It’s hard to say exactly when the plummet of Elvis Presley began. Some say in the late 60s, some say the early 70s. Some might say as early as 1958, when he was drafted into the Army. In any case, there’s no denying the devilish phase of physical and mental deterioration that carried him to his death, at age 42, in 1977. The King’s final view of this world was the cold tile, probably, of his bathroom wall.

During the height of his career, Elvis seemed a different man, if even a man he was. I need not say much, since of course you already know. A musical phenomenon. A cultural revolutionary. His is the crème de la crème of success stories. Oh to be young Elvis—adored by all, chased day and night by flocks of fanatical young women, my grandmother among them. On some level, this is the life we all want. (You don’t want my grandmother chasing you?) (Yes you do…)

You may not be a fame seeker or aspiring musician, but maybe you are. In any case, there is a restlessness, in you, in me. We want our work to be recognized, heralded. Affirmation—adoration—this what many single people hope to find in marriage. It’s what many married people hope to find in their kids, or a career, in achievements or promotion.

In her latest collection of essays, Feel Free, Zadie Smith ruminates on the celebrity life, and the allure of it. In ‘Meet Justin Bieber!,” she wonders what the Biebs’ internal life might be like, emotionally, and spiritually:

…experiencing himself as the sole and obsessive focus of an unending line of teenagers. […] With a fixed smile on his face he listens as they say the magic words, over and over: “I can’t believe I’m meeting Justin Bieber!” As if he were not a person at all, but a mountain range they had just climbed. This is Justin Bieber, the “love object.”

The idea of the love object: this is what interests me. It’s a condition to which many people aspire, now more than ever. You can see why: so much love flows toward the love object. Why would we aspire to be doctors or teachers when we have before us the model of the love object? To walk into the world and meet love, from everyone, everywhere—this is a rational dream. By contrast, most of us enter the world and cannot be sure what we will meet: perhaps resistance, perhaps indifference, perhaps contempt. The moment of meeting is always unsure, fraught. But for the love object there is a smooth certainty to all encounters. This is because all meetings with others have in one sense already happened, for the love object is already known and loved everywhere. He meets only those who feel they have already met him, and already love him.

The dream of being known and loved by everyone you encounter; of being certain that you are wanted right where you are; to matter so much that you have to hide behind sunglasses every time you go outside… “This is a rational dream.”

All of this is a long-winded way of introducing Denis Johnson’s latest (and last) book, The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, which I’ve immensely enjoyed. It’s one I’ll return to time and again. In its five stories, ambition is everywhere but mainly through a backwards glance. Like Bieber and Elvis (and, to some extent, Johnson himself), many of the characters in Largesse are by and large successful—love objects in their own rights—and their stories are about whatever comes after success.

When it comes to accepting life as-is, to living within the limitations of the present moment, ambitious living may seem an alluring alternative. Johnson’s writing often testifies that, much of the time, being present sucks. Addiction and self-sabotage are frequent melodies played by his characters whose everyday lives are uncomfortable, and weird. Certainly, in any given moment, these characters may encounter mystery, wonder, and the sublime—but also, frequently, chaos and confusion. So for them, as for us, ambition is an antidote, the promise of a way out.

But what I really love about Johnson’s take on ambition is that it comes through fiction, which by nature is not a prescriptive medium. In the third story, “Triumph Over the Grave,” an acclaimed writer named Darcy describes how his book was adapted as a feature film:

Darcy…described for us the stages, a better word is paroxysms, by which his first novel had become a successful movie more than a decade after its publication. First the producers added years to the hero’s age and signed John Wayne; some weeks into the development process, however, John Wayne died. They dialed back the hero’s age and cast Rip Torn…but Rip Torn got arrested, not for the first time, or the last… Clint Eastwood liked it, and said so for nearly two years before negotiations hit a wall. In a fit of silliness, pure folly, the producers took an offer to Paul Newman. Newman accepted. The film was shot, cut, and distributed, and it did all right for everybody involved.

