The following comes to us from Cal Parks and is based upon material found in John Schofield’s Philip Melanchthon and the English Reformation (75-77).

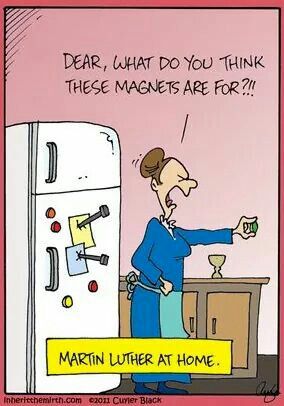

This year is the 500th anniversary of the so-called beginning of the Reformation, when Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the Wittenberg Castle Church. While a rather common and innocuous act (this was a way of inviting scholarly debate), it hit at a truly critical moment in European affairs, both spiritual and temporal. This event has become immortalized as a myth, and as a historian by trade, I tend to scoff at such reductions and over-simplifications as though it were a silly story of white hats vs. black hats.

This year is the 500th anniversary of the so-called beginning of the Reformation, when Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the Wittenberg Castle Church. While a rather common and innocuous act (this was a way of inviting scholarly debate), it hit at a truly critical moment in European affairs, both spiritual and temporal. This event has become immortalized as a myth, and as a historian by trade, I tend to scoff at such reductions and over-simplifications as though it were a silly story of white hats vs. black hats.

However, while Martin Luther was not the first one to oppose the Roman sacramental-industrial complex, he was one of the first to offer a radical deconstruction through the question of promise and faith. Did not Christ, the very Word of God revealed on the pages of infallible Scripture, bring about salvation for all who believe on Him and confess His person and work (c.f. Rom. 10:9)? If Christians had no faith in this very promise, and must be wary of God’s goodness and presence, what was any of it worth? Without faith, the entire Christian life was a lie, fully blackened by sin, and in terror of judgement. Luther’s “reformational breakthrough” was nothing less than deconstructing the entire Roman church.

It’s on this note that I bring up Rex Henricus, that famous killer of wives and promoter of Thomases (all four of his chief ministers were named Thomas: Woolsey, Moore, Cromwell, and Cranmer). The year is 1537. Henry has already broken away from Rome, declaring himself the head of the Church of England through Parliament’s Act of Supremacy. Anne Boleyn has already been married and buried, and the Henrician reforms are well underway. A group of senior clergy have compiled a confession of the reformed English faith, called Institution of a Christian Man, and sent it to the king for comment. The theology is striking.

The first line of creed states: “He is my very God, my Lord and my Father, and that I am His servant and His own son by adoption and grace, and the right inheritor of His kingdom.” Henry found this incomplete, and appended, “So long as I persevere in His precepts and laws.”

Elsewhere, Henry added editorials such as:

“The faith and belief and belief of this of Christ’s resurrection (we living well), is our triumph over the Devil, hell and death”;

“The penitent must conceive certain hope and faith that God will forgive him his sins, and repute him justified, and of the number of His elect children, not (only) for worthiness of any merit or work done by the penitent, but (chiefly) for the only merits of the blood and passion of our Saviour Jesus Christ.”

Reading this, it is very easy to laugh. Henry, the debauched, lust-filled, paranoid, egotist is going to throw himself upon his own good works? It is this man who will edit grace out of the English church? We living well? Only? Chiefly? Is this a joke?

But of course, this is no joke. This is life or death, and we, confused and arrogant sons of Adam, will always opt for the latter. We may laugh at King Henry, who is utterly a buffoon, but this man is truly a mirror on the wall. The stupid decisions, the self-deceiving justifications, the childish sense of pride over scraps, even as we leave a field of bodies in the wake. Are not we always tempted to say, with an almost comical sobriety, salvation is persevering in precepts and laws? We do not even care to hear God’s Law but would rather go about manufacturing our own codes and breaking those. For it is no wonder that Henry spent day and night looking for a technicality or loophole to get him out of the son-less marriage with Catherine of Aragon. Henry’s wrath and rage is nothing less than a vision of God, a picture of King Nebuchadnezzar on all fours like a beast. As that holy apostle told us, is it not God’s judgement to give us over to our wildest desires, becoming an animal in the process?

But even as we are always tempted to theologize like Henry, blindly casting about with wild and vain pronouncements, thank God that He has already declared on behalf of a corrupt and corroded creation. The glory of Jesus Christ still rings out, not in royal halls, but in alleyways and dark corners, where a message of redemption, peace, and, quite literally, resurrection meets with joyful tears and reception. This is what Brother Martin unleashed, blowing apart that Babylonian Captivity and heralding a return to Zion.

However, lest you think no one in England cared, that royal toady Thomas Cranmer even had enough of these editorials. After Henry, the new English creed passed on to the Archbishop, who had spent enough time with the Wittenbergers to know the truth. Cranmer, with an unusual ferocity, shot back:

“These two words (‘only’ and ‘chiefly’) may not be put in this place at any wise […] Certain it is, that our election cometh only and wholly of the benefit and grace of God, for the merits of Christ’s passion, and for no part of our merit and good works.”

Here, the king’s creature, totally dependent upon royal favor and patrimony, shot back. He had everything to lose in angering his master. May we be ever so bold with such a great and glorious truth. May this be what we carry in our hearts this year, the 500th anniversary of the Reformation.

COMMENTS

2 responses to “We Are All Henry VIII, or, Why the Reformation Is More Than Rome”

Leave a Reply

Worth the read alone: “However, while Martin Luther was not the first one to oppose the Roman sacramental-industrial complex, he was one of the first to offer a radical deconstruction through the question of promise and faith”

What a perfect description of the Roman church in Martin Luther’s day: a ‘sacramental-industrial complex’.

I’d no idea that Henry VIII was a proponent of adding ‘works’ to the grace of God, for salvation. What might he have done to his AOC, Thomas Cranmer, if the latter’s true views had been made public. We might not have had The Book of Common Prayer.

Excellent article. Thanks.