking and a prodding towards what I think is the 20th century’s most profound literary reflection on the nature of evil will only help.

Ian, this is marvelous!

I’ve never quite been able to put my finger on why most post-WWI/WW2 musings on hope & future have never completely sat right with me. Now, I think it’s because they actually buy into the kind of problematic myth you describe here–but of course, with a more heroic [or perhaps marginally less monstrous] sheen. But that’s simply trading the devil for the witch; it’s still trying to propagate the myth of political self-sufficiency but with a union jack or the stars & stripes (instead of decidedly less palatable symbols). But none of these are sufficient to break away from the prison of strife & death. I’m not sure even the best of these lesser myths is worth some of the more recent sacrifices that we have offered.

True Myth, however, is the one thing that makes all else worth fighting for.

Thank you – if we are to imagine Sisyphus happy, I think we must also imagine that he fills his mental life with thoughts of a world free of stones and hills…

I will say only (at this time) how grateful I am that Ian is my son.

Great post Ian. Thanks. Have you read Laconte’s book “A Hobbit, A Wardrobe and A Great War”?

No, I have not! But now I may have to track it down. I plan on reading a lot of Tolkien and Lewis this winter, and I think it might be for the best if we all did, as I can’t think of another pair of writers who bolster my courage as much as those two and I think they could do the same for anyone.

Ian! Love your post. I want to cite you. What the heck is your last name?!

Olson! (Minus the exclamation point)

Thanks!