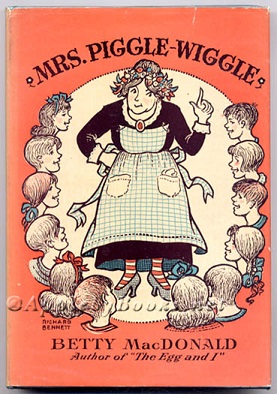

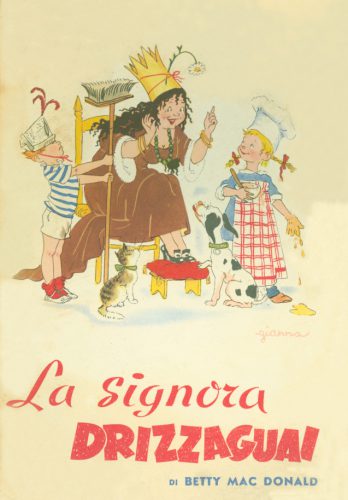

I’ve recently started reading the Mrs. Piggle Wiggle books to my 6-year-old. I picked them up because I remembered reading them when I was in elementary school, and because we could all use a little bit of Mrs. Piggle Wiggle in our lives. If you’re not familiar with the books, Mrs. Piggle Wiggle was created in the 1940s by Betty MacDonald. Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle lives in an upside-down house, she might have pirate treasure buried in her back yard, and she loves children. She soon acquires a reputation in the neighborhood for being able to “cure” common childhood “ailments”: not flu or measles, but behavioral problems like not wanting to go to bed, not picking up toys, or taking teeny tiny bites of food and eating too slowly.

I’ve recently started reading the Mrs. Piggle Wiggle books to my 6-year-old. I picked them up because I remembered reading them when I was in elementary school, and because we could all use a little bit of Mrs. Piggle Wiggle in our lives. If you’re not familiar with the books, Mrs. Piggle Wiggle was created in the 1940s by Betty MacDonald. Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle lives in an upside-down house, she might have pirate treasure buried in her back yard, and she loves children. She soon acquires a reputation in the neighborhood for being able to “cure” common childhood “ailments”: not flu or measles, but behavioral problems like not wanting to go to bed, not picking up toys, or taking teeny tiny bites of food and eating too slowly.

When I first read these books as a child, I loved them for Mrs. Piggle Wiggle’s gentle approach to behavior modification. She gently tricked children into correct behavior, without punishing or scolding, and without any expensive or intricate procedures. She used natural consequences, sometimes taken to hyperbolic lengths for the sake of fiction, to get children to modify their behavior themselves, and everybody is happy at the end of each chapter.

As a parent, I’ve noticed less about the children and the “cures,” and more about the mothers. The fathers are not particularly concerned with the children’s behavior, and if they are, their solutions generally involve ignoring the problem until it goes away, or corporal punishment. The mothers fret and worry and perseverate until the child is “cured,” and Mrs. Piggle Wiggle’s cures might be as much for the mothers as they are for the children. What stands out to me as a parent now, though, is how the mothers talk to each other.

Mrs. Prentiss, for example, has a child who will not pick up his toys, and so she picks up the phone and asks her friend for advice.

She took two aspirin tablets and then telephoned her friend, Mrs. Bags. She said, “Hello, Mrs. Bags, this is Hubert’s mother and I am so disappointed in Hubert. He has such lovely toys – his grandfather sends them to him every Christmas, you know – but he does not take care of them at all. He just leaves them all over his room for me to pick up every morning.”

Mrs. Bags said, “Well, I’m sorry, Mrs. Prentiss, but I can’t help you because you see, I think it is too late.”

“Why, it’s only nine-thirty,” said Hubert’s mother.

“Oh, I mean late in life,” said Mrs. Bags. “You see, we started Ermintrude picking up her toys when she was six months old. ‘A place for everything and everything in its place,’ we have always told Ermintrude. Now, she is so neat that she becomes hysterical if she sees a crumb on the floor.”

