Elif Batuman takes the title of her first novel, The Idiot, from a Dostoevsky classic. Her young protagonist, Selin, mirrors the innocent Prince Myshkin of the Russian novel. Although an allusion to that giant makes Batuman’s literary ambitions clear, for her sharp narrator, the title may be too self-deprecating. Selin’s a Turkish-American student starting at Harvard with dreams of becoming a writer. From the first pages, we are introduced to her primary writing medium for her early college years: email. Batuman said that when she first finished a draft of the novel in 2001, she had no idea that the email correspondences would give her book a historical feel in 2017. But Selin’s first impressions of communication via the wide web are in fact humorously dated, and the bemused interest she takes to email reflects her approach to the rest of the curious ways of the world. She may be naïve, but she’s no idiot.

Batuman prefaces her novel with a passage from Proust about the life-and-death seriousness of adolescent emotions and the unique spontaneity of that time in our lives: a period that we look back on with overwhelming guilt at first, and then nostalgia. We see these waves of emotion in Selin and the rash actions they sometimes inspire. We also see the formation of something more profound in her: the birth of an artist, perhaps, but most definitively the birth of a self.

Batuman prefaces her novel with a passage from Proust about the life-and-death seriousness of adolescent emotions and the unique spontaneity of that time in our lives: a period that we look back on with overwhelming guilt at first, and then nostalgia. We see these waves of emotion in Selin and the rash actions they sometimes inspire. We also see the formation of something more profound in her: the birth of an artist, perhaps, but most definitively the birth of a self.

In the early sections of the novel, Selin takes us through her first experiences at college. She boldly sets out to make friends and choose the right classes. The reader jumps to conclusions about her best friend, Svetlana, and her love interest, Ivan, but Selin reserves her judgment. She feels what we do about these friends, but she’s innocent of the world’s predilection for types, so she is gracious. Selin is still getting to know herself. While the potential euphoria of an adolescent epiphany is never far off for her, the moments that her evolving self-image could take a hit are also near. For example, an episode as trivial as walking down the street and fielding a snicker from a passerby can force a re-formulation of our self-concepts. What did he/she see in my gait, my clothes, my expression, my soul that garnered such a leer? At a certain age, I imagine, these questions become less important. We know enough of ourselves, or we are stuck so deeply in our ways, that we can’t be shaken from equilibrium. The time, however, when we become aware of other inner lives beyond our own, shakes and unsettles. Here’s a passage from The Idiot with this kind of insight:

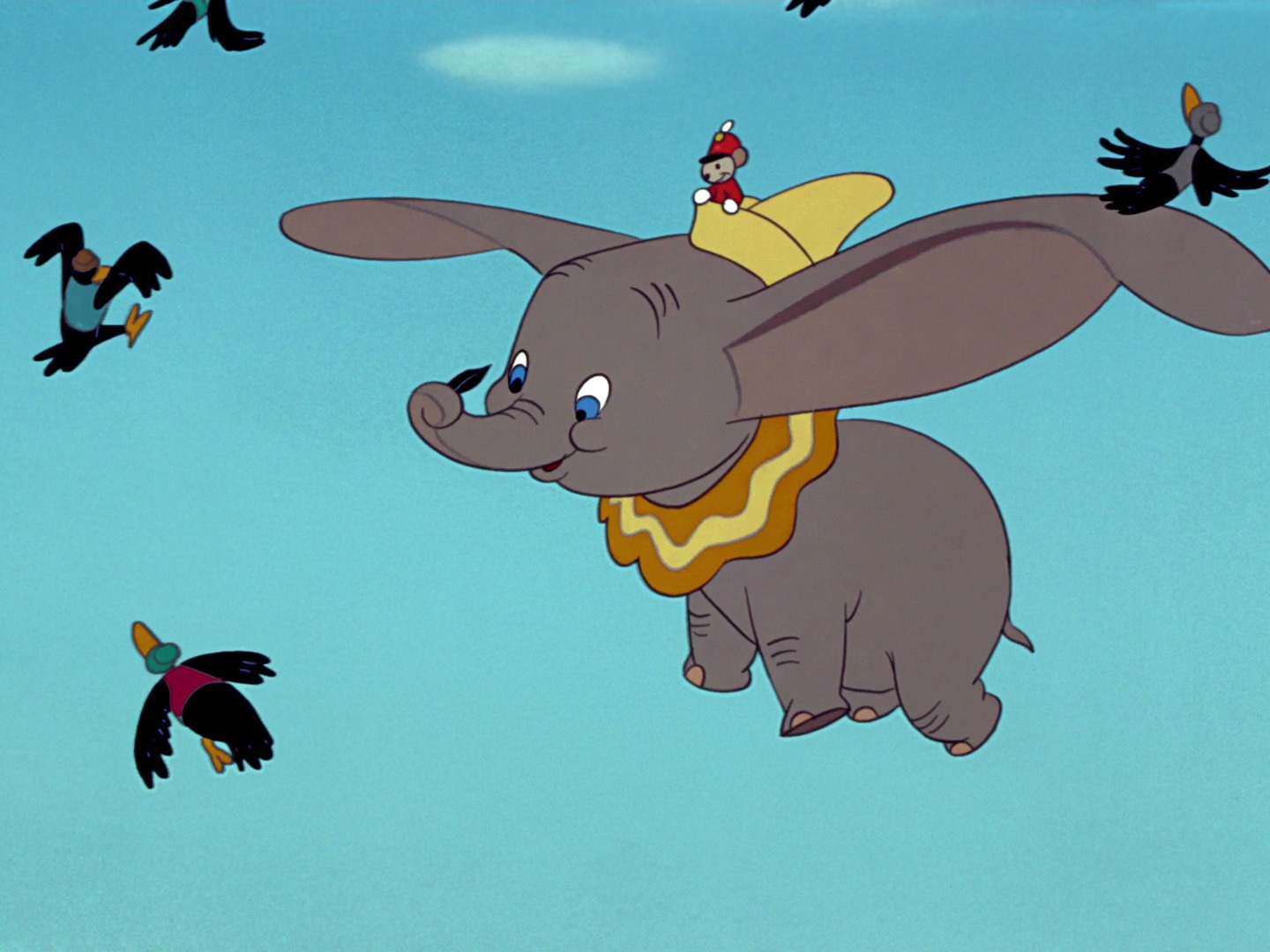

“I found myself remembering the day in kindergarten when the teachers showed us Dumbo, and I realized for the first time that all the kids in the class, even the bullies, rooted for Dumbo, against Dumbo’s tormentors. Invariably they laughed and cheered, both when Dumbo succeeded and when bad things happened to his enemies. But they’re you, I thought to myself. How did they not know? They didn’t know. It was astounding, an astounding truth. Everyone thought they were Dumbo.

Again and again I saw the phenomenon repeated. The meanest girls, the ones who started secret clubs to ostracize the poorly dressed, delighted to see Cinderella triumph over her stepsisters. They rejoiced when the prince kissed her. Evidently, they not only saw themselves as noble and good, but also wanted to love and be loved. Maybe not by anyone and everyone, the way I wanted to be loved. But, for the right person, they were prepared to form a relation based on mutual kindness. This meant that the Disney portrayal of bullies wasn’t accurate, because the Disney bullies realized they were evil, prided themselves on it, loved nobody.”

Selin picks up on the type of self-delusion that sustains us everyday. Thinking we’re the ‘good’ person in a relationship and cordoning ourselves off from the bad people whose sins are unspeakably worse than our own. “Evidently, they not only saw themselves as noble and good, but also wanted to love and be loved.” Who doesn’t? Awareness of this foible of human nature allows Selin to place herself in thoughtful relation to her peers. Beyond the kindergarten classroom and Dumbo, she sees the jockeying of Harvard students, the Hungarian classroom where she teaches for a summer on a grant, and her confounding email threads with Ivan, as the convergence of unique souls. What a message for 2017.

Later, Selin talks to Svetlana on the phone over summer break. Svetlana is a sparkplug; she’s always talking, and she usually has an angle. During the conversation, Selin and her friend, in the manner of tight relationships, set themselves apart from the herd.

“For a while now, I’ve been conscious of a tension in my relationship with you,” Svetlana said. “And I think that’s the reason. It’s because we both make up narratives about our own lives.“

“Everyone makes up narratives about their own lives.”

They continue to go back and forth about the merits of narrative construction. Svetlana wants to affirm her friend, and Selin is characteristically cautious. Their desire to have exceptional news for each other is at once the joy of a close friendship, and a sign of the human need to feel marked, special. It’s a lot like the thirst to love and be loved that Dumbo illuminated for Selin.

Like the Prince of Dostoevsky’s novel, Selin is quick to trust others even when we wish she would be more suspicious. When Batuman leaves her, at the start of her sophomore year, changing her course of study and lamenting the classes and experiences that were a seeming wash, we know there’s more to the story. Selin learned plenty, and we’re happy to have been taught by her.

COMMENTS

2 responses to “The Idiot Redux”

Leave a Reply

Thx, David.

I’m a pilot — Air Kentucky!