As we come to the close of a particularly vicious election cycle, we bring out of the archives our “Surviving November” series from four years back. Based on Jonathan Haidt’s work, The Righteous Mind, DZ delves into the moral psychology of political strife, and what hope we might be able to gather in spite of it.

I. Political Divides, Intuitive Dogs, and Rational Tails

Maybe the non-stop and increasingly ludicrous “opposition ads” have started to make you dread turning on the TV. Maybe you can’t read your (predominantly pop culture-focused!) Twitterfeed without getting depressed about the dehumanizing level of partisanship being so casually embraced by otherwise thoughtful people. Maybe you find blind loyalty to (or hatred of) a particular institution fundamentally alienating. Maybe you’ve “hidden” that portion of your friends on Facebook whose political inclinations diverge from your own. Or maybe you’ve lost the ability to sympathize even a little bit with those on “the other side” and have caught yourself characterizing a school of thought or candidate as “insane.” Maybe the across-the-board rage and blame have you seriously questioning the social cost of the Internet (and maybe that makes you nervous, since a big part of your job happens online). Maybe you’re just sick of people pretending that our national discourse hasn’t been hijacked almost entirely by emotional concerns, that all the “arguments” and “facts” and confirmation bias-soaked headlines aren’t just (transparent) vehicles of mutual disdain. Maybe you’re thinking very seriously about sitting this election out, for self-protection if nothing else (and maybe a little despair about human nature). Then again, maybe your cynicism about politicians has become just as cruel and dis-compassionate as anything they might be saying or perpetuating.

Maybe the non-stop and increasingly ludicrous “opposition ads” have started to make you dread turning on the TV. Maybe you can’t read your (predominantly pop culture-focused!) Twitterfeed without getting depressed about the dehumanizing level of partisanship being so casually embraced by otherwise thoughtful people. Maybe you find blind loyalty to (or hatred of) a particular institution fundamentally alienating. Maybe you’ve “hidden” that portion of your friends on Facebook whose political inclinations diverge from your own. Or maybe you’ve lost the ability to sympathize even a little bit with those on “the other side” and have caught yourself characterizing a school of thought or candidate as “insane.” Maybe the across-the-board rage and blame have you seriously questioning the social cost of the Internet (and maybe that makes you nervous, since a big part of your job happens online). Maybe you’re just sick of people pretending that our national discourse hasn’t been hijacked almost entirely by emotional concerns, that all the “arguments” and “facts” and confirmation bias-soaked headlines aren’t just (transparent) vehicles of mutual disdain. Maybe you’re thinking very seriously about sitting this election out, for self-protection if nothing else (and maybe a little despair about human nature). Then again, maybe your cynicism about politicians has become just as cruel and dis-compassionate as anything they might be saying or perpetuating.

Well, if any of the above remotely resonates, do yourself a favor and pick up a copy of Jonathan Haidt’s moral psychology opus, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. I can’t think of a better — or more hopeful — book to help us all, regardless of where we’re coming from, negotiate this weird season. In fact, I think so highly of it that I’ve decided to do a series of posts highlighting some of the main points, this being the first installment.

The Righteous Mind begins with the brilliantly titled section, “The Intuitive Dog and Its Rational Tail,” in which Haidt breaks down some recent research about the mind, specifically how and what drives our moral sensibilities. What is the relationship between reason and emotion, head and heart? We know what Thomas Cranmer would say. We know what David Hume would say. And we probably know what Richard Dawkins would say. Haidt begins from the (Pauline) point of view that the mind is often in conflict with itself, that to be human is “to marvel at your inability to control your own actions” and that human nature is “not just intrinsically moral, it’s also intrinsically moralistic, critical, and judgmental.” In other words, our minds gravitate — by design — toward the concept of “righteousness,” hence the title of the book. To talk about the specific dynamics at play he uses the metaphor of the mind as an elephant and a rider, the elephant being automatic processes such as emotion and the rider being the conscious and controlled ones (the reasoning-why, if you will). Here are a few paragraphs from Haidt on the key distinction between intuition and emotion, taken from pages 43-50:

[What I have] seen in my studies: rapid intuitive judgment (“That’s just wrong!”) followed by slow and sometimes tortuous justifications. The intuition launched the reasoning, but the intuition did not depend on the success or failure of the reasoning … We do moral reasoning not to reconstruct the actual reasons why we ourselves came to a judgment; we reason to find the best possible reasons why somebody else ought to join us in that judgment …

Emotions are not dumb. Emotions are a kind of information processing. Contrasting emotion with cognition is therefore as pointless as contrasting rain with weather, or cars with vehicles … The crucial distinction is really between two different kinds of cognition: intuition and reasoning. Moral emotions are one type of moral intuition, but most moral intuitions are more subtle, they don’t rise to the level of emotions. The next time you read a newspaper or drive a car, notice the many tiny flashes of condemnation that flit through your consciousness. Is each such flash an emotion? … Intuition is the best word to describe the dozens or hundreds of rapid, effortless moral judgements and decisions we all make every day … Intuitions are a kind of cognition. They’re just not a kind of reasoning.

