I.

The great error in Rip’s composition was an insuperable aversion to all kinds of profitable labor. It could not be from the want of assiduity or perseverance; for he would sit on a wet rock…and fish all day without a murmur, even though he should not be encouraged by a single nibble.

— Washington Irving, “Rip Van Winkle”, 1819

Between 1959 and 1968—the year he was assassinated—Martin Luther King, Jr., gave at least five speeches in which he referenced the early 19th-century American short story, “Rip Van Winkle”. These speeches included a commencement address at Morehouse College, an address at the Methodist Student Leadership Conference, a commencement address at Oberlin College, a lecture at the Unitarian Universalist Association General Assembly, and his last Sunday sermon, preached as if to the nation, from the pulpit of the Washington National Cathedral. The story also appeared in his last book, aptly titled, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community?

Notably, three out of these five speeches were to student audiences. King used the story to teach the importance of vigilance and engagement amid the social challenges of the time. In his retellings, he always zeroed in on one particular detail—the sign on the inn in the little town. As he explained, when Rip first went up the mountain, “the sign had a picture of King George III… When he came down, 20 years later, the sign in the inn had a picture of George Washington.” Upon seeing this, Rip was “completely lost; he knew not who he was.” According to King: “This tells us that the most striking thing about the story of Rip Van Winkle is not nearly that he slept 20 years, but that he slept through a revolution.” And there, for King, lies the real lesson for the rest of us. As he continued: “all too many people fail to remain awake through great periods of social change… But today our very survival depends on our ability to stay awake, to adjust to new ideas, to remain vigilant and to face the challenge of change… Together we must learn to live as brothers or together we will be forced to perish as fools.”

Like most of King’s themes, this one certainly has its Biblical roots—it calls to mind Christ’s apocalyptic parable of the ten virgins/bridesmaids, or Christ’s repeated requests to his disciples in Gethsemane that they “stay awake and pray” with him as he awaits his arrest, though each time they still nod off. (“The spirit is willing, but…”) It’s a theme that is especially well-suited to tumultuous times, like King’s own. In a way, King’s sermon on the Rip Van Winkle story served as a parting wish and warning to the next generation. Taylor Branch explains: “King pleaded for his audience not to sleep through the world’s continuing cries for freedom”—not to make the mistake that, as in another of Christ’s parables, the rich man made with Lazarus, but instead to “act toward all creation in the spirit of equal souls and equal votes… to find [our own] Lazarus somewhere, from our teeming prisons to the bleeding earth.” A stirring call, indeed.

Today, as we too labor through a time of intensifying social unrest—what Rev. William Barber II has called “the birth pangs of a Third Reconstruction”—this appeal for vigilance and engagement is surely as relevant as ever.

And yet when I recently came across one of these great King speeches, I have to say, I felt myself pushing back. I recoiled ever so slightly at his exhortation to “remain awake.” Maybe it’s just the language that bothers me. But it’s been an exhausting few months in this country—frankly, an exhausting few years. It’s not a stretch to say that our recent politics have literally been making some of us ill. I don’t disagree with King in principle, but in practice I wonder about the physical and emotional toll implied by such vigilance. In his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail”, King made a similar kind of appeal: “Human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability; it comes through the tireless efforts of men willing to be co-workers with God.” That used to be one of my favorite inspirational quotes, but now I’m not so sure. I struggle with words like “tireless”, or the implied confidence that through such conscious efforts we as individuals might alter the course of history. It’s not that I disagree with him in principle; it’s just that I’m not as confident in human ability, in my own ability, as I used to be.

And yet when I recently came across one of these great King speeches, I have to say, I felt myself pushing back. I recoiled ever so slightly at his exhortation to “remain awake.” Maybe it’s just the language that bothers me. But it’s been an exhausting few months in this country—frankly, an exhausting few years. It’s not a stretch to say that our recent politics have literally been making some of us ill. I don’t disagree with King in principle, but in practice I wonder about the physical and emotional toll implied by such vigilance. In his famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail”, King made a similar kind of appeal: “Human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability; it comes through the tireless efforts of men willing to be co-workers with God.” That used to be one of my favorite inspirational quotes, but now I’m not so sure. I struggle with words like “tireless”, or the implied confidence that through such conscious efforts we as individuals might alter the course of history. It’s not that I disagree with him in principle; it’s just that I’m not as confident in human ability, in my own ability, as I used to be.

