This one comes to us from our friend Clayton Hornback.

If there is one thing I cannot claim, it’s the claim of being well-versed in the world of novels and novellas. As much as I hate to admit it, I am a product of our fast-paced, busy, attention-deficit culture. Thus, for my fiction fixes, short-stories have become a saving grace. Recently I’ve been reading a work of short stories by John Steinbeck titled The Long Valley (ironic title for a collection of shorts). Steinbeck is one of my favorite authors, if not the favorite, so I knock out the two birds — reading my favorite author and reading him in short spurts — in one stone. Soli Deo Gloria.

In The Long Valley, the third story is titled “Flight.” “Flight” is about a nineteen-year-old boy named Pepé, who is one of three children to Mama Torres. Pepé is fatherless. His dad died of a rattlesnake bite when Pepé was young. But Pepé’s father left him an inheritance: a switch-blade knife that Pepé was very skilled in throwing, and the knife was “with Pepé always, for it had been his father’s knife.”

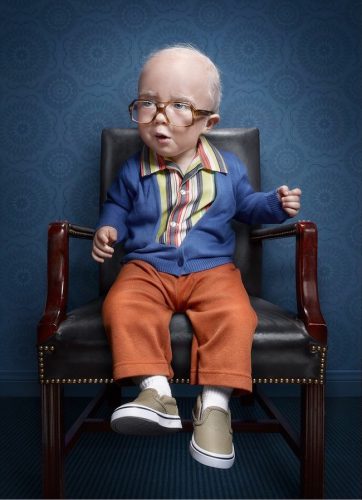

With the absence of his father, Pepé assumes the role of “the man” in the house. He repeatedly tells Mama Torres, “I am a man,” to which she replies, “Thou art a peanut” and “Thou art a foolish chicken” (Moms always have a way with words of affirmation). One of the first adventures of being “a man” comes when Mama Torres tells Pepé to go into Monterrey on a two-day journey to get some medicine for the house. Pepé gladly takes up the call, declaring, “Adios, Mama, I will come back soon. You may send me often alone. I am a man.”

Pepé returns the next day, but when he does, something is different. Steinbeck puts it this way:

Pepé returns the next day, but when he does, something is different. Steinbeck puts it this way:

He was changed. The fragile quality seemed to have gone from his chin. His mouth was less full than it had been, the lines of the lips were straighter, but in his eyes the greatest change had taken place. There was no laughter in them anymore, nor any bashfulness.

Pepé was changed because while he was staying at the house of Mama Torres’ friend, something terrible happened. He tells Mama Torres that a man insulted him, there was a quarrel, and before he knew it, Pepé’s knife had flown and killed the man. Pepé was changed. But one thing hadn’t changed according to Pepé, because he still staunchly declares, “I am a man now.”

Almost immediately, Mama Torres packs Pepé, with rifle, beef jerky, and water, onto a horse and sends him out into the desert wilderness to flee from his pursuers. But while “the man” is out in the desert, things begin to deteriorate rather quickly. Pepé’s pursuers, who throughout the story remain nameless and faceless, catch up to him; he runs out of water; his horse is shot and killed. Pepé is constantly looking over his shoulder, looking for his chasers. Having run out of water, Pepé checks in the bottom of canyon creek beds, only to find waterless, muddy flats. The reader can feel the dryness of Pepé’s throat as he chews on the mud to quench his thirst. Eventually he hears his pursuers again, and he stringently makes his way up to the top of a cliff edge to see if he can take aim with his rifle. He hears the hounds of his pursuers coming up his trail; the time to act is now. Pepé climbs to the top of the ridge peak, stands tall, and Steinbeck concludes:

His body jarred back. His left hand fluttered helplessly toward his breast. The second crash sounded from below. Pepé swung forward and toppled from the rock. His body struck and rolled over and over, starting a little avalanche. And when at last he stopped against a bush, the avalanche slid slowly down and covered up his head.

This story about Pepé stuck with me, mainly because I don’t think I have read anything as illustrative of the law as “Flight.” It begins with a certain, confident, “innocent” boy who declares himself a man, and it ends with a lost, thirsting, wandering “man” who dies buried under desert rocks as a boy.

I am really struck by the story because in reading it I see myself, or for that matter every single person that has ever lived. For Pepé, “manhood” was the law that hung over him, demanding that he achieve. There’s even an audacity in thinking that he had achieved by running Mama Torres’ errand and killing a man. And in every instance, I am Pepé; all are Pepés. Every single day, there are countless laws that demand we achieve, and which at times we think we actually do.

But as law does par excellance, any sense of achievement only feeds the demand and quickens the defeat. Sure, Pepé thinks he has fulfilled the command of “Thou shalt be a man” by running an errand and committing a murder, but just as immediately as that law is seemingly achieved, it comes back bigger and stronger, saying again, “Thou shalt be a man…in the desert.” And eventually, Pepé’s law dehydrates, injures, kills, and crushes him under the avalanche of his attempted achievement. And so it does to each and every one of us.

So, perhaps the next time the law demands achievement, such as Pepé’s “be a man” — perhaps opting for childhood is a good recourse. In fact, it’s the best recourse, for all that can ever be achieved has been by another Man, the right Man on our side, “the man of God’s own choosing. Dost ask who that may be? Christ Jesus, it is he.”

COMMENTS

One response to “Steinbeck and the Flight from the Law”

Leave a Reply

This is powerful stuff. Thank you for posting this.