The social intuitionist model offers an explanation of why moral and political arguments are so frustrating: because moral reasons are the tail wagged by the intuitive dog. A dog’s tail wags to communicate. You can’t make a dog happy by forcibly wagging its tail. And you can’t change people’s minds by utterly refuting their arguments … If you want to change people’s minds, you’ve got to talk to their elephants.

Dale Carnegie was one of the greatest elephant-whisperers of all time. In his classic book How to Win Friends and Influence People, Carnegie repeatedly urged readers to avoid direct confrontations. Instead he advised people to “begin in a friendly way,” to “smile,” to “be a good listener,” and to “never say ‘you’re wrong.'” The persuader’s goal should be to convey respect, warmth, and an openness to dialogue before stating one’s own case … You might think his techniques are superficial and manipulative, appropriate only for salespeople. But Carnegie was in fact a brilliant moral psychologist who grasped one of the deepest truths about conflict. He used a quotation from Henry Ford to express it: “If there is any one secret of success it lies in the ability to get the other person’s point of view and see things from their angle as well as your own.”

It’s such an obvious point, yet few of us apply it in moral and political arguments because our righteous minds so readily shift into combat mode. The rider and the elephant work together smoothly to fend off attacks and lob rhetorical grenades of our own. The performance may impress our friend and show allies that we are committed members of the team, but no matter how good our logic, it’s not going to change the minds of our opponents if they are in combat mode too. If you really want to change someone’s mind on a moral or political [ed. note: or theological!] matter, you’ll need to see things from that person’s angle as well as your own. And if you do truly see it the other person’s way — deeply and intuitively — you might even find your own mind opening in response. Empathy is an antidote to righteousness, although it’s very difficult to empathize across a moral divide …

If you ask people to believe something that violates their intuition, they will devote their efforts to finding an escape hatch — a reason to doubt your argument or conclusion. They will almost always succeed.

If this sounds like a rather bleak (and strikingly Reformational) take on human autonomy, that’s because it is. But it’s far from a nihilistic one! Haidt is trying to establish a more humane, patient, and compassionate basis for talking about moral, political, and, yes, theological differences. A slightly less automated mode of communication, if you will. Unless we understand the elaborate defenses and self-justifying mechanisms of the human mind, we will not be able to engage the human heart — and this applies to ourselves as much as those around us. Which means that any discussion of divisive issues must begin from a place of universal limitation, our own most of all. In this light, perhaps it is no surprise that Jesus rarely spoke in naked assertions. Or that those whose moral intuitions his grace transgressed, AKA all of us, reacted so viscerally and violently. It certainly puts our scapegoat-happy zeitgeist in perspective. In fact, speaking of scapegoats, I’ve been told he knew a thing or two about them. (He said … confirming his previously held intuition …)

II. (Inner) Lawyers, (Inner) Press Secretaries, and Presidential Debates

When it comes to The Righteous Mind, political debates pretty much provide an Exhibit A situation. That is, for all the learning and sophistication and charisma up on that stage, when two “righteous minds” are locked in what Haidt calls “combat mode,” autopilot takes over, and you can almost write the script. Yet we all pretty much know that the script itself is not the point of these things — people respond much more to how things are said than what is said. “Do I like this person? Do I trust them?” is the more relevant question than “Do I agree with their arguments? Do I think they’re right?” And maybe those two things are one and the same, who knows. When Haidt talks in the section below about how we care more about the appearance of truth than truth itself, this is part of what he means.

So public debate may be a charade, but it’s still a useful one. Meaning, two people may be talking to each other, but they’re not really talking to each other — nor, truthfully, do any of us expect them to. The notion that one person might concede a point — “you know, I’ve never thought about it that way” — is absurd. The parties are not there to convince one another — duh! — they’re there to convince you and me. We get to watch them in a high-pressure environment, see how they do “on their feet”; we get a sense of their style and personality (not surprisingly, most of the commentary afterward has to do with feeling, not content). It’s a spectator sport, in other words, and we all understand it that way.

So public debate may be a charade, but it’s still a useful one. Meaning, two people may be talking to each other, but they’re not really talking to each other — nor, truthfully, do any of us expect them to. The notion that one person might concede a point — “you know, I’ve never thought about it that way” — is absurd. The parties are not there to convince one another — duh! — they’re there to convince you and me. We get to watch them in a high-pressure environment, see how they do “on their feet”; we get a sense of their style and personality (not surprisingly, most of the commentary afterward has to do with feeling, not content). It’s a spectator sport, in other words, and we all understand it that way.

So we may talk about “winners” and “losers,” but those tend to be pretty arbitrary labels. People hear what they want to hear, myself included. If you don’t like what a certain person represents, you will devote your intellectual energy to poking holes in their statements — before they open their mouths. This isn’t to say that what the candidates are talking about isn’t important — far from it — just that the oppositional format highlights the limits and true purpose of reason. In most settings, reason is confirmatory rather than exploratory. It is the servant of self-justification and, ultimately, self-regard.

None of these insights are particularly fresh, of course. I remember in the early days of Mockingbird, we decided to host a mini-“discussion” with some guys down the street (the fact that it’s almost always guys who buy into the utility of this stuff should be a red flag, btw) on such non-divisive issues as the nature of Christian sanctification and the role of the Law in the life of a believer. The evening wasn’t a bust. We got our blood pumping, and it brought “our side” closer together. We were able to air some grievances and take the arguments in our heads for a spin in a flesh-and-bone setting. But one thing it didn’t do was to convince anyone of anything they didn’t already believe. It was the last time we tried such an event, either in person or online (which is far more vicious).

I’m not trying to say that propositional truth isn’t important. People’s minds are changed — Lord knows mine has been — and it often has to do with hearing someone else’s point of view persuasively presented. But when the brain goes into “combat mode,” when we become over-identified with a particular ideology, justification becomes the name of the game — yes, even when “justification” is the issue at hand! Maybe even especially then. While I’m not sure I’d go as far as Francis Spufford does, I do think he’s onto something, and the election season has only, um, confirmed that hunch. But enough from me. Haidt says it all much better and with far more authority (not that he’ll convince you!). These excerpts are from chapter 4, pg 72-81:

Plato had a coherent set of beliefs about human nature, and at the core of these beliefs was his faith in the perfectability of reason. Reason is our original nature, he thought; it was given to us by the gods and installed in our spherical heads. Passions often corrupt reason, but if we can learn to control those passions, our God-given rationality will shine forth and guide us to do the right thing, not the popular thing.

As is often the case in moral psychology, arguments about what we ought to do depend upon assumptions — often unstated — about human nature and human psychology. And for Plato, the assumed psychology is just plain wrong … Reason is not fit to rule; it was designed to seek justification, not truth … Glaucon was right: people care a great deal more about appearance and reputation than about reality …

If you see one hundred insects working together toward a common goal, it’s a sure bet they’re siblings. But when you see one hundred people working on a construction site or marching off to war, you’d be astonished if they all turned out to be members of one large family. Human beings are the world champions of cooperation beyond kinship, and we do it in large part by creating systems of formal and informal accountability. We’re really good at holding others accountable for their actions, and we’re really skilled at navigating through a world in which others hold us accountable for our own.

Phil Tetlock, a leading researcher in the study of accountability, defines accountability as the “explicit expectation that one will be called upon to justify one’s beliefs, feelings, or actions to others,” coupled with an expectation that people will reward or punish us based on how well we justify ourselves … Accountability pressures increase confirmatory thought. People are trying harder to look right than to be right. Tetlock summarizes it like this:

A central function of thought is making sure that one acts in ways that can be persuasively justified or excused to others. Indeed, the process of considering the justifiability of one’s choices may be so prevalent that decision makers not only search for convincing reasons to make a choice when they must explain that choice to others, the search for reasons to convince themselves that they have made the “right” choice.

Tetlock concludes that conscious reasoning is carried out largely for the purpose of persuasion, rather than discovery. But Tetlock adds that we are also trying to persuade ourselves … Our moral thinking is much more like a politician searching for votes than a scientist searching for truth.

Ed Koch, the brash mayor of New York City in the 1980s, was famous for greeting constituents with the question “How’m I doin’?” It was a humorous reversal of the usual New York “How you doin’?” but it conveyed the chronic concern of elected officials. Few of us will ever run for office, yet most of the people we meet belong to one or more constituencies that we want to win over. Research on self-esteem suggests that we are all unconsciously asking Koch’s question every day, in almost every encounter.

If you want to see post hoc reasoning in action, just watch the press secretary of a president or prime minister take questions from reporters. No matter how bad the policy, the secretary will find some way to praise or defend it. Reporters then challenge assertions and bring up contradictory quotes from the politician, or even quotes straight from the press secretary on previous days. Sometimes you’ll hear an awkward pause as the secretary searches for the right words, but what you’ll never hear is: “Hey, that’s a great point! Maybe we should rethink this policy.”

Press secretaries can’t say that because they have no power to make or revise policy. They’re told what the policy is, and their job is to find evidence and arguments that will justify the policy to the public. And that’s one of the rider’s main jobs: to be the full-time in-house press secretary for the elephant…

People are quite good at challenging statements made by other people, but if it’s your belief, then it’s your possession — your child, almost — and you want to protect it, not challenge it and risk losing it… This is the sort of bad thinking that a good education should correct, right? Well, consider the findings of another eminent reasoning researcher, David Perkins. Perkins brought people of various ages and education levels into the lab and asked them to think about social issues, such as whether giving schools more money would improve the quality of teaching and learning. He first asked subjects to write down their initial judgment. Then he asked them to think about the issue and write down all the reasons they could think of — on either side — that were relevant to reaching a final answer. After they were done, Perkins scored each reason subjects wrote as either a “my-side” argument or an “other-side” argument. Not surprisingly, people came up with many more “my-side” arguments than “other-side” arguments. Also not surprisingly, the more education subjects had, the more reasons they came up with … Perkins found that IQ was by far the biggest predictor of how well people argued, but it predicted only the number of my-side arguments. Smart people make really good lawyers and press secretaries, but they are no better than others at finding reasons on the other side.