Perhaps it’s worth mentioning here that before costing him his life the Civil Rights Movement took a massive toll on King’s health. As Taylor Branch explains: “When they did the autopsy, they said he had the heart of a 60-year-old”—King was 39 at the time. He almost certainly would have worked himself to death had he not first been cut down by an assassin. And in fact, in the tough years preceding his death, King “was constantly fantasizing about getting out of the Movement.” Branch is quick to add that King’s commitment to the cause never wavered, but who can blame him for wanting a little respite? In just over a decade, this modern-day apostle “traveled over six million miles, gave more than 2,500 speeches and wrote five books.”

Perhaps the cause of my own present wariness with such appeals for ever greater vigilance and engagement—so commonplace in activist circles these days—is simply this: over the past few months, I have felt the need for deep rest and its soothing power more than at any other time in my life. Never has sleep been sweeter a grace to me than during the “honeymoon phase” of Donald J. Trump’s presidency. Call me lazy or lax all you like, but in such times, I can relate to a deadbeat like Rip. These days, I think we all need as many ways to meaningfully disengage as to engage. As for me, I have craved and loved this “little death” of sleep, a most thorough disengagement, which falls nightly over my worried mind like dew from heaven.

II.

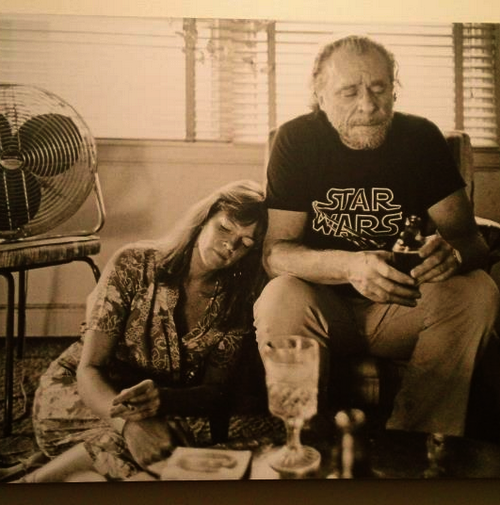

Without stopping entirely and doing nothing at all for great periods, you’re gonna lose everything… [T]here has to be great pauses between highs, where you do nothing at all. You just lay on a bed and stare at the ceiling. This is very, very important… And how many people do this in modern society? Very few. That’s why they’re all totally mad, frustrated, angry and hateful. In the old days, before I was married… I would just pull down all the shades and go to bed for three or four days. I’d get up to shit. I’d eat a can of beans, go back to bed.

— Charles Bukowski, Interview magazine, Sept. 1987

This topic of sleep as grace came up in a discussion I had a few weeks ago with a dozen or so of my church friends at our monthly “Theology on Tap” gathering. The actual discussion topic for that evening was “liminal space”—the thin space or threshold on the boundaries between the familiar and unknown. As Richard Rohr writes, liminal space is “the realm where God can best get at us because our false certitudes are finally out of the way… The threshold is God’s waiting room. Here we are taught openness and patience as we come to expect an appointment with the divine Doctor.”

After a short introduction, we launched into a group discussion around this question: how do you experience the divine in the mundane parts of your life? Answers from my church peers included—in afternoon jogs, water aerobics, folding laundry, spending time in nature, watching movies, sitting alone in the sanctuary, listening to music while driving, taking two-hour-long baths, spending time with my kids, etc. Listening to others share, my own answer soon became apparent: lately, I have experienced God most in sleep. For months, sleep has been my “liminal space”—the threshold in my life in which I do my best, perhaps my only, real waiting. Sleep is the space where, amidst my constant distractedness and pathological angst, I am “taught openness and patience”, where I “come to expect an appointment with the divine Doctor.”

It seems so obvious, almost banal, for me to write that now. But sleep would never have been my answer to that question in years past. I think I’ve long felt that ‘experiences’ of God had to come through some act or effort on our part: worship, prayer, meditation, exercise, community service, shrooms, forest-bathing—whatever. Sleep seems so passive. And when it’s over I’ve got no good stories or pictures to share, no soundbites of inspiration to take with me to work the next day. But if I had to look back on the past decade of my life, humbling as it’s been, and pinpoint the one thing on a day-to-day basis that has helped hold my body and soul together more than anything else, it would probably be sleep. Sleep is, after all, how we spend about a third of our lives, and it’s the one way I am able to consistently recover from the emotional pain of the day that doesn’t require energy and is not self-destructive. At a time in my life like this one, when the waves of emotional distress just keep coming, I suppose it makes sense that I’d crave sleep, that I’d become more acquainted with its soothing, healing, power.

