“A typical American film, naive and silly, can — for all its silliness and even by means of it — be instructive. A fatuous, self-conscious English film can teach one nothing. I have often learnt a lesson from a silly American film.”

So judged the famously austere Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, fanatical opponent of intellectual affectation and devotee of Detective Story Magazine. Though I knew this remark from memory (they make you learn it when you send in your bottle caps to join the Wittgenstein Fan Club), Tasha and I did not hire a babysitter and head out Friday night in order to be edified. Our motives were strictly base, and Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 played to them. The film is chaotic, noisy fun; like its predecessor, superhero nonsense weighted toward the self-referential and absurd. No one should expect depth from it. But in line with Wittgenstein’s observation, there is a kind of instruction that only comes sub contrario, under the form of its opposite. Guardians 2 is a silly American film about made-up people who for the most part aren’t even human — but it is not ignorant of humanity.

This is the sequel to a Marvel Studios blockbuster; I won’t bother to rehash the plot in any detail. As for spoilers, consider yourself warned. Action picks up where the last film left off, the Guardians jetting around the galaxy doing difficult jobs for cash, and pocketing the occasional rare valuable on the side. Groot, having sacrificed himself to be reborn from a seed, is here still very much a sapling — or rather, a toddler. The character’s behavioral resemblances to our son were not lost us. Coincidence, I am sure (the timeline on which such work is produced is fairly long), but our brother-in-law Scott did significant design and modeling work on toddler Groot (not everyone can have a sexy job like pastoring a church in Lancaster, PA).

The pulse of the story is introduced by way of two characters: Gamora’s (Zoe Saldana) murderous sister and rival, Nebula (Karen Gillan), and Peter Quill/Starlord’s (Chris Pratt) biological father, the mysterious alien Ego. Nebula is captive and driven by revenge and sibling rivalry. Ego’s motives are less clear — superficially, he only wants to reconnect with his long-lost son. Further complicating the mix is the disgraced Ravager captain Yondu (Michael Rooker), he of bad teeth, rough manners, head fin, and telekenetically-controlled arrow. Yondu is the Guardians’ great frenemy; he raised Quill (constantly threatening to eat him), and kept him from Ego (for good or ill), but appears thoroughly selfish and venal, if not utterly villainous.

Beneath the quips and anarchy, the film bears an unexpected darkness. Its violence is largely, but not exclusively, cartoon. Frozen corpses string out behind the mutinous Ravagers’ ship as they dispose of the crew’s remaining loyalists. Yondu’s vengeance on the same crew is an operatic feat of bloodshed, his darting red arrow hypnotic, a trail of effortless death more reminiscent of John Wick than anything of the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

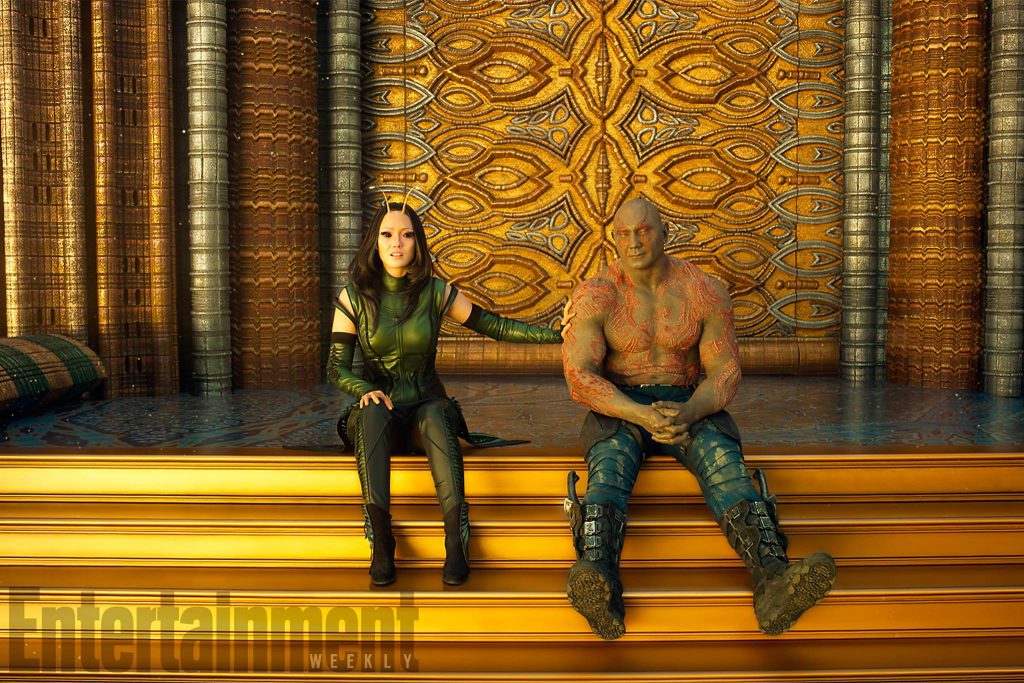

The broadly-drawn characters are not emotionally invulnerable. Drax is a comic high point, but also a deeply sad character, somehow rendered plausible in his bluntness and awkwardness by former WWE star Dave Bautista. Rocket, for all his snarl, is a frightened animal, insecure and lonely. Even young Groot is no stoic. The first film suffered a bit from unconvincing villains, but here each has a hint of depth. Nebula is a wounded soul, her hatred born of jealousy of her sister and abuse at her father Thanos’ hands. Yondu is an outcast so convinced of his own worthlessness that he hides his one good work, protecting Quill. Only Ego is irredeemable, having intentionally snuffed out love and compassion, connection with anything other than himself, in pursuit of infinite self-expansion.