This is how the press secretary works on trivial issues where there is no motivation to support one side or the other. If thinking is confirmatory rather than exploratory in these dry and easy cases, then what chance is there that people will think in an open-minded, exploratory way when self-interest, social identity, and strong emotions make them want or even need to reach a preordained conclusion?

This is a profoundly sobering take on human nature. But again, it is far from a hopeless one, especially when it comes to the New Testament (and/or the Protestant Reformation), which paints a very similar anthropological picture, of human beings (religious and non-) consumed with personal justification and righteousness. A search which is so addicting, both consciously and unconsciously, that it co-opts a tragic number of our relationships and pursuits, and is frequently found to be the root of alienation and hurt.

Yet this isn’t so much an occasion for cynicism as compassion. The notion that those who are most violently and adamantly opposed to our particular school of thought are bound by the same desperate psycho-spiritual needs as we are — that they are just expressing themselves in a polar opposite way — might help us love the “other side” a bit more, no? We might even be able to watch the next debate without having to leave the room. Maybe …

Justification and righteousness are not the only things in life, of course. But they are a much bigger part of our day-to-day existence than most of us would like to acknowledge. In fact, I’ve even heard tell of those who are so driven by a need for confirmation that they take captive every corner of culture and thought imaginable — from the music of Axl Rose to the poetry of Emily Dickinson — to their peculiar religious point of view … Wait a second.

Giving this search the essential place in the human make-up it deserves, though, makes the announcement that “we have been justified through faith, [and therefore] we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ” good news, indeed (Rom 5:1). Not only that, but it casts the claim that Christ is not merely full of truth, or the appearance of truth, but that he is Truth itself, as incredibly refreshing and hopeful. Unlike us, he is more interested in reality than in the appearance of it, in those who have ears to hear hearing, rather than wasting time arguing with those who have already made up their minds (Mt 25:29).

Yet even those of us who find ourselves powerless against the tide of internal and external debate (and caught up in the unrest and anger it produces) — whether it be with a political party, a particular candidate, a family member, or a long-dead theologian — are not left comfortless. He came for the sick, after all. For those of us who can’t “lay down our weary tune,” as the Bard wisely commends us to do, Christ laid it down for us … But there I go again, way over my two minutes.

III. Fact Checkers, Missing Ethics Books, and the Must/Can Distinction

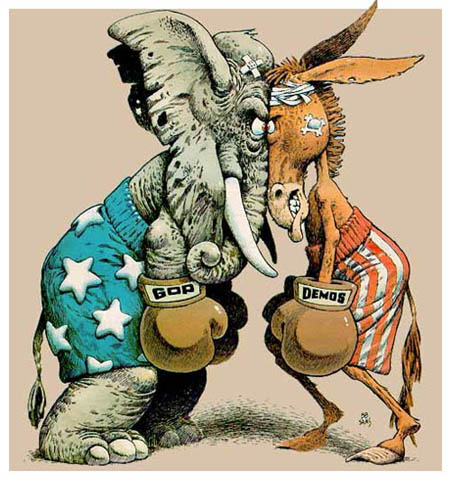

The 2012 election brought us an increase in talk about “fact-checkers.” No doubt will we escape articles and tweets about post-debate/-speech tallies of “checked facts.” While no doubt we could use a little help wading through all campaign hyperbole and Wiki-what-have-you, it sometimes seems that we’ve forgotten the time-tested cliche that one man’s fact is another man’s fiction (and always has been). It may be a cynical sentiment but it is also one that strikes me as far less cynical than the apparently widely held conviction that one or both candidates is an unremorseful liar, foisting their contempt for raw data on an unsuspecting public. The truth is, and I’m convinced we all know this on some level, what unites the two candidates is their incredible ability to see the same facts as evidence of conflicting ideologies. Their steadfast loyalty to the facts as they read them, you might say. This isn’t to suggest there’s no such thing as “hard numbers”–of course there are!–just that no one anywhere has ever been able to engage with those numbers non-emotionally, checking(!) their intuitions at the door. I know this because I do it all the time, and so do you. It’s part and parcel of our identity as fallen men and women: we are inveterate and inveterately lousy fact checkers.

The 2012 election brought us an increase in talk about “fact-checkers.” No doubt will we escape articles and tweets about post-debate/-speech tallies of “checked facts.” While no doubt we could use a little help wading through all campaign hyperbole and Wiki-what-have-you, it sometimes seems that we’ve forgotten the time-tested cliche that one man’s fact is another man’s fiction (and always has been). It may be a cynical sentiment but it is also one that strikes me as far less cynical than the apparently widely held conviction that one or both candidates is an unremorseful liar, foisting their contempt for raw data on an unsuspecting public. The truth is, and I’m convinced we all know this on some level, what unites the two candidates is their incredible ability to see the same facts as evidence of conflicting ideologies. Their steadfast loyalty to the facts as they read them, you might say. This isn’t to suggest there’s no such thing as “hard numbers”–of course there are!–just that no one anywhere has ever been able to engage with those numbers non-emotionally, checking(!) their intuitions at the door. I know this because I do it all the time, and so do you. It’s part and parcel of our identity as fallen men and women: we are inveterate and inveterately lousy fact checkers.