Darcy’s ambition in writing the novel, the producers’ ambition in casting the right actor, the actors’ ambition in getting the right part…all these rise and converge with a devastating(ly lighthearted) “it did all right.”

You get the sense that Johnson himself is somehow embodied, however abstractly, in his frenetic, idiosyncratic characters, many of whom are writers, and good ones. Like Darcy, Johnson was a National Book Award winner, a Pulitzer finalist. Darcy puts such acclaim in perspective: “Some of my peers believe I’m famous. Most of my peers have never heard of me. But it’s nice to think you have a skill, you can produce an effect.” A universal desire: to produce an effect, to tame the world, which does not in the end belong to us.

So much of the stories’ power resides in their meandering, however strangely, to their endings, at which point death is usually somehow accepted, or confronted. “Triumph Over the Grave” ultimately becomes the story of Darcy’s deterioration from a man of many triumphs to a man trapped in a body that eventually stops working. His isn’t the only one. Around him, acquaintances drop like flies. It might seem morose, even melodramatic, were it not for the brutal directness of it, which makes it all kind of funny. Johnson’s darkly humorous death-stare seems indicative of the way he might have approached his own death, which occurred in May 2017, before this book was published.

Short of reproducing the entire book, the best I can do is point to some its most electric lines, which often come in a concluding paragraph, such as here, once again from “Triumph Over the Grave”:

…after four or five years Mrs. Exroy and I stopped bumping into each other, because she died too. Oh—and just a few weeks ago in Marin County my friend Nan, Robert’s widow…took sick and passed away. It doesn’t matter. The world keeps turning. It’s plain to you that at the time I write this, I’m not dead. But maybe by the time you read it.

It may be the best concluding line I’ve ever read—at once abrupt and satisfying. True, it’s the narrator speaking, not the author, but Denis Johnson, the man, is in there somewhere, himself dead by the time you read it. Yet his words aren’t despairing or nihilistic. They’re just true. High road or low road, whether slaves to ambition or happiness, we are going to die, and the world as we know it will pass away. The people who nurse us in our sickness, they too will die. The music we make, the books we write—don’t go with us.

Like Elvis, many of Johnson’s characters arrive at the top of their respective ladders, and find their penthouse views lacking; still death comes. We see this with today’s celebrities as well. Elon Musk’s spiritual void has become a joke. And then there’s the memorable self-destructions of Lindsay Lohan and Britney Spears. Michael Jackson. Elvis Presley. Justin Bieber. In her essay on the ‘love object,’ Zadie Smith investigates this seemingly guaranteed bankruptcy:

And yet—having watched this process so many times—we, the public, know perfectly well that the love object is, more often than not, a tragic figure. The love object “lives the dream” (the dream that everybody you meet says: “I love you!”) until this dream becomes a nightmare. Then the moment arrives when the love object himself no longer wants to meet anyone…

The love object withdraws. He is rarely seen in public and when he is, strange things happen. What meetings he does have all seem to go awry: people get punched, phones are stolen, babies are dangled out of windows, drugs taken, cars crashed. His closest advisors begin to fear for him. He is urged into many new and alarming kinds of meetings, with therapists, drug counselors, nutritionists, accountants. But these meetings seem only to compound the problem: once again he is a kind of object to be analyzed tweaked, examined. His advisors despair.

When we confuse love with admiration, people become products for consumption. In her piece, Smith includes this little detail from Bieber: “‘Anne was a great girl. Hopefully she would have been a Belieber,’ wrote Justin, in the guest book of the Anne Frank Museum.” Oof! She continues:

Like Bieber, we treasure our identities as individuals, and, like Bieber, work hard to differentiate ourselves. Like Bieber, we feel we are having relationships even if, much of the time, our relations with others seem to exist mainly in the stories we tell (to ourselves, to others). […]

