This look at the controversial new film was written by Caleb Ackley. (Spoilers ahead.)

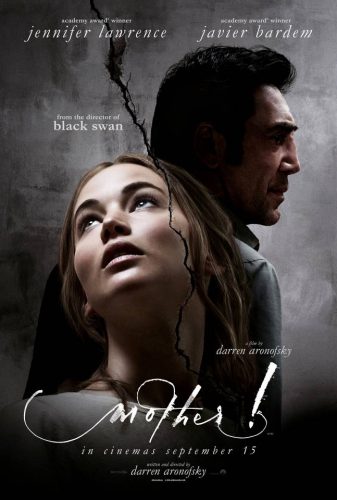

Mother! was advertised as a mystery-thriller and the trailer, which was riveting, left much to the imagination. Thus, on opening weekend, hordes of thrill-seeking men and women went to see it, each with their own set of expectations. Some came for horror, some expected gore, many came to see Jennifer Lawrence, that darling of the silver screen, be terrified herself; but most of all, they, and I in many ways, came that Saturday night to simply be entertained. Stuffed to the gills with excitement and no small amount of red licorice, there was also a niggling thought in the back of my mind…a persistent thought reminding me of how uncomfortable Darren Aronofsky’s other work had consistently made me feel over the years. Would this truly be a movie simply made for mass consumption? My mind said no, my heart said yes.

Mother! was advertised as a mystery-thriller and the trailer, which was riveting, left much to the imagination. Thus, on opening weekend, hordes of thrill-seeking men and women went to see it, each with their own set of expectations. Some came for horror, some expected gore, many came to see Jennifer Lawrence, that darling of the silver screen, be terrified herself; but most of all, they, and I in many ways, came that Saturday night to simply be entertained. Stuffed to the gills with excitement and no small amount of red licorice, there was also a niggling thought in the back of my mind…a persistent thought reminding me of how uncomfortable Darren Aronofsky’s other work had consistently made me feel over the years. Would this truly be a movie simply made for mass consumption? My mind said no, my heart said yes.

Fast-forward two hours, and we, the audience, let out a collectively held breath. My hand, which had been locked over my mouth for an unhealthy amount of time, fell to my lap. Eyebrows frozen high above their normal resting place, I looked at the friend with whom I’d attended, and slowly wagged my head in disbelief.

‘Wild ride’ hardly does this piece of work justice. The group sitting behind us left quickly, (very) audibly talking about their disgust for what they had just seen. ‘I didn’t come here to see a f*#$ing allegory; that’s what I go to CHURCH for,’ was a memorable comment I heard from someone quickly exiting. Other sage wisdom offered after the film was given by two middle-aged women sitting nearer the front. ‘That was amazing. We need a drink.’ Go ahead and get me one too, ladies.

The latest offering from the mind of Darren Arronofsky starts out innocently enough; a couple living in a gorgeous house deal with seemingly petty frustrations inherent in any committed relationship. Javier Bardem’s character, the unnamed ‘Him’, struggles as a writer trying to find inspiration. His wife, the frustratingly-lovely-even-when-she’s-painting Jennifer Lawrence, dotingly creates a beautiful space for Bardem to work, refurbishing their beautiful home with a deft hand and skillful eye.

Their ‘happiness’ is infringed upon when two people, first a chain-smoking Ed Harris, followed soon after by a ‘special lemonade’-loving Michelle Pfeiffer, come to stay without pretext or introduction. Quickly, group discussions devolve into uncomfortable standoffs; questions of ‘Why don’t you have kids?’ and statements like ‘This house is just setting, after all’ are left hanging in the air. Guilt and undisclosed desires hover suspended above the characters’ heads; the sword of Damocles, in this case, taking on the new form of a hundred sharpened daggers. This is only the beginning.

Soon, this unwelcome couple’s two sons make an appearance. Bickering over inheritance, they begin to scream at one another while Ed Harris’s breath rattles noticeably in his chest. The situation escalates and in the blink of an eye, a murder is committed. Lawrence, who is simply referred to throughout the film as ‘Mother’, is left to clean blood off the textured and beautiful floorboards. A stain of blood settles into the floor, refusing to be expunged, no matter how much cleaner is applied.

A wake is thrown in honor of the deceased, with the house that Lawrence has so meticulously pieced together serving as the backdrop. She begins to lose control of herself, no longer hiding behind social pleasantries to express what she is feeling.

As Lawrence continues to slip into desperation, people begin to stream into the house. Bardem’s character welcomes them all, delighted that his need for inspiration, with the advent of these new visitors, has at last been satiated. As the number of unnamed intruders increases, Lawrence’s house is transformed. Running from one room to the next, she tries desperately to quell the rising tide of anxiety as the beautiful rooms are marred by the stomping of inconsiderate feet.

Eventually, the initial influx of unwanted visitors subsides. Lawrence and Bardem are left to themselves once again, and are greeted with a new surprise; a child. Mother begins piecing the house back together in the ensuing months as Him begins to write profusely. The new book of poetry is quickly published and again we see the ominous march of smiling faces begin to crowd the front porch. Bardem’s character devours the attention, trying to convince Lawrence that this latest wave of visitors is good news. The house, again, is subjected to destruction, this time by those infatuated with Him’s poetical prowess. Sinks begin to crack, the larder is ravaged, and the rabid fans, desperate for ‘a piece’ of the home begin stealing, as vases, books, and even floorboards are snatched in the frenzy.