I’m a liberal Democrat and a second-year English teacher at a public middle school in a low-income urban neighborhood. Sure, I go to work most weekdays and try to make a difference and I’m out there marching in the streets with the best of them probably once a week now, but I need a lot of damn soothing. I’m weak. I’m a bruised reed, a smoldering wick. I’m no Martin Luther King. Heck, Martin Luther King was no Martin Luther King. To paraphrase Richard Rohr, I need something every day that can transform my pain so I won’t transfer it onto myself or others. We would love to believe that we can just think or act our way out of misery—that we can just will ourselves to feel better through positive thinking and healthy living, but the reality is that we need ways to get our misery out of our own hands so someone else can deal with it. In other words, we need God. We need be able to close our eyes and float awhile on a dark ocean of grace. We need a time when, as Wendell Berry puts it, “The body… is still; / Instead of will, it lives by drift”. That’s what sleep is. And it doesn’t matter whether I have “earned” it—whether I have put in my hours working or volunteering or protesting—it’s a gift, and one which even the most frustrated insomniacs eventually have no choice but to accept.

I’m a liberal Democrat and a second-year English teacher at a public middle school in a low-income urban neighborhood. Sure, I go to work most weekdays and try to make a difference and I’m out there marching in the streets with the best of them probably once a week now, but I need a lot of damn soothing. I’m weak. I’m a bruised reed, a smoldering wick. I’m no Martin Luther King. Heck, Martin Luther King was no Martin Luther King. To paraphrase Richard Rohr, I need something every day that can transform my pain so I won’t transfer it onto myself or others. We would love to believe that we can just think or act our way out of misery—that we can just will ourselves to feel better through positive thinking and healthy living, but the reality is that we need ways to get our misery out of our own hands so someone else can deal with it. In other words, we need God. We need be able to close our eyes and float awhile on a dark ocean of grace. We need a time when, as Wendell Berry puts it, “The body… is still; / Instead of will, it lives by drift”. That’s what sleep is. And it doesn’t matter whether I have “earned” it—whether I have put in my hours working or volunteering or protesting—it’s a gift, and one which even the most frustrated insomniacs eventually have no choice but to accept.

In the weeks after Trump’s stunning victory, everyone around me was talking about the need for action, mass protest, some colossal effort to counteract this outrageous development. I was talking about it too. But all I really felt like doing was sleeping. If I hadn’t had to work I absolutely would have pulled a Bukowski and just slept the better part of a week. Maybe that’s what I needed. And maybe a few times since too. I was effectively depressed for three months after the election. Only lately have I started to feel some physical and emotional buoyancy again. And sleep, of course, has had a massive role to play in getting me there.

Philosophers from Heraclitus to Aquinas to Descartes have waxed eloquent about sleep’s sweet power, especially in times of distress. But what is it exactly that sleep does to us? It’s still very mysterious. As a 2013 article in The Atlantic put it: “Unlike other basic bodily functions, such as eating and breathing, we still do not fully understand why people need to sleep.” It was around that time this February—when I was first starting to feel healthy again—that I stumbled upon an article in The New York Times that confirmed some of my own theories about sleep. As Carl Zimmer writes, “Over the years, scientists have come up with a lot of ideas about why we sleep. Some have argued that it’s a way to save energy. Others have suggested that slumber provides an opportunity to clear away the brain’s cellular waste…” But recent studies suggest that sleep has an important editing role to play in our lives. Zimmer continues:

We sleep to forget some of the things we learn each day.

In order to learn, we have to grow connections, or synapses, between the neurons in our brains. These connections enable neurons to send signals to one another quickly and efficiently. We store new memories in these networks.

In 2003… biologists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, proposed that synapses grew so exuberantly during the day that our brain circuits got “noisy.” When we sleep, the scientists argued, our brains pare back the connections to lift the signal over the noise.