So now I think again of a Belieber in the Justin Bieber signing queue. She is lining up for an experience, an experience which even as it is happening seems to be relegated to the past tense, as in: I just held his hand, he just hugged me, I just met Justin Bieber… Not only is this meeting always already a story, it only really exists as narrative… It’s obvious that a Belieber’s only relation with the globally famous Bieber is as a piece of narrative to be told and retold—to herself, to other people—and that Bieber himself, in his human reality, is barely involved, almost unnecessary. It’s easy to scorn the Belieber’s for this, and yet we may also recognize elements of a Belieber’s encounter with Justin Bieber in many of our own relations with perfectly unfamous people: with our sister-in-law or mother, with our friends or partners, with our colleagues, even with our own children. If we are honest with ourselves it is not often that we let these people “fill the firmament.” Most of the time they present themselves simply as objects in our way, as examples of something, as annoyances and arguments, as assets that in some sense belong to us, or as the cause of—and explanation for—various elements of our own identities.

If, for example, our ambition stems from a deep-seated desire to impress our parents, we minimize them to vessels that can (and must!) be replenished by us, implying that their need is to tell us good job. They are no longer their own people with dreams, nightmares, observations, and feelings.

The twist is, when we operate as if people are objects, we eventually see ourselves in the same light: “Everything is an object,” Smith writes, “up to an including the self. As Buber has it [yes, Martin Buber]: [The love object] treats himself, too, as an It.” The end of ambition is the object-ification of everyone, ourselves included. A crazy-making loneliness ensues.

Smith, via Buber, says that the antidote is in being truly known; in being seen as person, as a ‘Thou,’ not an ‘It.’ If only we could understand that ‘other people’ are both entirely other and entirely people, that there is something mysterious about them, places they have seen that we never will, thoughts we will never hear, emotions we will never feel. Smith quotes Buber here:

When I confront a human being as my Thou and speak the basic word I-Thou to him, then he is no thing among things nor does he consist of things. He is no longer He or She, a dot in the world grid of space and time, nor a condition to be experienced and described, a loose bundle of named qualities. Neighborless and seamless, he is Thou and fills the firmament. Not as if there were nothing but he; but everything else lives in his light.

Of course we fail to see each other this way, but this is how the Christian God is believed to see his children. He doesn’t cheer from the sidelines, doesn’t wait outside the concert venue for a signature, and a hug, and a handshake. He doesn’t praise accomplishments and good deeds, except for that of his Son. To God, everything ‘lives in our light.’ We, apart from whatever we do, are valuable.

