Mike Spackman’s voice broke a little as he described the experience of being awarded 2017’s Cook of the Year at the BBC’s Food and Farming Awards. He said when The Naked Chef himself, Jamie Oliver, announced his name, it was like that scene from Babe, where Farmer Hoggett says, “That’ll do pig, that’ll do.” His Britishness made those tears somehow even more poignant. Shelia Dillon, the host of BBC 4’s The Food Programme, and one of the judges, described the Awards like this:

This, we believe, is the one moment in the year when Britain comes together to celebrate the country’s unheralded heroes. People who aren’t driven first by fame or money, but by a love of what they do and a belief in the outside chance they might actually make a difference.

Featured in nearly every episode of The Food Programme (a favorite podcast, by the way, of Krista Tippett, host of On Being) these “unheralded heroes” serve as examples of stewards, who as part of their stewardship mentor others, knowing food can be a gateway to health and independence, financial and otherwise. For people like Mike Spackman, The Community Chef who teaches and serves at-risk groups in his local area, the recognition he received is a real Martin Buber I/Thou type of moment. We often feel like anonymous objects in today’s world, so to be noticed and affirmed is a very real expression of grace.

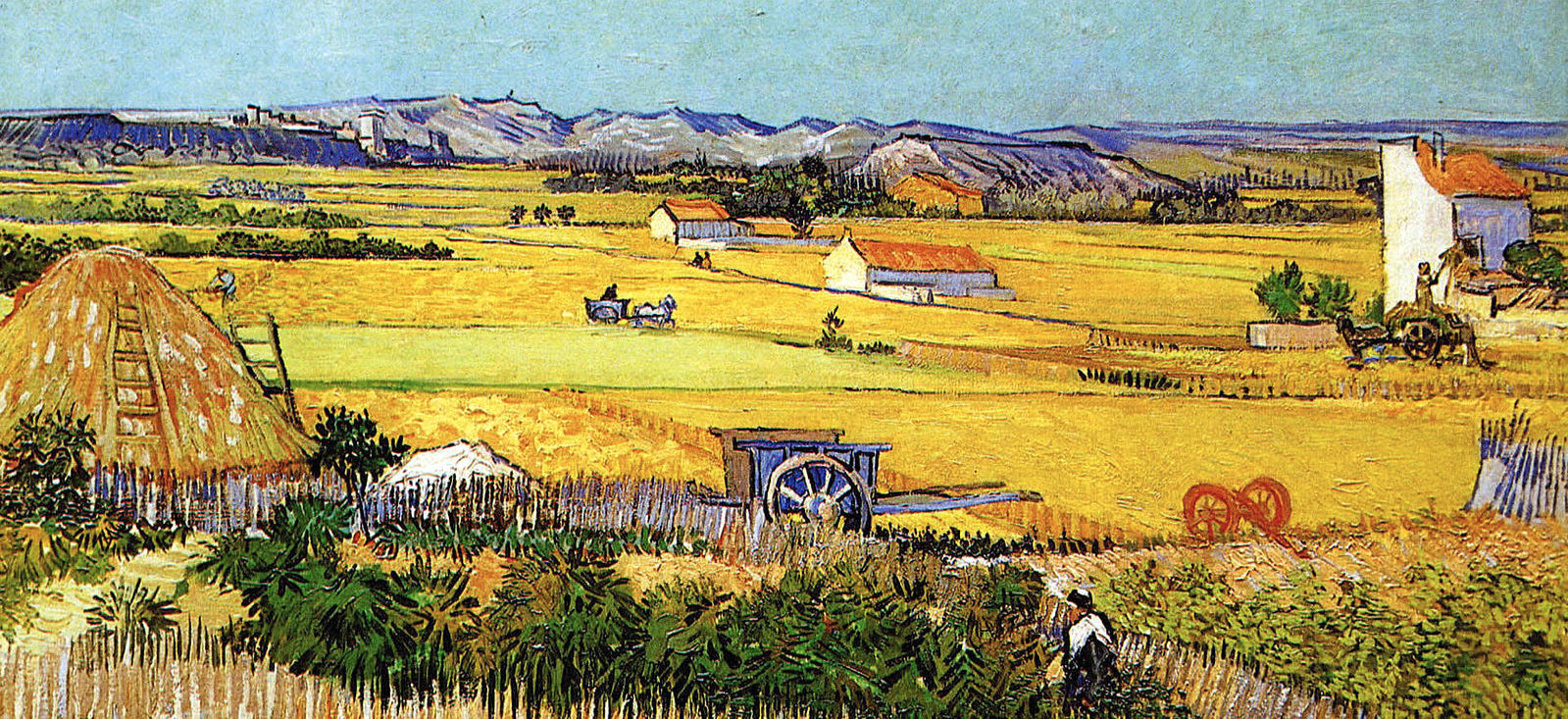

I’m not a farmer or a son of a farmer, but I was raised to respect those who make their living from the land. Living in a rural area like I do, you see agriculture is not for the faint of heart. Those engaged in more sustainable forms of the industry find that adding the “road less traveled” element often shrinks their community even more. Dismissed as naive, idealistic hippies, the truth is, once they submit themselves to the vagaries and increasingly unpredictable moods of nature, the naive part gets beat out of them rather quickly. They’ve also learned that they need help from those who have traveled this road before them. Mentoring becomes a vital element, not only of their continuing education, but to their survival. Stewardship and mentoring are intertwined in my mind, as I’ve written about before. We see it in 1 John 4:9, “We love because He first loved us.” We steward what we value, and that stewardship is in response to the grace that has been shown to us. It’s a reaction, not a task.

In the Church, discipleship, mentoring, and spiritual direction have become a bit of a lost art. Having been mentored and having mentored a bit myself, I found that there were few resources to draw from. Oh, I have stacks of books on the subject, piled into rather impressively leaning towers, but they all tend to describe something different than what I have experienced in real life. The examples, to state it rather bluntly, are a bit thin on the ground. I say all that because when I’ve tried to encourage discipleship, particularly inter-generational discipleship and mentoring in a couple of different church contexts, there was such an allergy to the idea — staying with the metaphor — one would have thought by the reaction it prompted, that I had shoved a fistful of ragweed into their faces, shouting, “Smell it, smell it!”

It soon became obvious I needed to look further afield for examples. I did find them, but in some rather unlikely places.