On that note, here we go with part three of our four part series on Jonathan Haidt’s marvelous The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. In part one, we introduced Haidt’s central argument, that when it comes to politics–and reason in general–intuitions come first and strategic reasoning second. We are not ideological “free agents” during election season; we are all deeply identified with a particular set of intuitions that expresses itself in all sorts of self-justifying ways. In part two, we took a closer look at the role of reason in this light, how the primary (but not exclusive!) purpose of strategic reasoning is confirmatory rather than exploratory, and how the debate culture bears this out, to say nothing of our personal relationships. We even made the bold claim that human beings care more about appearance than truth. (Given the nature of this approach, it should come as no surprise that Haidt has provoked such a reaction from certain heavily invested quarters.)

This time we’ll delve a little deeper into the mechanics of how we are able to pull off this political self-justification with such consistency and creativity. And to do so, we need to look at one of the most closet Lutheran sections in the entire book, almost laughably so, in which Haidt unpacks the Must/Can distinction:

When my son, Max, was three years old, I discovered that he’s allergic to ‘must’. When I would tell him that he must get dressed so that we can go to school (and he loved to go to school), he’d scowl and whine. The word must is a little verbal handcuff that triggered in him the desire to squirm free.

The word ‘can’ is so much nicer: “can you get dressed, so that we can go to school?” To be certain that these two words were really night and day, I tried a little experiment. After dinner one night, I said “Max, you must eat ice cream now.”

“But I don’t want to!”

Four seconds later: “Max, you can have ice cream if you want.”

“I want some!”

The difference between Can and Must is the key to understanding the profound effects of self-interest on reasoning. It’s also the key to understanding many of the strangest beliefs-in UFO abductions, quack medical treatments, and conspiracy theories.

The social psychologist Tom Gilovich studies the cognitive mechanisms of strange beliefs. His simple formulation is that when we want to believe something, we ask ourselves, “Can I believe it?” Then, we search for supporting evidence, and if we find even a single piece of pseudo-evidence, we can stop thinking. We now have permission to believe. We have a justification, in case anyone asks.

In contrast, when we don’t want to believe something, we ask ourselves “Must I believe it?” Then we search for contrary evidence, and if we find a single reason to doubt the claim, we can dismiss it. You only need one key to unlock the handcuffs of must.

Psychologists now have file cabinets full of findings on “motivated reasoning,” showing the many tricks people use to reach the conclusions they want to reach. When subjects are told that an intelligence test gave them a low score, they choose to read articles criticizing (rather than supporting) the validity of IQ tests. When people read a (fictitious) scientific study that reports a link between caffeine consumption and breast cancer, women who are heavy coffee drinkers find more flaws in the study than do men and less caffeinated women…

The difference between a mind asking “Must I believe it?” versus “Can I believe it?” is so profound that it even influences visual perception. Subjects who thought they’d get something good if a computer flashed up a letter than a number were more likely to see the ambiguous figure to the right as the letter B, rather than the number 13.

If people can literally see what they want to see–given a bit of ambiguity–is it any wonder that scientific studies often fail to persuade the general public? Scientists are really good at finding flaws in studies that contradict their own views, but it sometimes happens that evidence accumulates across many studies to the point where scientists must change their minds. I’ve seen this happen in my colleagues (and myself) many times, and it’s part of the accountability system of science–you’d look foolish clinging to discredited theories. But for nonscientists, there is no such thing as a study you must believe. It’s always possible to question the methods, find an alternative interpretation of the data, or, if all else fails, question the honesty or ideology of the researchers.

As always – and this is almost certainly my own confirmation biases talking – these findings are soaked in the reality of Original Sin, what GK Chesterton so brilliantly referred to as the only “empirically verifiable doctrine” (the facts are in!). You and I are in a very real sense captive to intuitions that are outside of our control, and like the God-complex junkies that we are, we will bend the world to fit our understanding of it. That is, “must” may be a handcuff, but the unceasing compulsion to fashion cardboard keys, is the real ball and chain. We insist on being the final arbiters of truth and meaning–not anyone else–certainly not God. We see what we want to see; we hear what we want to hear; we believe what we want to believe, and at no point is this more blatant than during a presidential election season. The illusion of objectivity is just that: an illusion. Perhaps this is the intellectual aspect of what St Paul meant when he wrote about being “slaves to sin”. But again, this is not reason to despair. The God of the Bible is concerned with those who are stuck–emotionally, intellectually, spiritually–in webs of their own making. Which is everyone. Truth, to the extent that it can be known, is revealed to us, not by us. Now comes the jaw-dropping part:

