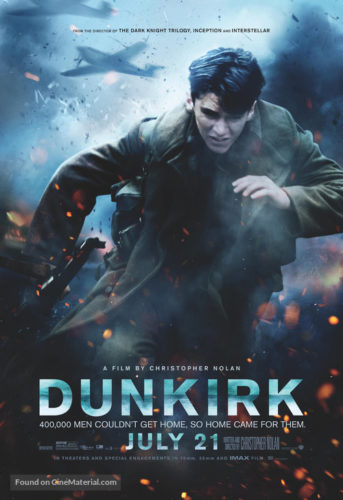

From May 27th to June 4th, 1940, the French port city of Dunkirk witnessed one of the most significant and history-altering military operations ever undertaken, the evacuation across the English Channel of nearly 400,000 British and French soldiers, right from under the teeth of the German army. You would know nearly nothing about it from watching Christopher Nolan’s Oscar-nominated Dunkirk, which is up for awards for best picture, best director, cinematography, production design, sound editing, and original score.

This is because Dunkirk isn’t really about the historical Dunkirk; it’s about Nolan’s artistic-cinematic vision. It’s a vision most critics raved about, rounding up the usual adjectives: epic, stunning, riveting, jaw-dropping, a triumph, terrifying, harrowing, a masterpiece, the-best-war-film-ever. Even the review in normally staid First Things gushed effusively that Nolan’s “superb new Dunkirk is a film for the ages. Riveting and beautifully acted, it is a war movie like no other, and may be the best of its kind.” Other Christian outlets have said similar things. There have been dissenters from this Nolan hagiography, most notably John Podhoretz in the US, and David Cox in the UK. And, of course, as you might have already suspected, this essay. But the consensus is certainly that Dunkirk is indeed a “film for the ages”, Nolan’s greatest masterpiece, and headed for Oscar gold.

This is because Dunkirk isn’t really about the historical Dunkirk; it’s about Nolan’s artistic-cinematic vision. It’s a vision most critics raved about, rounding up the usual adjectives: epic, stunning, riveting, jaw-dropping, a triumph, terrifying, harrowing, a masterpiece, the-best-war-film-ever. Even the review in normally staid First Things gushed effusively that Nolan’s “superb new Dunkirk is a film for the ages. Riveting and beautifully acted, it is a war movie like no other, and may be the best of its kind.” Other Christian outlets have said similar things. There have been dissenters from this Nolan hagiography, most notably John Podhoretz in the US, and David Cox in the UK. And, of course, as you might have already suspected, this essay. But the consensus is certainly that Dunkirk is indeed a “film for the ages”, Nolan’s greatest masterpiece, and headed for Oscar gold.

Dunkirk left me disappointed. I was looking for a well-told and true story—even a fictionalized narrative can tell the truth. What I saw was an auteur’s obsession. The cinematography is gorgeous, and the wide visual sweeps inspiring. But I found Nolan’s celebrated techniques—reliance on nonlinear narrative, minimalism in dialogue, lack of character development—to be off-putting. Neither the visual impact nor the foregrounding of technique and style can make up for what Podhoretz called Dunkirk’s “epic narrative fail.” We do not so much get a story as an “experience”, or rather an attempt to immerse the audience into the immediate experience of what happened at Dunkirk, as Nolan puts it: “We came upon the notion of creating a very experiential film, one that rather than trying to address the politics of the situation, the geopolitical situation, would really put you on the beach where 400,000 people are trapped, surrounded by the enemy closing in and faced with annihilation or surrender.”

So, in the interest of making the first virtual reality movie, Nolan decontextualized the historical events. The film’s opening title sequence features a few vague sentences on the screen, letting us know an unnamed “Enemy” surrounds an undefined army, threatening their annihilation. Kenneth Branagh’s character, a fictional Royal Navy Commander, occasionally gazes toward the camera and offers a few lines of on-the-nose commentary on the immediate situation. That’s it. Nolan isn’t kidding when he says he doesn’t address the “geopolitical situation.” No British, French, or German commander is mentioned by name. Hitler isn’t mentioned. Neither the word “Nazi” nor “German” are uttered. We never see a German soldier, until near the end when we get a glimpse of a small detachment that captures a British pilot. Winston Churchill is mentioned only fleetingly, at the very end of the movie. This washing out of history from Dunkirk extends from the strategic down to the tactical, so to speak. From Nolan’s account, you would think the Royal Air Force consisted of three Spitfires, and the German Luftwaffe of three Messerschmitt fighters, a couple of Stuka dive-bombers, and one Heinkel high-level bomber. What actually happened was that the RAF flew thousands of sorties (a sortie = one plane flying one mission) over Dunkirk, while the usual Luftwaffe raid could include up to forty Stukas or several high-level bombers, along with fighter escorts. The Royal Navy sent dozens of destroyers and hundreds of smaller vessels to Dunkirk, not the paltry few we see in the movie.