Joel Salatin of Polyface Farms, a self-described “Christian-conservative-libertarian-environmentalist-lunatic farmer,” to quote from Michael Pollan’s book, The Omnivore’s Dilemma, is a well known mover and shaker in the sustainable food movement. There is a great little scene in Pollan’s book where he describes a meal in the Salatin household:

Joel began the meal by closing his eyes and saying a rambling and strikingly non-generic version of grace, offering a fairly detailed summary of the day’s doings to a Lord who, to judge by Joel’s tone of easy familiarity, was present and keenly interested.

Joel recently wrote a book called Fields of Farmers, Interning, Mentoring, Partnering, Germinating, to address a very specific need. Farmers are aging, and their children are often not continuing in the same profession. With the average age of a farmer being 60, in the next couple of decades nearly 50 percent of their land will change hands, much of which will not remain in active farming, it is becoming clear we are facing a crisis. Salatin believes mentoring is a way not only to educate those interested in farming as a profession, but also as a way to address the crisis, by connecting the farmers who have the land with the experienced people-power needed to work it. Polyface’s vibrant intern program is proof of concept, with hundreds applying each year, and by Salatin’s own description of them in his book, you can see why it’s successful:

Today’s interns are tomorrow’s farmers, the foundation for vibrant rural economies. I’ll love them, care for them, encourage them, teach them, springboard them wherever they want to go. Every country in the world would be better if its fields were stewarded by the kind of young people who come through our intern program. They are the most enjoyable, fun-loving, hard-working, conscientious young people you could ever imagine.

Salatin illustrates with stories and examples from his own experiences throughout the book, never shying away from challenging conventional wisdom if that convention is counterproductive. Everything worth doing is worth examination and reflection. This also bleeds through into his philosophy of mentoring:

Showing isn’t enough. Teaching isn’t enough. Working together isn’t enough. Pay isn’t enough. Mentorship requires something more. It requires an emotional investment. It means getting down and dirty with relationships.

That sure sounds a lot like discipleship to me! I reached out to Joel to ask him what gave him both hope as well as heartburn about this current generation. While you may or may not agree with his assessment, I do want you to pay particular attention to how he approaches the topic:

Today’s young generation has three assets that when inverted, create big liabilities. Here they are:

CARE. Young people today care far more for more about important things than my generation did or does.They care about the environment, about animal welfare, about human respect, nutrition, and soil. That’s a good thing. The downside of this is an assumption that because they care, they’re entitled to paychecks and perks. This generates a lackadaisical business sense. Caring does not guarantee nor entitle anyone to profitability or opportunity: you still have to make your way.

