“It’s not quite reality. It’s like a totally filtered reality. It’s like you can pretend everything’s not quite the way it is.” – Joshua Leonard

1. Envy: according to Moya Sarner at The Guardian this deadly sin is more present in our everyday lives than ever before, thanks to social media. More than a mere tug of longing, envy is the resentment of seeing what another person has, and wanting to take it from them. This is certainly not the first time this site has mentioned the despair of social media, but Sarner’s observations are too sharp to tune out.

She writes that not only do we compare ourselves to friends and neighbors (as people have always done), but now, online, we measure up against people all over the globe, celebrities and strangers, friends of friends. Windy Dryden, a cognitive behavioral therapist, has coined this “comparisonitis,” an emotional sickness which can’t be intellectualized or curbed by willpower. We know we’re seeing “a totally filtered reality,” but knowledge and intellectualization—telling ourselves we need not compare—cannot help us here. The feelings are too powerful.

“Ingrid Goes West.” Matt Spicer

Furthermore, Sarner writes, “No age group or social class is immune from envy.” Thus the impressionable young people everyone seems so worried about are as susceptible to extreme envy as their parents, and grandparents, teachers and others. Social psychologist Sherry Turkle makes a poignant observation:

We look at the lives we have constructed online in which we only show the best of ourselves, and we feel a fear of missing out in relation to our own lives. We don’t measure up to the lives we tell others we are living, and we look at the self as though it were an other, and feel envious of it.

Sarner concludes with what may well be the year’s most apt translation of the “whitewashed tombs” verse: “While we are busy finding the perfect camera angle, our lives become a dazzling, flawless carapace, empty inside but for the envy of others and ourselves.” It’s not the only spiritual tension here. Dryden says that when it comes to the thing you envy, “you can survive without it, and that not having it does not make you less worthy or less of a person.” This is when religion, Christianity in particular, becomes truly impactful, conveying that our worth is not in what we have or can achieve but in something deeper, less fleeting.

Just as hunger tells us we need to eat, the feeling of envy, if we can listen to it in the right way, could show us what is missing from our lives that really matters to us, Kross explains. Andrew says: “It is about naming it as an emotion, knowing how it feels, and then not interpreting it as a positive or a negative, but trying to understand what it is telling you that you want. If that is achievable, you could take proper steps towards achieving it. But at the same time, ask yourself, what would be good enough?”

[Now seems like a good time to mention, The New Yorker made a funny with their New Social-Media User Guidelines: “From now on, all LinkedIn users must occasionally use LinkedIn.” HA. h/t MP]

2. I really liked this excerpt from Heather Havrilesky’s new book, What If This Were Enough? A monologue of quiet rage, this will certainly make different impressions on different people, but one thing is sure: it crackles. HH vividly illustrates the suffocation of the little-l laws which sprinkle adulthood, particularly among seemingly stable adults who perhaps experienced some ‘hard times’ in the past but have now overcome all visible strife, thank God:

Penguin Random House LLC

Let’s be honest, some days, sensible middle-aged urban liberal adult professionals are the most tedious people in the world. I know that I should feel grateful that these people, my peers, are enlightened, that they listen to NPR and read The Atlantic… I should be thankful that almost everyone at this party skimmed The New York Times this morning. I should feel glad that they read the latest book by Donna Tartt so they can tell me that they didn’t think it was all that good, in the vaguest terms possible. I should see this as an opportunity to hear myself say words…but without insulting anyone or swearing for no reason or making spit fly out of my mouth in the process. But I might get long-winded and say too much. There is a palpable pressure to never say too much here. There is an imaginary egg timer for every comment. The sand runs out, the eyes go dead…

I can’t do it. The quiet restraint, the lack of discernible needs or desires, the undifferentiated sea of dry-cleaned nothingness, the small sips, the half smiles, the polite pauses, the autopilot nodding. It feels like we’re all voluntarily erasing ourselves, as if that’s the only appropriate thing to do.