Nolan doesn’t stop with neglecting history in his pursuit of placing his audience within a simulation of reality; he neglects character development as well. Most of the main characters in Dunkirk are as flat as the cardboard cutouts Nolan used, in lieu of CGI, to depict masses of soldiers on the beach. With little dialogue, and no backstories—not even names—we are left to decipher in only a few minutes who these men are—what they feel, what they fear, their hopes, their longings—solely by their actions. This is difficult enough in real life. In the contrived space and time of movie make-believe, it is impossible. Nolan seems to believe that by attenuating the personal character of the primary protagonists, we can more easily immerse ourselves in their “harrowing” experience.

It did not work. All movies are make-believe, of course, but Nolan’s staging of the violence of modern war particularly stands out as contrived. His expressed desire to “achieve intensity” without being concerned with the “bloody aspects of combat” results in a shadow play of military conflict. The fairly recent cinematic convention for war films presenting a realistic verisimilitude of battle violence can be pushed beyond artistic necessity (as perhaps David Ayer did in Fury), but Nolan swings the pendulum to the opposite extreme. Fleeing soldiers are downed by automatic weapons fire, bombs explode among massed troops, Stukas reduce British ships to burning hulks, and torpedoes rip through men packed below decks, all without one shattered body, one visible wound, or even one drop of blood. The only blood we ever see is from the implausible head wound suffered by a young boy—George, the only character named in the movie—who is sailing aboard one of the civilian “little ships” that helped evacuate Dunkirk.

I can believe it when Nolan tells us, “Dunkirk is not a war film.” But neither is it the “survival story” he says it is. Or rather, I would say Dunkirk failed to make me care whether it’s either. Nolan commits that most egregious error of story-tellers, worse than implausible plots or artistic contrivance. He fails to make us care about his characters and what happens to them. So, when the bombs fall, the ships sink, and planes drop into the sea, the action is more balletic choreography than a terrifying, suspenseful experience. In the end, Nolan does not really tell us what happened at Dunkirk, neither the geopolitical realities nor the personal experiences of the men there who suffered and died, or who suffered and survived.

Nolan’s narrative failure is not a glitch, it is the inevitable outcome of his carefully constructed techniques, used in the service of projecting his worldview. In Nolan’s attempt to narrate the event of Dunkirk, both his artistic contrivances and his worldview are markedly postmodern, and postmodern narrativity is a leaky vessel—really a bucket without a bottom—when it comes to conveying historical remembrance or transcendent significance. Specifically, Dunkirk relies on the elevation of image over word, simulation, detachment, denial of true transcendence, and the sovereignty of the self in imposing structure on a primordially unpatterned reality.

Some key vignettes and details indicate Walter Lord’s book, The Miracle of Dunkirk: The True Story of Operation Dynamo provided Nolan the historical outline for his film. Lord’s book is a well-constructed narrative, combining oral histories from Lord’s interviews with survivors, along with his carefully researched accounts of the geopolitical realities. To be sure, his book has explanation and analysis, but also in his accounts of events and experiences, Lord’s words create word-pictures—vivid descriptions which enable the mind to imagine a scene, an event, an experience. This is the quintessence of oral and written story-telling. But it is not a reversible equation. Imagery may invite description, or augment a narrative, but one image or a succession of images alone cannot tell a story. What images can do is create subjective emotional associations within a viewer, and this seems to be Nolan’s intent when he strips as much dialogue and description as possible out of his movie and provides us instead with a cinematographer’s dream. By focusing on the visual—elevating image over word—he wants us to feel rather than think, to re-experience rather than remember.

http://www.rarenewspapers.com/view/560981?imagelist=1

The visual-emotive emphasis in Dunkirk serves as one ingredient in creating a simulation of reality, as do its draining of history and flattening of character. In The New Yorker, Richard Brody writes,

“The blankness of his characters is a directorial decision—not merely the mark but the essence of his overarching artistic strategy. With Dunkirk, Nolan has made what may be the first V.R. movie—one that does its best to put viewers literally into the position of combatants and participants in the Dunkirk rescue, as if viewers were meant to fill in the blanks of the characters’ inner lives with their own and imagine themselves to be fighting the Second World War for the very preservation of Great Britain.”

