We’ve all been there. You say something to a friend or family member or spouse that seems innocuous. “Have you seen my sunglasses?”. “I may have to postpone our lunch.” Or maybe you do something thoughtless but minor. You forget to return an email. You borrow a piece of clothing without asking. The response you get is vicious–way out of proportion with whatever you’ve said or done.

This happens with alarming frequency in relationships, especially romantic ones. Soon both parties have shifted into “combat mode” and the conflict has escalated to painful heights. Your action or comment has triggered something significant in the other party, what psychologists call “a reaction formation”, usually having to do with their past. Sometimes, after you’ve both cooled down, the overreacting half says something like, “I’m sorry. The last person I dated cheated on me, and I think it’s made me oversuspicious and accusatory.” Or “when we were younger, my brother used to always take my things without asking, and it made me feel really disrespected.” In our parlance, your remark or action has pushed on some past verdict or wound. The other person heard the Law where it wasn’t intended.

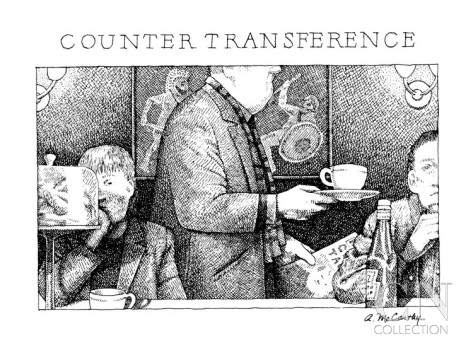

We’re talking here about Transference, something that’s absolutely crucial for anyone involved in the task of loving another person to understand. It may be even more critical for those involved in the helping professions, especially the ministry.

At its base, transference implies an obvious truth: that all of us bring emotional/spiritual/relational baggage with us wherever we go, often in the form of unconscious associations. These associations are so strong that they lead us to replay past injustices or hurts with fresh actors–usually without their consent or awareness.

At its base, transference implies an obvious truth: that all of us bring emotional/spiritual/relational baggage with us wherever we go, often in the form of unconscious associations. These associations are so strong that they lead us to replay past injustices or hurts with fresh actors–usually without their consent or awareness.

Transference can be the key to incredible healing. Psychotherapy is pretty much premised on the idea. A good counselor (or pastor) can serve as a stand-in/proxy for a dead parent or estranged child, someone in whose presence you can express the things you never were able to in person, etc. An agent of grace in other words.

Of course, transference can also be a driver of burnout and exhaustion. I remember speaking to someone at a dinner party who told me they had recently tried going back to church after a long time away. The pastor was nice, the congregation seemed warm, the sermons were surprisingly good. But she found that the building–not the one she grew up in–brought back too many awful memories. She found herself having hateful thoughts about the people in the pews and misinterpreting every kind gesture from the staff as a sign of aggression. Eventually she resigned herself to staying away. The transference was too much. She didn’t like herself when she was there and feared she would develop a reputation.

What I wanted to tell her was that, given the baggage that folks tend to have with G-O-D, ministers deal with such “irrational” behavior every Sunday if not every day. It should be part of the ordination vows. “The collar you are about to don will serve as a big red bullseye for transference of sentiment about a parent, deity, and/or institution”. Sometimes that transference is expressed as undue adoration or infatuation but more often in terms of resentment, insecurity and need.

Again, this is a privilege as much as a burden. Yet it does come at a cost, both in terms of the loneliness it can instill (in the person on the receiving end) and the way in which one’s own transferences–or counter-transferences–operate. No one is exempt.

All this by way of introduction to another excerpt from the latest gift-that-keeps-on-giving, Alain de Botton’s The Course of Love. I promise I’ll give it a rest after this. But his chapter on transference may be my favorite, for no other reason than the way he dramatizes it–though you’ll have to pick up the book to read that part. Here I’m interested in reproducing his italicized commentary on the protagonists. Another paean to low anthropology and its counterintuitive effect on love:

The structure looks something like this: an apparently ordinary situation or remark elicits from one member of a couple a reaction that doesn’t seem quite warranted, being unusually full of annoyance or anxiety, irritability or coldness, panic or recrimination. The person on the receiving end is puzzled: after all, it was just a simple request for a loving good-bye, a plate or two left unwashed in the sink, a small joke at the other’s expense or a few minutes’ delay. Why, then, the peculiar and somehow outsized response?

The behavior makes little sense when one tries to understand it according to the current facts. It’s as if some aspect of the present scenario were drawing energy from another source, as it if were unwittingly triggering a pattern of behavior that the other person originally developed long ago in order to meet a particular threat which has now somehow been subconsciously re-evoked. The overreact is responsible, as the psychological term puts it, for the “transference” of an emotion from the past onto someone in the present–who perhaps doesn’t entirely deserve it.

Our minds are, oddly not always good at knowing what era they are in. They jump a little too easily, like an erstwhile victim of burglary who keeps a gun by the bed and is startled awake by every rustle.

What’s worse for the loved ones standing in the vicinity is that people in the throes of a transference have no easy way of knowing, let alone calmly explaining, what they are up to; they simply feel that their response is entirely appropriate to the occasion. Their partners on the other hand may reach a rather different and rather less flattering conclusion: that they are distinctly odd–and maybe even a little mad…

When our minds are involved in transference, we lose the ability to give people and things the benefit of the doubt; we swiftly and anxiously move towards the worst conclusions that the past once mandated.

Unfortunately, to admit that we may be drawing on the confusions of the past to force an interpretation onto what’s happening now seems humbling and not a little humiliating: Surely we know the difference between our partner and a disappointing parent, between a husband’s short delay and a father’s permanent abandonment; between some dirty laundry and a civil war?

The business of repatriating emotions emerges as one of the most delicate and necessary tasks of love. To accept the risks of transference is to prioritize sympathy and understanding over irritation and judgment. Two people can come to see that sudden bursts of anxiety or hostility may not always be directly caused by them, and so should not always be met with fury or wounded pride. Bristling and condemnation can give way to compassion.

We don’t need to be constantly reasonable in order to have good relationships; all we need to have mastered is the occasional capacity to acknowledge with good grace that we may, in one or two areas, be somewhat insane.

Hmmm…. Temporary insanity, overreaction, and lashing out being met not with judgment but patience and compassion, indeed, with that strange brand of reverse transference known as imputation (a disposition grounded in a previous era if ever there was one). I can only hope this holds true for our longest term relationship. You know, with the God who repatriates not just emotions but the heavy-laden failed lovers who feel them.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply