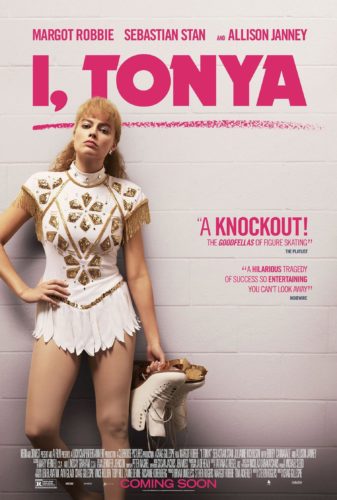

Where were you in 1994 when Nancy Kerrigan took the famous billy club to the knee? Can you believe that event took place nearly a quarter century ago? It’s one of those strange decade-defining events that’s lasted in our minds alongside the Milli Vanilli lip syncing scandal of 1990, the Clinton affair scandal of 1998, or the O.J. Simpson trial of 1994. For those who weren’t following the illustrious world of ’90s U.S. figure skating, or for those who simply weren’t born yet, there’s a fresh chance to get in on the story with this year’s Oscar bait dark comedy I, Tonya.

Where were you in 1994 when Nancy Kerrigan took the famous billy club to the knee? Can you believe that event took place nearly a quarter century ago? It’s one of those strange decade-defining events that’s lasted in our minds alongside the Milli Vanilli lip syncing scandal of 1990, the Clinton affair scandal of 1998, or the O.J. Simpson trial of 1994. For those who weren’t following the illustrious world of ’90s U.S. figure skating, or for those who simply weren’t born yet, there’s a fresh chance to get in on the story with this year’s Oscar bait dark comedy I, Tonya.

The story itself is infamous: Tonya Harding and Nancy Kerrigan were rival U.S. figure skaters competing for a spot on the 1994 Lillehammer Winter Olympics delegation. In January of ’94, an assailant, later revealed to be connected to Tonya Harding’s ex-husband, attacked Kerrigan after practice, attempting to break her leg. There was jail time for many involved, and Harding was banned from all future U.S. ice skating events. I, Tonya begins with a disclaimer that it’s based on “irony-free, wildly contradictory” interviews with its real life subjects. The movie is equal parts sports biopic, tabloid scandal, faux-documentary, and a dash of endorsement for JD Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy. It’s a film of justification, as the key players assert their innocence of the events surrounding Harding’s career and Kerrigan’s assault.

It’s one of many ’90s tales that have returned to us in the late 2010s. We’ve recently had the opportunity to revisit the trail of that decade with The People v. OJ Simpson. Monica Lewinski has her own jaw dropping, heart rending TED talk. You can even find Fab Morvan, one half of Milli Vanilli, sharing his first-hand account of the pop groups fall from grace on The Moth radio hour. Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised. 18 years after the ’90s, these scandals have slipped from headline news and water coolers to the conflict free comforts of nostalgia. I.e., it’s safe for them to be reengaged again, and that’s doubly true for the transgressors.

The story of Nathan the prophet ends with the famous words “you are the man,” a word of accusation to King David in the midst of David’s self-righteous rage against a hypothetical lamb thief. It’s a story familiar in the general if not the specific: David was guilty of using his kingly power to murder a man and steal his wife. Nathan tells the story back to David with the names and circumstances changed, and David’s outrage at his own circumstances seals his fate. At minimum, it should serve as a cautionary tale for our call out culture of 2018. Did we also exploit a vulnerable Monica Lewinsky at age 22? Do we as a culture have any culpability in the overdose death of Fab Morvan’s Milli Vanilli partner, Rob Pilatus? Is it hypocritical to loathe Tonya Harding’s mother when we laughed at David Letterman’s top 10 list crafted at Tonya’s expense?

The answer is: probably. The human propensity to scapegoat and self-justify by throwing another under the bus is pretty well documented. How many times have we here at Mbird singled out individuals as negative examples to prove a point? The Bible’s verb for this is “to scoff,” to mock and deride as shameful. “He saved others,” they said, “but he can’t save himself! He’s the king of Israel! Let him come down now from the cross, and we will believe in him.” This to a naked Jesus in the midst of his execution, the difference being that he’ll have the last laugh a few days later. These public figures from the ’90s don’t get to have their final word for nearly a quarter century.

As I, Tonya ramps up to its dramatic final skating scene, viewers watch as Tonya prepares her stage cosmetics. The scene shows Tonya fighting back tears as she adds the foundation and blush, practicing her performance smile, and trying to hold it together among the media pressure and FBI investigation. As she applies the reds and pinks to her face, the heavy makeup makes her appear flayed, as if her skin has been peeled away to show the muscle and sinew underneath. Tonya has learned, through her abusive ex, mother, and the crowds, that a success on the ice will finally lead to love. And as she smiles through the heavy makeup, we recognize that performance-based love is killing her. We’re not sure if she is beautiful or ugly, majestic or macabre, or if the collective “we” are the ones responsible.

There’s a scene in Dante’s Inferno that gets to this point quickly. In Canto XXX, Dante is being escorted through the 8th circle of hell, meets two shades condemned for their falsehoods: a Florentine Counterfeiter named Adam and Sinon the Greek, the man who opened the door for the Trojan Horse. The two condemned sinners, punished to an eternity of poetically just pestilence and illnesses, begin to argue and fight as to which one of them was the greater sinner. As the two come to blows and quibble over the subject, ill, laying on the ground, pathetically wanting to be better than the other sinner, Dante is enthralled by the scene, a voyeur into Hell’s understated pettiness. Virgil chastises Dante, suggesting that such squabbles are shameful and not there for entertainment, and Dante’s enthusiasm quickly turns to shame. The two then move on into Hell’s ninth circle.

I, Tonya is a terrific diagnosis of the virtue signaling world that’s blossomed since the 1990s. It’s a chastisement from Virgil, an accusation from Nathan, and a sobering reminder that there is none righteous, no, not even one. And it’s a reminder that will continue to come through the years, when we watch tell-all documentaries from the point of view of the Duggar children, the audio documentary of Harambe the Gorilla from the mother’s point of view, or the Shia Labeouf Oscar-bait biopic. This is a genre that, thankfully, (regretfully?) will always have with us, until the Son of Man returns with his final word.

COMMENTS

4 responses to “I, Tonya Justifies the ’90s”

Leave a Reply

????

I definitely remember the ‘Kneegate’ scandal, before the 1994 Winter Olympics. And I confess that I was glad, when Tonya Harding didn’t win a medal.

ESPN did a documentary on the whole episode, called ‘The Price of Gold’, a couple of years ago. There were interview clips with Harding today. She was almost pathetic, in her own attempts at self-justification over the years. I ended up feeling very sad for her.

Excellent post, C.J.. Thank you.

OOPS. Sorry, Bryan J.. My bad. 🙁

A lot of disparate threads woven together masterfully, B. Thank you. “We’re not sure if she is beautiful or ugly, majestic or macabre, or if the collective “we” are the ones responsible.” Ain’t that the truth.