While Nolan’s simulation is not “pure simulacrum,” as in social theorist Jean Baudrillard’s analysis (the book to read is Simulations), where the image “bears no relation to any reality whatever,” it does pass the stage where “the image” (a movie about Dunkirk) would be the reflection of a “basic reality” (the historical Dunkirk), and arrives at the stage where the image masks and distorts reality. For Baudrillard, Disneyland—a paradigm of ahistorical detachment—”is a perfect model of all the entangled orders of simulation.” It is not difficult to imagine Dunkirk viewers becoming participants in a theme park Dunkirk-World.

The reviewer for First Things, William Doino, Jr., wrote, “For a person of faith, it is difficult not to think about God while watching Dunkirk.” I understand what he means. The evacuation at Dunkirk was called a miracle when it happened, from the sheer improbability of its success. A chain of “providential coincidences” began with the three-day halt of the German advance. The Luftwaffe, typically devastating in its role as airborne artillery, was frequently grounded due to heavy overcast and local storms. At the same time, the English Channel was unseasonably calm, allowing the Royal Navy and the “little ships” to pull men continuously from the mole and the beaches. The evacuation began with a National Day of Prayer called by King George VI and ended with a Day of National Thanksgiving.

Yet Doino’s reflection is ironic, given Nolan’s choice to depict the evacuation of Dunkirk not as indicative of a transcendent reality ordering human history, but as a desultory series of events in a maze of sheer immanence. Nothing is essentially related, and no superintending providence is evident or seriously suggested. What Nolan does suggest, as he also does in Interstellar, is that a virtual form of transcendence is available within the world, simply as a heightened experience of the world.

In offering his Dunkirk more as simulation and virtual reality than as historical reality and remembrance, Nolan seems to invite us—each of us as a detached self—to impose our own invented order and meaning on an assemblage of events. But what he is doing also resembles what Nicholas Wolterstorff, in Art in Action, called “world-projection”—the (wholly legitimate) artistic action of using a fictional world to make a claim or “put forth a message” about the actual world. And what Nolan wants to claim appears to resonate with Walter Lord’s historical judgment in The Miracle of Dunkirk:

“Dunkirk . . . should be regarded as a series of crises. Each crisis was solved, only to be replaced by another, with the pattern repeated again and again. It was the collective refusal of men to be discouraged by this relentless sequence that is important. Seen in this light, Dunkirk remains, above all, a stirring reminder of man’s ability to rise to the occasion, to improvise, to overcome obstacles. It is, in short, a lasting monument to the unquenchable resilience of the human spirit.”

But, whatever his intentions, Nolan’s deliberate “artistic strategy”, his projected worldview, and the postmodern sensibility of his Dunkirk narrative result instead only in providing raw material for our subjective interpretation, reflecting Derrida’s declaration in Writing and Difference, that the “absence of the transcendental signified extends the domain and the play of signification infinitely.” That some people might “impose” our knowledge of the historical facts or our theology on our viewing of Dunkirk doesn’t alter this assessment, nor can it “privilege” our interpretations over anyone else’s. Cut loose from the moorings of providence, history, and character, the events of Dunkirk can mean whatever we want them to mean.

Little-known Calvinist historian Dirk Jellema presciently warned of this emerging postmodern mindset several years before Derrida celebrated it. In a series of articles for Christianity Today in 1960, Jellema charted “The Rise of the Post-Modern Mind”:

“If the Christian mind held that the highest Reality is the Triune God, and that the Self is defined in terms of relation to Him; and if the modern mind held that the highest Reality is the Patterned Reality of nature, and the Self is defined by its having Reason and contacting that Patterned Reality; then the post-modern mind holds to the Self and the Unpatterned Reality. The Self creates whatever value and meaning there is; the mysterious Unpattern lies outside, impenetrable and awesome.”

If William Doino’s appropriation of the historical Dunkirk expresses the “Christian mind”, Walter Lord’s assessment reflects the “modern mind”, and Nolan’s presentation partakes of the “post-modern mind.” If his Dunkirk does not drown in the postmodern well, it certainly drinks from it.