As always – and this is almost certainly my own confirmation biases talking – these findings are soaked in the reality of Original Sin, what GK Chesterton so brilliantly referred to as the only “empirically verifiable doctrine” (the facts are in!). You and I are in a very real sense captive to intuitions that are outside of our control, and like the God-complex junkies that we are, we will bend the world to fit our understanding of it. That is, “must” may be a handcuff, but the unceasing compulsion to fashion cardboard keys, is the real ball and chain. We insist on being the final arbiters of truth and meaning–not anyone else–certainly not God. We see what we want to see; we hear what we want to hear; we believe what we want to believe, and at no point is this more blatant than during a presidential election season. The illusion of objectivity is just that: an illusion. Perhaps this is the intellectual aspect of what St Paul meant when he wrote about being “slaves to sin”. But again, this is not reason to despair. The God of the Bible is concerned with those who are stuck–emotionally, intellectually, spiritually–in webs of their own making. Which is everyone. Truth, to the extent that it can be known, is revealed to us, not by us. Now comes the jaw-dropping part:

Webster’s Third New International Dictionary defines “delusion” as “a false conception and persistent belief unconquerable by reason in something that has no existence in fact.” As an intuitionist, I’d say that the worship of reason is itself an illustration of one of the most long-lived delusions in Western history: the rationalist delusion. It’s the idea that reasoning is our most noble attribute, one that makes us like the the gods (for Plato) or that brings us beyond the “delusion” of believing in gods (for the New Atheists). The rationalist delusion is not just a claim about human nature. It’s also a claim that the rational caste (philosophers or scientist) should have more power, and it usually comes along with a utopian program for raising more rational children.

From Plato through Kant and Kohlberg, many rationalists have asserted that the ability to reason well about ethical issues causes good behavior. They believe that reasoning is the royal road to moral truth, and they believe that people who reason well are more likely to act morally.

But if that were the case, then moral philosophers–who reason about ethical principles all day long–should be more virtuous than other people. Are they? The philosopher Eric Schweitzgebel tried to find out. He used surveys and more surreptitious methods to measure how often moral philosophers give to charity, vote, call their mothers, donate blood, donate organs, clean up after themselves at philosophy conferences, and respond to emails purportedly from students. And in none of these ways are moral philosophers better than other philosophers or professors in other fields.

Schwitzgebel even scrounged up the missing-book lists from dozens of libraries and found that academic books on ethics, which are presumably borrowed mostly by ethicists, are more likely to be stolen or just never returned than books in other areas of philosophy. In other words, expertise in moral reasoning does not seem to improve moral behavior, and it might even make it worse.

Haidt is almost paraphrasing St. Paul when he talks about how “knowledge puffs up, but love builds up” (1 Cor 8:1). Information and self-knowledge, regardless of how reliable, may have all sorts of uses, but on their own, it is not enough to change a person or their behavior (seldom even their mind). Preachers know this–at least, the good ones do. There’s a difference between a sermon and a lecture, after all. And there’s a huge difference between information about God and God himself. The example of the missing ethics library books is about as perfect an example of this reality as one could fine. That is, formal expertise on the subject of right-doing has not created more upstanding citizens; it has merely made people better at justifying their actions.

Perhaps this is just another long-winded way of saying that ‘justification’ is not just some boutique theological abstraction; it lies behind an embarrassing amount of our daily stress, striving, and divisions. So where’s the hope? Ultimately, it’s in the one who justifies the ungodly of course. But maybe there’s a present-tense upside as well. Having identified our own curved-in interaction with politics and politicians, we may find that we’re marginally more patient with the ideological autopilot in ourselves and others, an empathy that *might* help us take the facts on their own terms a bit more easily, or at least allow us to… survive November.

IV. Partisan Narratives (and Cruel Choirmasters)

Living in a “swing battleground state” (VA), I get the privilege of witnessing the escalation of hostilities from a front row seat every election season. And escalate they do! From the ads on TV to the volunteers at the door, the signs on the street to the telemarketers on the phone, it’ll be hard to hide come November. Last time around, apparently even Walking Dead viewers were on the fence (Arrow viewers, not so much).

There’s obviously an important place in a presidential race for indignation and culpability, anger and blame, etc. The permanence of the logs in our own eyes does not somehow invalidate the specks in eyes of others, as it were. But it’s not the vocal dissatisfaction and criticism that get me down; it’s the thinly veiled contempt, the very real suspicion that certain people are wearing horns, the sense that if one of the candidates got hit by a bus, some people would be genuinely happy about it. And it’s just as pronounced on talk radio as it is on Slate.com. This is nothing new of course; what I’m talking about here is not “the issues” themselves as much as what’s driving the emotions that make it so difficult to discuss those issues.

There’s obviously an important place in a presidential race for indignation and culpability, anger and blame, etc. The permanence of the logs in our own eyes does not somehow invalidate the specks in eyes of others, as it were. But it’s not the vocal dissatisfaction and criticism that get me down; it’s the thinly veiled contempt, the very real suspicion that certain people are wearing horns, the sense that if one of the candidates got hit by a bus, some people would be genuinely happy about it. And it’s just as pronounced on talk radio as it is on Slate.com. This is nothing new of course; what I’m talking about here is not “the issues” themselves as much as what’s driving the emotions that make it so difficult to discuss those issues.

So why do we all hate each other so much? What is at the root of the partisan mindset? When did we become so insanely tribal? Fortunately, there’s a chapter in Jonathan Haidt’s The Righteous Mind (number 12) entitled “Can’t We All Disagree More Constructively?” that more or less seeks to answer these questions directly. The research contained therein burrows deep into the heart of human nature and could not be more relevant to us here.