Zimmer goes on to explain how the recent research supports this hypothesis. When I read that I thought: that’s it, that’s what sleep does! Our thoughts and feelings are ‘noise’ we respond to obsessively throughout each day, noise that teaches us a great deal but that often overwhelms our best efforts to focus or to love others or to remain calm about something we fear, resent, regret, or desire. When we sleep, we have no choice but to relax, to release those thoughts and feelings we’ve been grasping so tightly throughout the day, and let them be sifted like wheat.

In this way, sleep is a kind of poor man’s meditation. It allows us to experience some detachment from the exhausting self without exerting conscious effort to do so. It’s a nightly vacation from the toils and terrors of this troubled world we share, and these troubled souls we bear. Sleep allows the pain to subside. It turns down the heat on the front burner of our minds. In that way it’s a place where God transforms us and prepares us. It’s as if through sleep God plays our editor-in-chief. Our mental newsfeed shuts down and we open ourselves up to God, as if to say: do your work with me, I am a sinner in need of a physician. Sleep wipes away so much of what we need freed from and lets us keep so much of what we need learn. What a gift! Frederick Beuchner captured this point perfectly in a remarkable passage from The Alphabet of Grace:

Life is grace. Sleep is forgiveness. The night absolves. Darkness wipes the slate clean, not spotless to be sure, but clean enough for another day’s chalking. While he sleeps and dreams, Prince Oblonsky is allowed to forget for a little, to unlive, his unfaithfulness to his wife—his dreaming innocence is no less part of who he is, no less transfiguring and gracious, than his waking adultery—and thus he is cleansed for a little while of his sin, emptied of his guilt. And so are we all.

So are we all. Sleep is that one time during the day when I relinquish this beloved delusion of control and just float like driftwood. And in that sense, falling asleep is ultimately an act of trust. We really don’t know what will happen to us. (“If I should die before I wake…”) I suppose that is in part the terror of nightmares—we are caught in stories that we do not control. But of course, we are already in a story that we do not really control! I cannot fix this world. I cannot fix my students. I cannot even fix myself. And I also cannot accept things the way they are. But at least in sleep, I am able to rest awhile in the grace of the world. I don’t have to move a muscle. I can just lay there. Tomorrow will take care of itself!

In these strange times, my body still churning, this is where I have found God—in this “little death” of sleep. No matter what happens today, no matter what we’ve done or left undone, no matter how bad it gets, eventually you and I will have to sleep. In spite of our most stubborn attempts at despair, sleep will have its way with us. It will do its monumental work of stitching us back together and tomorrow the sun will rise and we will, God-willing, begin again.

III.

Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget

falls drop by drop upon the heart,

until, in our own despair,

against our will,

comes wisdom

through the awful grace of God.— Aeschylus, quoted by Robert Kennedy, April 4, 1968, Indianapolis, Indiana

As deeply unsettled as our nation is in 2017, it’s worth recalling that our present unrest still pales in comparison to that which we faced a half-century ago. The late 1960s was a period that traumatized the American public and set in motion epochal political shifts that continue to play out to this day. And no year stands out more from that time than 1968—the year, of course, that Americans witnessed the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bobby Kennedy, as well as record anti-war protests, the Orangeburg massacre, the proliferation of far-left groups, the candidacy of George Wallace, chaos at the Democratic National Convention, and massive riots in urban centers across the nation that in some cases destroyed entire neighborhoods.

Yet, one well-known moment of grace from that difficult year may be instructive. It was the night in April, after learning of King’s assassination, that “RFK Saved Indianapolis”, or as I’d call it, the night the Spirit moved Bobby Kennedy. Here’s the backstory:

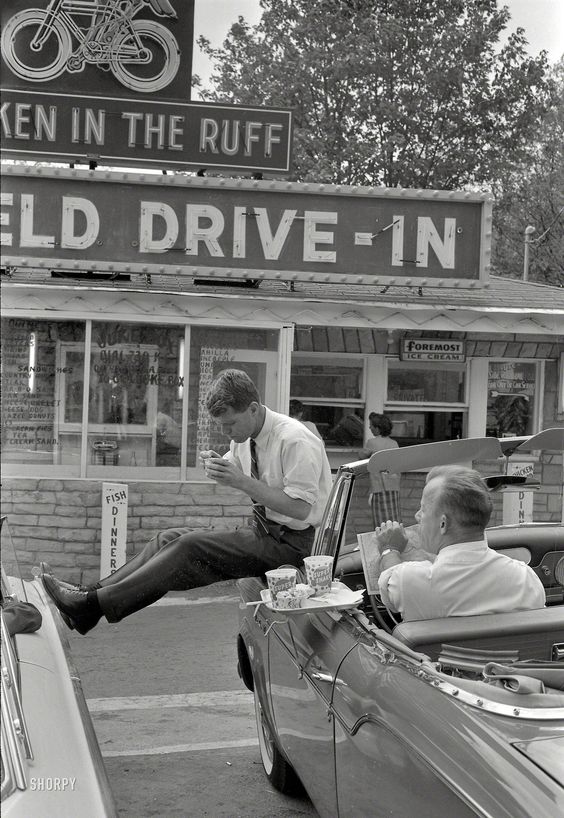

Kennedy, who was running for president, was scheduled to make a campaign speech [in Indy]… days before the Indiana Democratic primary. He was popular among the black community, and in an effort to get more blacks registered to vote, he wanted to speak in the heart of Indianapolis’ inner-city.

Shortly before his speech, as Kennedy’s plane landed in Indianapolis, the senator… learned that Martin Luther King Jr. had died from an assassin’s bullet.

Indianapolis Mayor Richard Lugar, fearing a race riot, told Kennedy’s staff that his police could not guarantee Kennedy’s safety… Racial violence indeed would later sweep the country, with riots in more than 100 cities, 39 people killed and more than 2,000 injured.

Lugar urged Kennedy to cancel his speech. But Kennedy insisted…

The audience in Indianapolis was estimated at only about 2,500 people, but they were influencers, members of young, somewhat radical black groups…

The speech began an hour late, around 9 p.m. Kennedy had effectively had the car-ride from the airport to prepare some remarks, but he mostly spoke from the heart. He got up on a flatbed truck and told his audience the tragic news most of them hadn’t yet heard—in the video, you hear their shrieks of anguish. Then Kennedy began his “but I tell you, love your enemies” appeal:

In this difficult day, in this difficult time for the United States, it’s perhaps well to ask what kind of a nation we are and what direction we want to move in. For those of you who are black… you can be filled with bitterness, and with hatred, and a desire for revenge.

We can move in that direction as a country, in greater polarization – black people amongst blacks, and white amongst whites, filled with hatred toward one another. Or we can make an effort, as Martin Luther King did, to understand, and to comprehend, and replace that violence, that stain of bloodshed that has spread across our land, with…compassion, and love.

Dr. King couldn’t have said it better. Yet, what must have made this plea powerful to Kennedy’s audience was what came next—a reference to his own walk with grief, perhaps the root of his own transformation. It was a signal that, despite their differences, his audience’s grief was a grief he at least partly understood, and their cross was a cross he at least partly bore with them:

For those of you who are black and are tempted to…be filled with hatred and mistrust of the injustice of such an act, against all white people, I would only say that I can also feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling. I had a member of my family killed, but he was killed by a white man.

At this point, being a candidate for President, you might have expected Kennedy to transition away from sentiment toward some more specific call to action. You might have expected him to make his call for more voter registration, canvassing, protests, etc. Instead, Kennedy quotes his “favorite poet” Aeschylus and then makes a request that to many might have seemed apolitical:

I ask you tonight to return home, to say a prayer for the family of Martin Luther King… but more importantly to say a prayer for our own country, which all of us love – a prayer for understanding and that compassion of which I spoke.

For whatever reason, this short speech seems to have worked, or at least helped: unlike so many other cities, including my own, two hours away, downtown Indianapolis was not consumed by race riots that spring. But Kennedy had not asked his audience to give up and go home. He called on them instead to shun the despair that leads to violence and turn to the source of all hope and strength—then to join him again in dedicating their lives to the hard, slow work of “[taming] the savageness of man and [making] gentle the life of this world.”

Sadly, the consequences of the race riots that spread through cities across the nation that year would still prove disastrous for many other inner-city communities. It was a moment that has shaped American politics and scarred race relations ever since. The racial issues of the time—more than the response to abortion—likely even helped precipitate the rise of the Religious Right, which has dramatically impacted the practice of our own religion in this country to the present day. But the story of the Kennedy speech gives us a hopeful example of a different way through all of this: something touched that small group of political activists that night. Those few thousand in attendance took his words home with them—they reflected, perhaps prayed, and mourned, and slept. And somehow, their righteous rage and bitter grief was transformed, so that they chose not to rain fire down upon their own city, but instead to follow the much less emotionally satisfying way of justice, which always leads through love. I like to think that, as Aeschylus put it, as they slept that night—in their despair, against their will, wisdom came to those mourning souls, “through the awful grace of God.”