If Dunkirk were merely about entertainment or even the aesthetic contemplation of Nolan’s admittedly striking cinematic art, none of this analysis would make much difference. But, as I have said elsewhere, movies have become a replacement for religion, the place where we communally remember and rehearse our shared symbols and archetypes. We look to movies the way we used to look to the Church and worship, to tell us who we are, why we are here, and how we should live. Films, like all works of art, can and often do express, not just an artist’s “private fancy”, but what the artist’s “community believes to be real and important,” as Wolterstorff puts it. This aspect of “art in action” is nothing new, of course. The art of the Counter-Reformation Baroque, for example, was employed in the reinforcement of a resurgent Tridentine Catholicism. But the advent of mass-culture heightened the social effect of art, especially for movies. More people have already seen Dunkirk than will ever see a Caravaggio painting or a Bernini sculpture. The widespread critical acclaim ensures that millions more will see it in the future, and that the film’s influence, both on filmmaking and cultural-historical remembrance, will extend beyond its time at the box office.

Despite its success as entertainment and art, Nolan’s Dunkirk leaves the question whether remembrance of the event of Dunkirk itself is well served by its postmodern narrative. True remembrance of the past requires true and well-told stories. Such stories and remembrance mediate our sense of transcendence, whether of national identity, cultural heritage, or the kingdom of heaven.

COMMENTS

11 responses to “Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk and the Problems of Postmodern Narrative”

Leave a Reply

Brilliant and beautiful. Thank you for helping me understand why it is that I appreciated Dunkirk, but didn’t love it.

Thank you, Margaret! Glad it was helpful.

Very interesting. Im pretty sure this is why Puritans banned theatre.

Heh. ;p

Calm down.

I am offended by your byzantine discourse on Nolan’s film because I think all of your caterwauling boils down to one simple idea: You didn’t like what Nolan was interested in doing with his film.

I don’t think it is as nearly as complicated as Nolan foisting a “post-modern” worldview on all of us while attempting to erase the historical reality of Dunkirk and turn it into the “choose your own adventure” that he secretly wants it to be in his heart of hearts. He’s an artist, and he brought a wholly unique artistic aesthetic to his film and I thought it was phenomenal.

I think it’s perfectly acceptable to not appreciate what he was going for, to not be moved by it–but what you are doing, ideologically, is hyperventilating silliness.

The first rule of a critic is to evaluate art on its terms, evaluate it in light of what it was trying to do—not what you wanted it to. The former is interesting, the latter is personal navel gazing.

Thank you for the detailed remarks. Of course I would disagree with your assessment, which seems to me very bit as Byzantine and hyperventilating as you think my essay is. I believe I have evaluated Nolan’s art on its own terms. Every point I make is substantiated either by careful analysis or by Nolan’s own expression of what he is doing. I am sure Nolan wants to be taken seriously, and I have done so. I have taken so much care and time with a movie review because Dunkirk is such a highly touted work of cinematic art that its influence, culturally and historically as well as artistically, will be considerable.

I didn’t want to come off so brash, but I think the combination of me being very gripped by the film, and having very definite ideas about the “proper” way to review a film made for an explosive combination 🙂

I agree you have taken him and his work seriously. I would love to launch into a detailed discussion about best practices in analyzing movies, but I’ll spare everyone on this particular go round 🙂

I get it! Trump actually is an artist, and I should have been evaluating him based on his artistic vision and whether he is accomplishing it, rather than engaging in my own hyperventilating silliness.

I know Brody’s disliked Nolan for being a pedestrian moralist … but based on that established complaint Brody has against Nolan I’m a bit surprised to see anyone contributing to Mbird invoking Brody against Nolan, seeing as Brody claimed that in Whit Stillman’s Love & Friendship Lady Susan Vernon didn’t break any of the actually important rules of morality, just the pedantic little rules of convention. It seems to me anyone with some familiarity with both Stillman’s films and Jane Austen’s writing would think the reverse is true, Susan Vernon breaks all the important “rules” of moral conduct by fastidiously keeping all the conventions that work at the surface of social interaction.

It seems there can be ways of highlighting Nolan’s historical weakness for writing vividly rendered emotionally warm characters without leaning on a point borrowed from Richard Brody. Nolan characters can be ciphers, symbols of ideas about life and in that respect Nolan doesn’t seem too different to me than someone like Terrance Malick, or casting a bit afield into non-Western film, Satoshi Kon

“For Christ did not send me to baptize but to preach the gospel, and not with words of eloquent wisdom, lest the cross of Christ be emptied of its power.”

Perhaps, we are all too quick to either praise or condemn a particular messenger’s art, style, etc. and thus lose focus of the Cross to which the message may (or not) point us to.

Easy for me to say, given that I share neither the aptitude nor appetite for art / culture that is enjoyed by others hereon. But, I’m guilty of the same tendancy within my own sphere of interests.