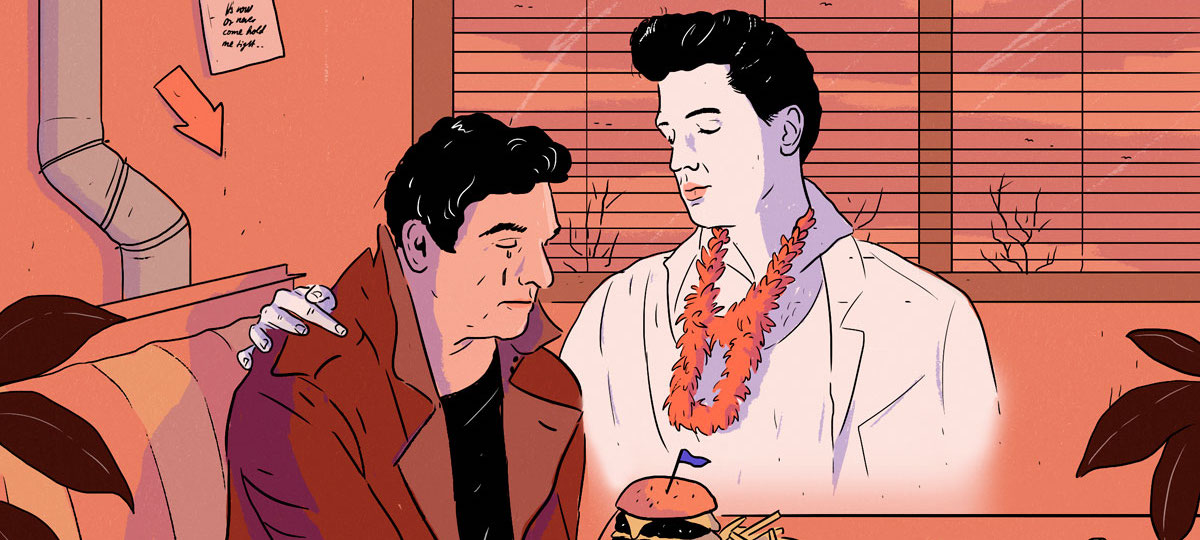

If his fiction is any indication, and I think it is, Denis Johnson understood this. His final story tunnels along these lines—ambition, approval, and the hope of something beyond all of that. “Doppelgänger, Poltergeist,” tells the story of Marcus Ahearn, a renowned poet who is obsessed with Elvis. Marcus is convinced that Elvis was murdered in 1958, and that his evil twin brother took his place, thereby explaining the marked shift in the King’s latter-days.

The King is a profound symbol for a man who, by his ambition, would be God but fails and falls embarrassingly short. Elvis is precisely the love object Zadie is talking about. Of course, Elvis the man is now synonymous with Elvis the ghost—the ghostly figure who lives on, in legacy, in spirit. The man who lives forever. He is not just a symbol for worldly success but for the afterlife.

Johnson’s character, conspiracy-theorist Marcus Ahearn, is also a love object, unbeknownst to him: an award-winning poet, the object of many a reader’s affection. The narrator says:

When he was my student, I told Marcus Ahearn he wrote wonderfully. He said it wasn’t the most important thing he did.

I wonder if that isn’t the secret of his greatness…

Our country’s finest poet, Marcus Ahearn, hasn’t published a poem in fifteen years, not a single line of verse. Two days ago, on Elvis’s birthday, the Memphis police arrested him at Graceland.

On that day, Marcus was digging up Elvis’s grave. He was on a quest to prove the 1977 death a sham; he believes the ghost of Elvis was seen walking around Paradise, Texas in 1958.

I answered instantly, pointing out that in order to accept this proof that Elvis was in Paradise in 1958, we first have to accept life after death, Paradise, ghosts, all of that.

Mark answered a couple of days later, I smile and shrug. Life after death, ghosts, Paradise, eternity—of course I take all of that as granted. Otherwise, where’s the fun?

Denis Johnson’s final published words are “Elvisly Yours.” With four silly syllables, all the mysterious, meandering roads come together: Elvis Presley, Marcus Ahearn, Denis Johnson, their lives, their deaths, their afterlives.

Critic James McManus once wrote that Denis Johnson “uncannily expresses both Christlike and pathological traits of mind.” The Largesse of the Sea Maiden continues in that vein, simultaneously sharing a frenzied restlessness and a transcendent peace.

It’s in Johnson’s directness in the face of death that his hope is communicated most powerfully—in the hope of something else, of some other time and place, where we are known fully, when we are released from the ‘it’ and are known in our full being, not admired but loved.

Stray observations:

- Really, only 3/5 stories deal with ambition. The other 2, “Starlight on Idaho,” and “Strangler Bob,” take an inverse tack as the characters approach mortality via utter failure.

- “Starlight on Idaho” deserves its own review, which I’d like to write at some point. It’s the conversion story of an addict. In rehab, the unhinged Mark Cassandra writes letters to everyone—to family members, to the Pope, to the Devil—and signs off his last one, “Your brother in Christ.”

COMMENTS

5 responses to “Peace/Love/Elvis: The Death of Ambition, and Also of Denis Johnson”

Leave a Reply

Thanks, CJ. 🙂

SO GOOD. And I absolutely want your grandmother chasing me ???????? made me lol

Love it! https://twitter.com/Justin_Buber/status/401018548836777984

Triumph Over the Grave is the fourth story, not the third.

noted thanks!