How about those names? I think Hubert and Ermintrude are long overdue for a comeback. But, again, what really strikes me are the conversations between these 1940s mothers. I tend to think of brag-plaining as a modern phenomenon, and something arising out of social media. “Oh my children are just so picky! They only eat organic grapes and won’t even touch the conventionally grown ones! #blessed #noGMOsinthishouse #anothertriptowholefoods #dirtydozen #organic4life #worthit.” But apparently, mothers have been rule-shaming one another since they had to call up the operator to make a telephone call. Eventually, the troubled mothers in the Mrs. Piggle Wiggle books find a sympathetic ear, they are eventually connected with Mrs. Piggle Wiggle. I suppose the 2017 version of this would be directing someone to the therapists covered by their Employee Assistance Program.

When hearing about the children’s problems, Mrs. Piggle Wiggle does not shame the mothers, or say they really should have done something differently all along. She has somewhat of a “what a pity” attitude about what has already happened, and a “let’s move forward” attitude about solving the problem. One little girl doesn’t want to take a bath, and so Mrs. Piggle Wiggle instructs the parents to let the dirt grow on her body until they can plant seeds in it – “The Radish Cure.” The boy who did not pick up his toys, Hubert, was left to his own devices for a while, until he could no longer leave his bedroom because all of his toys blocked the door, and had to be fed with the garden rake raised up to his window. This didn’t bother him, but not being able to leave the house to join his friends at the circus inspired him to clean up his room so he could leave. The mothers sort of fade out of the stories after the cures are complete, but I can imagine they have a huge sense of relief when Mrs. Piggle Wiggle helps them with their wayward children.

As a mother, I’m ashamed to say that I’ve probably been on both ends of that telephone conversation between mothers, in one way or another. What’s the old saying: “You can’t win at parenting, and if you think you’re winning, everyone else thinks you’re a jackass?” But there have definitely been times when I thought I was winning, and I’m quite positive that I was a jackass about it. I’ve also been on the receiving end of that kind of jackassery, when I was reaching out for help, immediately to be shut down by the 21st century version of Ermintrude’s mother, saying that if only I’d been smart enough to have girls instead of boys, or strategic enough to live near my extended family, or organized enough to have the college accounts fully funded before the children were born… I’d be just as good as they are. I understand where that self-righteousness comes from – it feels AMAZING, but it is also extremely isolating. Competitive parenting is exhausting, and you no sooner pat yourself on the back for your choices than your children do something completely mystifying and usually horrifying. There are rules of parenting are everywhere, but it’s somewhat comforting for me to know that mom-shaming wasn’t invented in our generation, because Ermintrude’s mother back in 1947 was a grade-A witch. I hope she’s very happy in her very tidy cocoon.

As a mother, I’m ashamed to say that I’ve probably been on both ends of that telephone conversation between mothers, in one way or another. What’s the old saying: “You can’t win at parenting, and if you think you’re winning, everyone else thinks you’re a jackass?” But there have definitely been times when I thought I was winning, and I’m quite positive that I was a jackass about it. I’ve also been on the receiving end of that kind of jackassery, when I was reaching out for help, immediately to be shut down by the 21st century version of Ermintrude’s mother, saying that if only I’d been smart enough to have girls instead of boys, or strategic enough to live near my extended family, or organized enough to have the college accounts fully funded before the children were born… I’d be just as good as they are. I understand where that self-righteousness comes from – it feels AMAZING, but it is also extremely isolating. Competitive parenting is exhausting, and you no sooner pat yourself on the back for your choices than your children do something completely mystifying and usually horrifying. There are rules of parenting are everywhere, but it’s somewhat comforting for me to know that mom-shaming wasn’t invented in our generation, because Ermintrude’s mother back in 1947 was a grade-A witch. I hope she’s very happy in her very tidy cocoon.

As Sarah Condon so aptly pointed out, this self-satisfied self-righteousness maybe isn’t all it’s cracked up to be:

Whenever you want to know what you would do in any given Gospel passage, just look at the people who are getting it wrong. They are there for a reason. God could have given us a whole body of scriptures with nothing but miracle stories and some solid life advice. Instead, the Gospels tell the story of Jesus and his group of bumbling jackwagons who ask too many questions, fall asleep like cranky toddlers, and betray the savior of the world for a bag of coins. Take it or leave it, but that’s us. It ain’t cute, but it’s true.

In Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle’s books, if you squint a little bit and turn the page sideways, you can see Pharisees and a non-prodigal son in Ermintrude’s mother. You can see the desperate sinner in the face of Hubert’s mother. From what we can see, only Hubert’s mother really feels set free at the end of the story. She feels the palpable relief of Mrs. Piggle Wiggle’s solution, and she is grateful. Ermintrude’s mother may have hung up the phone and thought, “Thank God I’m not like Mrs. Prentiss,” like the mid-century modern version of the Pharisee in the 18th chapter of Luke. We don’t know what happens to poor Ermintrude when her first college roommate smokes pot in their dorm room and doesn’t think to crack a window open first. We don’t know what happens to Ermintrude’s mother when darling little Ermintrude marries a hippie and lives on a goat farm in Oregon. Chances are, given the nature of children then and now, all of the mothers at some point had some comeuppance before their children flew from the nest. Children are a wonderful equalizer that way.

Long after I read the Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle books as a child, but before I had children myself, I convinced myself that if I just followed the rules of parenting, that everything would be OK and I probably wouldn’t mess up my children too badly. I read about feeding and sleeping, and I even read about reading. I could figure this out and get an A (or at least a passable B+ if I got really tired), and my husband’s superior genes could make up for my failings. The books about parenting feed into this idea that we have complete control, and that if you just do X, then Y will follow. I’m not sure how many actual children the writers of those books have encountered, but humans don’t tend to operate that way. But I think soon-to-be-parents eat up these rules because we want to tell ourselves the lie that “our children will be different.” That’s the lie that generations of young parents have told themselves, and I’m fairly sure that’s how the human race has survived. If we thought we couldn’t figure it out, why would we do this to ourselves? Children are a mystery–an often hilarious and disgusting mystery. Before I was a parent, I underestimated both my need for forgiveness in puzzling out this mystery, and also the number of opportunities I would have for another chance to get it right.

Long after I read the Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle books as a child, but before I had children myself, I convinced myself that if I just followed the rules of parenting, that everything would be OK and I probably wouldn’t mess up my children too badly. I read about feeding and sleeping, and I even read about reading. I could figure this out and get an A (or at least a passable B+ if I got really tired), and my husband’s superior genes could make up for my failings. The books about parenting feed into this idea that we have complete control, and that if you just do X, then Y will follow. I’m not sure how many actual children the writers of those books have encountered, but humans don’t tend to operate that way. But I think soon-to-be-parents eat up these rules because we want to tell ourselves the lie that “our children will be different.” That’s the lie that generations of young parents have told themselves, and I’m fairly sure that’s how the human race has survived. If we thought we couldn’t figure it out, why would we do this to ourselves? Children are a mystery–an often hilarious and disgusting mystery. Before I was a parent, I underestimated both my need for forgiveness in puzzling out this mystery, and also the number of opportunities I would have for another chance to get it right.

I don’t know what Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle would do for an ailing parent. She seemed to specialize in pediatric behavioral modification, and I don’t know how she would treat damaged friendships, or procrastinating parents. I hear echoes of Gospel truth, though, in Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle’s “what a pity” attitude about the past, and in her hope for the future. I know that we belong to Jesus, both children and parents alike. I’d like to think that I’m more aware now of my need for Jesus’ all-encompassing love and forgiveness than I was ten years ago, before these humbling children were placed in my life. But I know that as soon as I start to sound like Ermintrude’s mother, I’m dangerously on the edge of not knowing how much I need forgiveness. Like the little boy who would not clean up his room, I’m in danger of missing out on the circus with my friends if I insist on my own way. We can’t win at parenting.

Children aren’t the only reminders of our need for forgiveness and mercy, of course. We’re reminded of our shortcomings and brokenness often enough by stepping on the scale, or checking our bank balance, or navigating relationships with other adults. As soon as we get all of the laundry cleaned and put away, we dirty more clothes just by existing. With all of those reminders of our own frailty, we also need reminders of our forgiven-ness, and of God’s grace. The bad news and the good news is that we’re all a little bit Ermintrude’s mother and Hubert’s mother, and that we’re all forgiven for that.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle and the Motherhood Cure”

Leave a Reply

There is nothing (nothing) I loved more than reading to our boys virtually every available night (5-7 per week) until the oldest was 14 (we had to finish the Harry Potter Series). it was a dozen years of unconditional good…thankyou..

Carrie, you are an amazing mother and author! You are also an incredible daughter, wife and friend. Thanks for sharing these thoughts. Congratulations on your articles being published in the Anglican Digest! Keep on writing!

?