COMMUNITY. The rugged individualist of yesteryear has given way to a sense of village, relationship, and the power of networking and collaboration. Young people embrace team building and the notion that one plus one equals three. The downside is that shallowness rules the day. Community used to be familial and geographic; today it’s Twitter, Facebook, global and quick. None of this engenders depth; it’s short conversations and frenzied friends.

CONVENIENCE. Efficiency and concentrating on greatest marginal reaction are great attributes among young people. Innovating easier and more productive ways of doing things are now possible at warp speed with computer design and distribution software. The downside is flitting from one thing to another and inability to grasp the slog that’s necessary for success. Failure to receive a “like” every 30 minutes results in depression. Failure to get a job promotion within six months means “nobody likes me here.” Mastery requires experience, and you can’t Google experience.

This struck me as an example of grace in reality, or to put it another way, a proper estimation of oneself. Joel shares that low anthropology we talk about, but he doesn’t approach it in a “kids these days” manner. You cannot mentor or disciple purely through misguided flattery or by constant misanthropic critique. Law and gospel serves as a healthy disillusionment, to use the word rather literally; a removal of a lie so, ideally, the truth can replace it. Our friend Scott Jones says it like this:

People are addicted to narratives that are comfortable and not always true.

Existing in a false narrative, self-generated or not, is a recipe for disaster. The real story about ourselves looks a lot more like how the Rev. Jacob Smith describes it:

We are all three bad days in a row away from becoming a tabloid headline, and most of us are already on day two.

This came to mind when I was listening to Chris Blanchard’s Farmer to Farmer Podcast interview with Frank Morton, proprietor of Wild Garden Seeds. There was something towards the end of their conversation that stood out when Frank said:

I know too much to think that I could get a better outcome by changing a few things 20 years ago.

That sounds an awful lot like a realistic estimation of not only himself but the world around him — an estimation that can only can come from real life experience.

I need to pause here a moment.

Frank is a farmer who specializes in lettuce breeding. After listening to the interview, I was so taken by his comment above that I sent him an email asking him to flesh that out a bit. Immediately after clicking “send,” I literally smacked my forehead; why in the world would I ask a farmer, in the middle of the busiest time of his year to sit down and write something for a perfect stranger? As a testimony to his graciousness, he replied the very next day. Here is what he sent:

What I probably meant in that moment, which you have to realize was just spontaneous stream of consciousness, is that I know too well that plans and intentions are ephemeral things. The weather is all it takes to upend the best laid plans, as the man ‘splained it so long ago. And then there are the plans of others, seldom synchronized with our own. Between the weather and the actions of others, little is certain and nothing can be predicted. Changing one thing about my methods or habits may create a change in the future outcomes, but the causality will most certainly be lost in all the normal chaos of living. Chaos is a normal thing when there are three or more variables…have 3 children if you don’t believe me. If I was a different person in one small way 30 years ago, no one can say what truth or consequences I would enjoy today.

Life is uneven. The weather is never on the calendar. After a life farming soil outside in partnership with a lot of helpers, I say plans are fine as long as you don’t expect too much of them. Plan to do what you have to do.

Franks’s practical example of humility in the face of the realization of how little we are in control of our lives reminds me of a passage from a recently translated collection of stories titled Cross Roads, by the early 20th century Czech writer Karel Capek:

It’s not possible to search for God using the methods of a detective… There is no way. You can only wait till God’s axe severs your roots: then you will understand that you are here only through a miracle, and you will remain fixed forever in wonderment and equilibrium.

It seems we all, the church included, could learn a lot about grace in discipleship and mentoring from people like Mike Sprackman, Joel Salatin, and Frank Morton, and the other men and women engaged in the task of stewarding the soil. They demonstrate it not only in their lives and interactions, but also by how they make their very living. I think their stories really do describe that wonderment and equilibrium Capek talks about. I also think, they, along with the rest of us, long to hear the words, like Mike Spackman did: “Well done, good and faithful servant,” or to use Mike’s translation, “That’ll do pig, that’ll do.”

COMMENTS

One response to “Depth of Fields: Stewarding the Stewards of a Movement”

Leave a Reply

[…] Morton of Wild Garden Seeds, what it’s like running a seed company during the plague. We’ve heard from Frank before, and I always appreciate his wise and thoughtful answers to whatever out-of-the-blue question I […]