Forty minutes later, the house is no longer standing, Mother’s baby has been born, taken from her, killed, and cannibalized. Bombs have exploded, shrines have been erected, and altars have been built. Bardem stalks through the husk of what had once been his ornate country home. He carries the charred, hardly breathing body of Lawrence through the wreckage, laying her down on one of the few tables left standing.

Reaching inside her chest, he removes her heart as she draws her last breath. Grey and cracked, it quickly crumbles in his hand, revealing a translucent stone scored with fiery red at its centre. Placing the stone in a delicate stand, the house is suddenly remade. Rooms restored to their former glory, a woman’s shape also appears beneath the sheets of the bed within the expansive master bedroom. Cue credits.

Aronofsky’s films have always, either directly or indirectly, questioned existence and, by extension, the role that some ‘superior being’ would have in that existence. The earth, in this particular film’s case, is shown to be initially pure…a good creation. It is with the advent of mankind (Ed Harris’s character ‘Man’ and Pfeiffer’s ‘Woman’) that we see brokenness begin to take its heavy toll. This new darkness is spurred on by Bardem, in his quest for a kind of ‘glory’; demanding worship without regard to the beauty which already surrounds him. Lacking imagination, the character of the god which Aronofsky shows us on screen grows frustrated with his creation. Eventually, Bardem’s character sees fit to decimate his creatures, starting the whole broken process over again. By his actions, this supposed god, rather than showing any kind of divinely empathetic character, reveals himself to be little more than an exaggerated version of the humanity which he himself has created and subsequently destroyed for their selfishness. Driven by desperation, marked by cruelty, and infatuated with self-glory no matter the cost, there is little to love about this creator; a being from whom we should run, rather than worship.

COMMENTS

5 responses to “Mother!: Sinners in the Hands of a Petty God”

Leave a Reply

of possible interest for this movie, a recent Atlantic piece on the debt mother! owes to Artaud’s theater of cruelty.

https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2017/09/mothers-theater-of-cruelty/540780/

Although in an era in which TV ranges from The Walking Dead and Game of Thrones I’m not sure a theater of cruelty approach will necessarily work. Even if the shock of violence “works” what it means could still be open-ended. To go by the range of reviews I’m seeing one of the shortfalls of mother! as an allegory or parable is that any film critic can simply declare that the director’s intentions don’t matter and that the film is about X rather than Y (Richard Brody’s pieces on the film being the easiest case in point). Josephine Livingstone at The New Republic stopped just shy of saying that mother! would work more effectively as an allegory if the film understood the literary motifs it was appropriating for the allegorical level on the one hand and if the more “literal” reading wasn’t about a bad marriage running at cross purposes with the stated allegorical intent.

It kinda sounds like the film, as executed, is a gigantic mixed metaphor.

Valid points, to be sure. Your first comment, though, the one speaking of ‘declaring a director’s intentions as X rather than Y’, in my mind is a hallmark of film, rather than something that works against it. The director only has so much control over how one interprets what one sees on screen…and indeed I feel that a good film can and should be able to be interpreted in any number of ways with the foundational good direction+acting+screenwriting holding firm despite its varied reception.

Regarding your second point, while I think that this film can carry weight in a variety of metaphorical contexts, I think, and you can let me know what your take is once you’ve seen it if you haven’t yet, that it’s relatively clear by the time the credits roll, that this is no mere tale of ‘relational hardship.’

In addition, considering his larger body of work, I see ‘mother!’ as pretty par for the course in terms of disturbing content for Aronofsky. Iif that disturbance caught an audience member by surprise, I would direct them to take a closer look at the typically shocking (and often grotesque) films that make up his varied resume.

I appreciate the questions and observations, and I’ll look into that Atlantic article ASAP!

Well … let me provide a link to show that whatever Aronofsky may say he intended is actually irrelevant to reception. I’m not sure I entirely agree that an X vs Y distinction is simply inherent to film so much as it is inherently part of film criticism. We wouldn’t have this back and forth about an instructional video about how to repair a Keurig machine, I’m guessing.

But narrative film will invite such discrepancies because of, for want of a better phrase, the receptional-critical rules of the game for fictional film narrative. Thus … Richard Brody reminds us all that if mother! is an allegory it is so only by dint of fiat, having offered his own take on what he believes the film means in light of film history and the other films he’s seen.

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/mother-darren-aronofskys-thrilling-horrifying-nearly-unbelievable-satire-of-fame

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/darren-aronofsky-says-mother-is-about-climate-change-but-hes-wrong

Brody put things directly when he wrote, “In other words, “Mother!” isn’t an allegory except by directorial decree.”

Even if mother! is, as Aronofsky has been reported as saying, is intended to be an allegory about mistreatment of the earth, there’s an open question as to why such a thing should be presented in allegorical terms. Because, for instance, questions as to why Aronofsky decided to depict an allegory of the Earth as a famous pretty white blonde being abused come up.

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/darren-aronofskys-mother-has-a-muse-problem

And, at a more basic level, I saw the trailer for Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Sequel. If the topic is climate change is the cumulative carbon footprint that goes into making a film like mother! the best use of time, money and resources when the result is … mother! The theory that Aronofsky is indebted to Artaud’s theater of cruelty was one of the more interesting angles I’ve seen in discussing the film