That self-expansion project serves as the device behind the film’s primary conflict and its point of greatest theological heft. Ego, charmingly played by Kurt Russell, is a god of sorts. His name expresses his nature: a celestial being who slowly constructed himself over the aeons, effectively immortal, and nigh omnipotent as long as he remains connected to the “light” that is his essence. Having once sought out life other than himself, but disappointed by it, he is engaged in an age-long project to disperse his seed through the universe and, in essence, call it back to himself. Ego will be all in all. Peter Quill is his son by an Earth woman, and the only other being to share in Ego’s essence. Ego is utter selfishness within a glorious exterior — the creator of a world of delights and the killer of the woman he loved, whose simple otherness threatened his higher purpose of infinite growth.

It would not be too much, I think, to read into Ego a critique (intentional or not) of certain ideas within both classical and contemporary theology. Like Aristotle’s God he is sheer self-regard, the highest and best thing contemplating itself alone, as anything else would be unworthy. His development is quintessentially modern, a Hegelian self-realization in process, the self thinking itself through time. When he refers to himself as a god, “small G,” one detects a hint of false modesty — speculatively, eschatologically, Ego is all that is. Along similar lines, we can see a twisted version of the Platonic scheme of exit and return in Ego’s grand plan, as otherness emerges from the One only to be drawn back into it.

Ego is Quill’s father, but not his only father. Having seen the fates of Ego’s other children, Yondu raised the orphan Quill and kept him from the luminous being who sought him. Yondu is not a good man, or a kind man. Neither is he pleasant to look at, pleasant to listen to, or pleasant to work for. There is, you might say, “no beauty that we should desire him.” Peter Quill’s true biological father is a heavenly being of unimaginable glory — but as is made apparent, that one never loved him at all. Yondu does love Peter, like a true father should, and this love comes to expression in the only way that can make it as certain as it is paradoxical — he lays down his life for his son.

I did not expect to find, in a Guardians of the Galaxy film, even a veiled expression of glory versus the cross, of the God who reveals himself under the form of his opposite, of the difference between the true God and all pretenders, however beautiful and good and intellectually respectable they might seem. But there it is — the only God that matters is the one who loved me and gave himself for me. That is his one ineradicable mark. The difference between Ego and Yondu extends even into the nature of their hold on Quill. Ego’s connection to his offspring is in his essence, the light. It is genetic and intrinsic. Quill matters to Ego merely because he is like him and contains a piece of him. But Yondu’s hold, which proves the stronger, is entirely extrinsic. He adopted Quill and raised him — to be a pirate and thief, to be sure — but let that not obscure the beauty of this wholly imputed connection. Ego’s “love” is a love which does not suffer because it looks only inside itself; Yondu’s love is self-abandonment, which sees only the beloved.

The juxtaposition of Ego and Yondu also highlights another way this film cuts slightly against the grain. Given the level of disruption in contemporary family life, it is no surprise that popular cinema has explored the phenomenon of family as found and constructed, rather than as simply given. In this world, we may have to make family for ourselves where and when we can. The first Guardians took up that theme, as have the Avengers movies and recent Star Trek pictures. National Review‘s David French recently wrote a somewhat surprising recommendation of The Fast and the Furious around this concept. Guardians 2 does not contradict those approaches, but it does offer a significant qualification. Against the view that family is therefore a form of choice, a self-construction project (akin to Ego’s?), the picture emphasizes the goodness and necessity of relationships that we did not choose. Gamora and Nebula finally are sisters, however conflicted they may be about that. Ego is Quill’s biological father, but he did not raise him and cannot simply establish a relationship by jetting in on an egg-shaped spaceship; Yondu has the relationship, strained though it may be. Quill’s final realization in the film is that he had “a pretty cool father.” He did not choose him, but in a mysterious and rough-shod way, he was loved.

COMMENTS

5 responses to “The Father You Have, Not the Father You Want: Cross and Glory in Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2”

Leave a Reply

Interesting. Thx.

Phenomenal analysis. Loved the movie.

I find that Hollywood has circled around a dual theme, that keeps reoccurring: the mortal (good) vs. the immortal (bad) and the adoptive parent-mentor (good) vs. normative father (bad). As some philosophers and historians speculate, the birth of the modern is the death of the father and the death of god. Despite Hollywood’s critique, Christ seems unconquerable, and the Gospel still resounds forth.

Thanks Adam for recognizing this and writing about it.

Yondu surrendering himself to death on the tail end of, “He might have been your father, boy- but he wasn’t your daddy!” ministered mightily to this poor sinner encumbered with his own daddy issues. This was great, Adam, thanks.