Sadly, the consequences of the race riots that spread through cities across the nation that year would still prove disastrous for many other inner-city communities. It was a moment that has shaped American politics and scarred race relations ever since. The racial issues of the time—more than the response to abortion—likely even helped precipitate the rise of the Religious Right, which has dramatically impacted the practice of our own religion in this country to the present day. But the story of the Kennedy speech gives us a hopeful example of a different way through all of this: something touched that small group of political activists that night. Those few thousand in attendance took his words home with them—they reflected, perhaps prayed, and mourned, and slept. And somehow, their righteous rage and bitter grief was transformed, so that they chose not to rain fire down upon their own city, but instead to follow the much less emotionally satisfying way of justice, which always leads through love. I like to think that, as Aeschylus put it, as they slept that night—in their despair, against their will, wisdom came to those mourning souls, “through the awful grace of God.”

In the months since November 8th, calls for hyper-vigilance and ever-greater political engagement have enveloped the left like a nauseating chorus. Just within the last few days, I’ve come across these examples of such language in random articles or posts on my newsfeed:

- Every moment is an organizing opportunity, every person a potential activist, every minute a chance to change the world. – Julie Felner

- Activism is the rent I pay for living on the planet. – Alice Walker

- [T]he deadliest foe of democracy is sullen, despairing apathy. – The Economist

- Wake up and free your mind. Resist all things that numb you, put you to sleep or help you “cope” with so-called reality. – John W. Whitehead

- Each year during Lent we need to hear once more the voice of the prophets who cry out and trouble our conscience. – Pope Francis

It’s not that I disagree with such talk in principle. It’s just that the constant admonitions to work harder and try harder and push harder don’t help that much. They tend only to add to the exhaustion we all already feel with respect to current events. And yet buried somewhere within all of them is an important truth: we do need to be watchful, to wait on God like bridesmaids in the night. As Christ tells his followers in Luke: “Be dressed for action and have your lamps lit; be like those who are waiting for their master to return from the wedding banquet, so that they may open the door for him as soon as he comes and knocks.”

Ultimately, I’m not saying we should all just go home and chill out, perhaps take a 20-year nap in the Catskills. No, what’s happening around us is not okay. But we must, as Andrew Sullivan recently wrote, seek “a balance between self-preservation and vigilance”, action and contemplation, solitude and fellowship, gregariousness and seriousness, hard conversations and small talk, speaking out and shutting up. The balance between such poles will be different for each of us, but the point remains: We have permission to rest. We cannot fix this. It is in God and through God that we all live and move and have our being. Let us not mistake the call to activism for the call of Christ, though the two sometimes overlap. We do not build the kingdom of God. We seek it, we participate in it, but it is not ours to build, only to serve.

There’s a great quote from Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians: “What then is Apollos? What is Paul? Servants through whom you came to believe… I planted, Apollos watered, but God gave the growth.” It’s a theme echoed by Christ: “This is what the kingdom of God is like. A man scatters seed on the ground. Night and day, whether he sleeps or gets up, the seed sprouts and grows, though he does not know how.”

By all means, if you feel so called, get out there and march, protest, call your representatives, hold their feet to the fire, run for public office. Do what you can. I’ll join you. God uses us in countless ways to plant seeds. But don’t forget: much work is done while we sleep. Rest is its own revolution, a vital space where God has God’s merciful way with our tired and troubled souls, where we let ourselves die that we might live. That, for me, is where real hope lies. Let me leave you with these lines from Meghan O’Rourke:

Before he died, blind and emaciated,

my grandfather, who loved the opera,

told me sometimes

among the tall trees he walked and

listened to the sound

of a river entering the sea

by letting itself be swallowed.

COMMENTS

2 responses to “MLK, Bobby Kennedy, and the Monumental Grace of Sleep”

Leave a Reply

Beautiful, Ben. Sleep is so undertapped, from a religious point of view. Reminds me a little of this:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WcsodwVVxo0

Holy crap! I know this dude! I went to his church in Hamilton, Ontario two weeks ago! Funnily enough, their church service takes place at 3 pm every Sunday… Dude’s on the money.