But first, bear with me for two sentences: As you may recall, Haidt breaks our moral intuitions down into six innate “foundations”: Care, Fairness, Liberty, Loyalty, Authority and Sanctity. He compares them to taste receptors in the tongue, the fancy term being Moral Foundations Theory. Regardless of whether you buy those categories–and they’re far less cut and dry than they might appear (worth reading the book to find out more)–I don’t know how you could disagree with the assessment that the American political landscape has become increasingly polarized.

According to Haidt, the moral foundations that we personally embrace–and every individual is slightly different–are not merely ideological. They all but dictate the carefully-edited narratives we craft for both ourselves (“our life story”) and the world.

“The human mind is a story processor, not a logic processor. Everyone loves a good story; every culture bathes its children in stories. Among the most important stories we know are stories about ourselves… These narratives are not necessarily true stories–they are simplified and selective reconstructions of the past, often connected to an idealized vision of the future. But even though life narratives are to some degree post hoc fabrications, they still influence people’s behavior, relationships, and mental health.

Life narratives are saturated with morality. In one study, McAdams used Moral Foundation Theory to analyze narratives he collected from liberal and conservative Christians. He found the same patterns in these stories that my colleagues and I had found using questionnaires at YourMorals.org:

When asked to account for the development of their own religious faith and moral beliefs, conservatives underscored deep feelings about respect for authority, allegiance to one’s group, and purity of the self, whereas liberals emphasized their deep feelings regarding human suffering and social fairness.

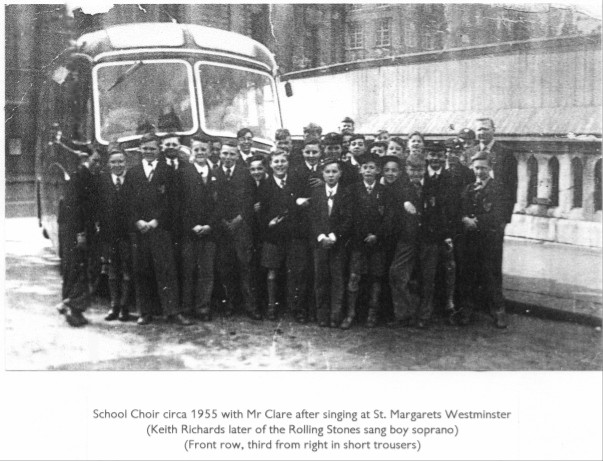

Life narratives provide a bridge between developing adolescent self and an adult political identity. Here, for example, is how Keith Richards describes a turning point in his life in his recent autobiography. Richards, the famously sensation-seeking and nonconforming guitarist of the Rolling Stones, was once a marginally well-behaved member of his school choir. The choir won competitions with other schools, so the choir master got Richards and his friends excused from many classes so that they could travel to ever larger choral events. But when the boys reached puberty and their voices changed, the choir master dumped them. They were then informed that they would have to repeat a full year in school to make up for their missed classes, and the choir master didn’t lift a finger to defend them.

It was a “kick in the guts,” Richards says. It transformed him in ways with obvious political ramifications:

The moment that happened, Spike, Terry and I, we became terrorists. I was so mad, I had a burning desire for revenge. I had reason then to bring down this country and everything it stood far. I spent the next three years trying to [mess] them up. If you want to breed a rebel, that’s the way to do it… It still hasn’t gone out, the fire. That’s when I started to look at the world in a different way, not their way anymore. That’s when I realized that there’s bigger bullies than just bullies. There’s them, the authorities. And a slow-burning fuse was lit.

Richards may have been predisposed by his personality to become a liberal, but his politics were not predestined. Had his teachers treated him differently–or had he simply interpreted events differently when creating early drafts of his narrative–he could have ended up in a more conventional job surrounded by conservative colleagues and sharing their moral matrix. But once Richards came to understand himself as a crusader against abusive authority, there was no way he was ever going to vote for the British Conservative Party. His own life narrative just fit too well with the stories that all parties on the left tell in one form or another.“

At our 2012 Spring Conference, Aaron Zimmerman talked about this same dynamic with piercing insight–the idea that human beings invariably conceive of their lives as some kind of narrative, usually one of progress and improvement or redemption (but sometimes one of shame and self-loathing). You might say we are story addicts and the stories we tell about ourselves essentially function as a Law of who we believe We Must Be or Become, thereby preventing us from seeing reality for what it is. They keep our eyes fixed firmly on our own navels, rather than on God, who is more concerned with who we actually are than with who we insist (to others and to Him) that we must be.

At our 2012 Spring Conference, Aaron Zimmerman talked about this same dynamic with piercing insight–the idea that human beings invariably conceive of their lives as some kind of narrative, usually one of progress and improvement or redemption (but sometimes one of shame and self-loathing). You might say we are story addicts and the stories we tell about ourselves essentially function as a Law of who we believe We Must Be or Become, thereby preventing us from seeing reality for what it is. They keep our eyes fixed firmly on our own navels, rather than on God, who is more concerned with who we actually are than with who we insist (to others and to Him) that we must be.