So I sit in the backyard, on the grass, alone, away from the adults. I think about what it means to blend into the scenery until you disappear. I wonder why that’s the point.

Havrilesky starts playing fetch with a stinky, aggressive dog and figures, “The dog is never quite satisfied. I feel good. This is much better.”

It’s not that any of the things she mentions (Donna Tartt, polite conversation) are bad: but overwhelming shoulds and apparent goodness get stale overtime. Not just boring but insufferable, in my experience, in a world mad with disease and dissonance. Boring parties may be one way of coping, but I’m with Heather, you’ll find me out back with the dogs.

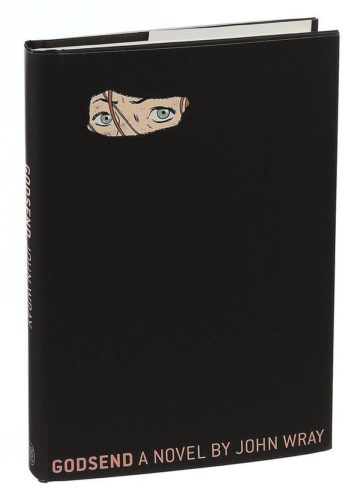

3. Godsend by John Wray: is a novel I want to read! James Wood gave it a positive review, calling it “the 9/11 novel that finally understands the fulfillments of faith.” Since 2001, Wood says, novelists have tried and failed to capture the impossibly complex quandary of faith-based violence. This novel apparently succeeds by approaching the subject with genuine sympathy. It’s the story of a fiery young American girl who converts to Islam, travels to Pakistan, and finds herself in the company of militant Islamists.

Sonny Figueroa/The New York Times

If American novelists in recent years have struggled to dramatize convincingly the dynamics of Islamic belief (and unwavering religious commitment generally), it is perhaps because submission is nowadays an alien and suspect category of experience. […]

[Wray bypasses] the hysteria of inquiry, the dunning “Why?” that tends to dominate in cases of Western converts to Islam. When someone like Aden Sawyer does what she does, our hunger for motive is mortally unappeased, as if we were analyzing a suicide. Our anxiety around the question of “radicalization” is, in part, an anxiety around the insufficiency of our explanations. Wray’s novel acknowledges what is inexplicable and mysterious, but it grounds what can be known about Aden’s motivations in her need for religious satiety, rather than in any obviously radical desire for violent extremism.

… [Aden] recalls visiting, back home with her father, “a little ugly mosque in a storefront.” Her father dismissed the place, and scoffed that the worshippers barely knew their prayers. But Aden returned there, without telling him: “I kept it a secret. I went every day for a month. Then I met my friend Decker. And then I felt full.”

The allure of “fullness” offered by religion compels something very deep within us. It has the power to take us far beyond the edges of rationality: to, for example, spend hours scrolling enviously on social media, as mentioned above.

Not having read the book, I do get the sense that Aden seems motivated by rebellion as much as by a genuine spiritual craving. One man’s secular humanism is another girl’s oppressive regime. To be sure, people have for centuries found fulfillment in submission, as awful as it sounds to modern ears: letting go, conceding to the way of a higher being, and becoming a small piece of a larger, embedded tradition, history, and community. Powerful motivators indeed.

4. Social science for the week: yet another a study shows the power of bias to prevent people from seeing personal issues objectively. It’s called “my-side bias”: a common prejudice suggesting people can be “highly motivated to protect their existing views.” Similar to confirmation bias, my-side bias occurs when, without realizing it, people bend logic to defend political/religious views:

…this “my-side bias” was actually greater among participants with prior experience or training in logic (the researchers aren’t sure why, but perhaps prior training in logic gave participants even greater confidence to accept syllogisms that supported their current views — whatever the reason, it shows again what a challenge it is for people to think objectively). […]

“Our values can blind us to acknowledging the same logic in our opponent’s arguments if the values underlying these arguments offend our own.”

