Over the past eight years or so, Mockingbird contributors have said quite a lot about the works of Thornton Niven Wilder. His contributions to the idea of a theo-poetic approach to the Gospel, i.e., an approach that avoids didacticism by employing literary archetypes to illustrate gospel themes, are well documented on this site. For a couple of examples, read this from Wilder himself, or this from Paul Zahl. Wilder’s Angel that Troubled the Waters is a tour de force in such terms, and it illustrates what this site is usually trying to do: use an oblique approach to get in past the heart’s defenses, because a didactic frontal assault simply fails every time.

Over the past eight years or so, Mockingbird contributors have said quite a lot about the works of Thornton Niven Wilder. His contributions to the idea of a theo-poetic approach to the Gospel, i.e., an approach that avoids didacticism by employing literary archetypes to illustrate gospel themes, are well documented on this site. For a couple of examples, read this from Wilder himself, or this from Paul Zahl. Wilder’s Angel that Troubled the Waters is a tour de force in such terms, and it illustrates what this site is usually trying to do: use an oblique approach to get in past the heart’s defenses, because a didactic frontal assault simply fails every time.

Nothing has been said thus far, though, about the other Wilder brother, Amos Niven Wilder, who was the chaired professor of New Testament at Harvard Divinity School in the 1950s and 60s. Amos Wilder contributed significantly to the actual thought behind what Thornton Wilder did so elegantly. In truth, Amos Wilder spent much of his career seeking to describe Christianity’s need for such new theo-poetic archetypes as we can see in his brother’s writings.

Consider this quote from his book, Modern Poetry and the Christian Tradition: a study in the relation of Christianity to culture, which was published in 1952. Wilder here describes the state of the modern poetry of his day in the face of a growing religious disbelief:

It will be recalled that Matthew Arnold encouraged the view that poetry could take the place of religion in a significant degree for modern disbelief. With the loss of the biblical faith and other supporting traditions, the modern artist is thrown upon his own psychic resources, and poetry then offers itself as a substitute for or a form of religion. Thus in various forms of mysticism and surrealism, poets elaborate their private mythologies. They exploit the irrational as a means to power. But herein they falsify both poetry and religion…”

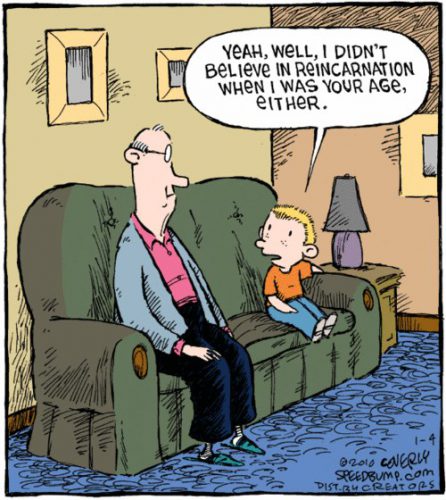

Today, some sixty-five years later, Wilder’s observations could be extended far beyond poetry, to most aspects of the postmodern human condition in terms of both art and life. This brings to mind what UMC Bishop and Duke Divinity School professor Will Willimon once said about preaching the resurrection in a postmodern society. He was at one time worried about trying to convince postmodern skeptics that Jesus was bodily resurrected. Then he realized that, in light of the private mythologies of the postmodern individual, which in the widespread absence of sound biblical preaching and teaching have absorbed so much from Eastern religion and new age mysticism, the real challenge became convincing people that the resurrection happened only once, and that there is no such thing as reincarnation, past lives, and so on. It’s interesting that Wilder was describing so long ago a defect in the modern poetry of his day that could just as easily describe the defective ether in which we now live our day to day lives.

Today, some sixty-five years later, Wilder’s observations could be extended far beyond poetry, to most aspects of the postmodern human condition in terms of both art and life. This brings to mind what UMC Bishop and Duke Divinity School professor Will Willimon once said about preaching the resurrection in a postmodern society. He was at one time worried about trying to convince postmodern skeptics that Jesus was bodily resurrected. Then he realized that, in light of the private mythologies of the postmodern individual, which in the widespread absence of sound biblical preaching and teaching have absorbed so much from Eastern religion and new age mysticism, the real challenge became convincing people that the resurrection happened only once, and that there is no such thing as reincarnation, past lives, and so on. It’s interesting that Wilder was describing so long ago a defect in the modern poetry of his day that could just as easily describe the defective ether in which we now live our day to day lives.

How, then, can we resolve this? How can Christianity reclaim the postmodern mind?

Years later, in the forward to his book Grace Confounding: Poems, Wilder asserted that we must reclaim that place that Willimon described, that inner space in the human psyche that has been invaded by a false mythopoetic, and to do so will require our employment of new and persuasive theo-poetic archetypes as a means of reaching people with the Gospel:

It is in the area of liturgics — the idiom and metaphors of prayer and witness — that the main impasse lies today for the Christian. It is at the level of the imagination that the fateful issues of our new world-experience must first be mastered. It is here that culture and history are broken, and here that the church is polarized. Old words do not reach across the new gulfs, and it is only in vision and oracle that we can chart the unknown and new-name the creatures. Before the message, there must be the vision, before the sermon the hymn, before the prose the poem. Before any new theologies however secular and radical there must be a contemporary theo-poetic.

To me, this describes the work in which we engage here at Mockingbird, in seeking to replace the mythopoetic ether of the so-called inner mythologies of our society with new theo-poetic archetypes that can “reach across the new gulfs” and “new-name the creatures.”

COMMENTS

2 responses to “Naming the Impasse: Amos Niven Wilder and the Religious Imagination”

Leave a Reply

I love this.

These days and times can be no different; humans remain the same, struggling with death and taxes.

Creation growns due to God’s intoned perfection still lacking.

Our trial continues.