For example, if your “life narrative” involves you having long since conquered your impatience with a sibling, when you blow up at them over Thanksgiving, you’ll have to rationalize or deny the explosion to keep that narrative intact. Or religiously speaking, when we’ve set our testimony in stone and maybe even built our faith upon some form of improved behavior, we have a hard time making sense of any feelings or actions that don’t fit with it. The development of double lives is almost a foregone conclusion. Haidt is simply saying that these personal narratives inevitably have a moral and therefore political dimension, i.e., that micro narratives very quickly turn into macro ones. The nature of that dimension varies along experiential (and intellectual) lines, but its existence–in some form–does not.

“[The liberal and conservative] narratives are as opposed as could be. Can partisans even understand the story told by the other side? The obstacles to empathy are not symmetrical… Even though conservatives score slightly lower on measures of empathy and may therefore be less moved by a story about suffering and oppression, they can still recognize that it is awful to be kept in chains…

But when liberals try to understand the [conservative] narrative, they have a harder time. When I speak to liberal audiences about Loyalty, Authority and Sanctity, I find that many in the audience don’t just fail to resonate; they actively reject these concerns as immoral. Loyalty to a group shrinks the moral circle; it is the basis of racism and exclusion, they say. Authority is oppression. Sanctity is religious mumbo-jumbo whose only function is to suppress female sexuality and justify homophobia.”

“[In one study we attempted to compare] people’s expectations about “typical” partisans to the actual responses from partisans on the left and the right. Who was best able to pretend to be the other?

The results were clear and consistent. Moderates and conservatives were most accurate in their predictions, whether they were pretending to be liberals or conservatives. Liberals were the least accurate, especially those who described themselves as “very liberal.” The biggest errors in the whole study came when liberals answered the Care and Fairness questions while pretending to be conservatives. When faced with questions such as “one of the worst things a person could do is hurt a defenseless animal” or “justice is the most important requirement for a society,” liberals assumed that conservatives would disagree. [But they didn’t].

If you don’t see that [conservatives are] pursuing positive values of Loyalty, Authority and Sanctity, you almost have to conclude that Republicans see no positive value in Care and Fairness. You might even go so far as Michael Feingold, a theater critic for the liberal newspaper the Village Voice, when he wrote:

Republicans don’t believe in the imagination, partly because so few of them have one, but mostly because it gets in the way of their chosen work, which is to destroy the human race and the planet. Human beings, who have imaginations, can see a recipe for disaster in the making; Republicans, whose goal in life is to profit from disaster and who don’t give a hoot about human beings, either can’t or won’t. Which is why I personally think they should be exterminated before they cause any more harm.

One of the many ironies in this quotation is that it shows the inability of a theater critic–who skillfully enters fantastical imaginary worlds for a living–to imagine that Republicans act within a moral matrix that differs from his own. Morality binds and blinds.”

Again, the point of this post is not somehow to argue that one partisan mindset is better than another (seriously!). The point is simply that the roots of each are tapping into a wellspring as universal as it is subterranean. We are all actively identified with narratives that we have a large stake in being true–even/especially those of us who talk day in and day out about (our) narratives in such terms. The Law is written on the heart; we are hardwired for it. And we know from experience that when these narratives are threatened, be it emotionally, financially, cosmetically, spiritually, etc–when they are shown to be nothing more or less than stories (idols)–we react, and often violently. A Pharisee will do anything he or she can to hold onto their story of spiritual-religious progress, to the point of executing the One who opposes it. Perhaps it should come as no surprise that these findings paint a picture of human beings as both more limited in agency and ingrained with religiosity than the ideologies themselves would. Haidt probably wouldn’t put it that way, but who knows, maybe he would:

“Morality binds and blinds. This is not just something that happens to people on the other side. We all get sucked into tribal moral communities. We circle around sacred values and then share post hoc arguments about why we are so right and they are so wrong. We think the other side is blind to truth, reason, science, and common sense, but in fact everyone goes blind when talking about their sacred objects… If you want to understand another group, follow the sacredness.”

Make no mistake: come November the emotional fallout will be immense. Many a narrative will be under assault. Sacred spaces will have been desecrated. Blood and blame will run high, and millions will project messianic importance onto some poor guy who cannot possibly bear the weight. TLC will be in short supply (as if there wasn’t already enough of a premium on grace in public life).

But nothing about the human propensity for misguided worship and narrative-construction will have changed. Nothing will have changed about the amount of narrative condemnation under which we are all living, which is 100%. Fortunately, neither will have anything changed about the Narrative-That-Isn’t-a-Narrative, the old, old story that doesn’t play in any demographic (never has and never will), the one that no one would have made up to garner favor or get votes, the ole’ wooden cross that can’t be spun no matter how hard it’s pushed. I’m referring to the only story worth retelling: the one about the suffering servant who gave up his power for the sake of inveterate storytellers who are blinded by their morality and bound by their self-justifying DNA.

COMMENTS

6 responses to “Surviving November”

Leave a Reply

Thanks. I definitely needed this. Again.