Broadly speaking, it seems that values are, well, valuable. Detached objectivity remains unmatched, if even attainable, against deeply entrenched convictions. Related: “Hiding in Plain Sight: The Lost Doctrine of Sin.”

5. For a recent issue of John Hopkins Magazine, Tim Krieder contributed a beautiful personal reflection on what is called the “persistence of vision” — the experience of seeing life through multiple lenses, what was and what is:

I sometimes resent that old friends continue to see me as I was years ago, and not as the person I like to think I’ve become. Some of them still see the collegiate goofball with an affectation for Hawaiian shirts as my true identity… I have to beg Annie not to tell the story again about how I showed up at a chic SoHo restaurant where she was taking me out for my birthday completely blacked out…not just because it was a boorish thing to do but because I want to believe, and impress upon everyone, that that story is not about me anymore.

Those obsolescent perceptions feel stifling when you’re trying to change while your friends are exerting subtle pressure on you to remain the same… There’s some deep conservatism at work here, a denial of age and change. (Maybe this is why child stars so seldom manage the transition to adult careers; even if they turn out to be perfectly attractive adults, they still seem like grotesque caricatures of their iconic childhood selves, as if disfigured by age.)

It’s especially infuriating when our families insist on seeing us as children, as though we were still, in middle age, in need of instruction in matters like ordering in restaurants or stopping at stop signs. Which is why lots of people instantly revert to surly teens around their parents. You see people react with insanely disproportionate resentment at seemingly innocuous remarks made by siblings or spouses; they’re really reacting to the million previous remarks that all insinuated exactly the same thing. It took my mother decades to suppress the reflex to fling a protective arm across me whenever I’m in the passenger seat of a car and she has to brake, as if I were someone whose trajectory she could still hope to interrupt.

The above descriptions remind me of what my born-again college friends used to say before summer break: “Remember, it’s hard to be holy at home.” It was. The new life I had begun at college seemed uncomfortably old the moment I walked through my parents’ front door. Krieder, eventually musing on eternity, reminds me that the craft of identity is and never has been within my power.

6. A surprisingly poignant piece from The Cut: “Dating without texting is the absolute best,” by Clara Artschwager. Describing an experiment that seems fit for a 2018 episode of Seinfeld, Clara embarks on a relationship where texting is off-limits. She then discovers the power of romantic longing and the importance of uncommunication, i.e. not trying to control or map out every little thing in her romantic partner’s life. She further experiences the relief of not having to worry about the myriad interpretations of punctuation marks and emojis, and their absence.

Anticipation took anxiety’s place: I was excited to tell him about all the things I was reading, seeing, and doing. I had so many questions for him: How was his week? How was his writing? What did he eat? What was he reading? There was so much to talk about.

The less we were in touch, the better it was once we were together. Conversation poured out of us as if we had been turned upside down. We could barely keep up, often having to go back to complete a thought before jumping to the next subject. But most importantly, I could miss him. And doing so helped me understand how I felt about this person, something that had been clouded by all the superfluous, though sweet, communication in the past.

Strays:

- Friend/former conference speaker Alan Jacobs shares some extremely spoilery thoughts on Better Call Saul!

- For The Wall Street Journal, Julie Jargon details the Great Coffee Wars among office-workers in America (ht MM). #lowanthropology

- Cheers to all at the OKC Conference!

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Another Week Ends: Comparisonitis, Funk Apostles, Boring Adults, Coffee Wars, Religious Radicalization, and the Ageless Persistence of Vision”

Leave a Reply

Awesome recount, CJ. Really good stuff. I especially love the HH excerpt~

“I can’t do it. The quiet restraint, the lack of discernible needs or desires, the undifferentiated sea of dry-cleaned nothingness, the small sips, the half smiles, the polite pauses, the autopilot nodding. It feels like we’re all voluntarily erasing ourselves, as if that’s the only appropriate thing to do.”