A few months after my wife and I got engaged, an older friend of hers pulled me aside and tried to do me a favor. He told me that if there was anything he wished he could have told his premarital self, it was that, no matter who you marry, they will be coming from the opposite end of the spectrum, culturally speaking. If he had known that up front, it might have spared him and his significant other considerable heartache.

Like much of what people tell you before you get married (or have kids), his words were both 100% true and 100% impossible to understand before taking the plunge. That is to say, I was baffled.

To the outside eye, my wife and I were coming from embarrassingly similar places: both of us grew up in or around big cities on the East Coast (north of the Mason-Dixon) and had been educated in over-regarded liberal arts institutions, we were both baptized in Episcopal churches, both sets of parents were still married, both of us had been raised with siblings of the same sex, and we were both fish out of water (among our peers) on the Jesus question. We enjoyed the same movies and appreciated the same jokes. We weren’t identical, obviously/thankfully, but opposites? No way. We were what people call ‘well-matched’.

And yet, her friend was right. In the life of a marriage, similarities are largely taken for granted. Where you live–and where you get bogged down–are the places of divergence. It doesn’t matter how (ostensibly) minor they may be. Even tiny points of friction will come to occupy disproportionately vast emotional space, so much so that it often feels like you’re coming from 180-degree opposite ‘cultures’. Meaning, you may have 95% of life and outlook in common with your spouse; the 5% is where your relationship is going to take place. Love can only truly enter the picture once affinity ends. In other words, you won’t feel well-matched. At least not when it matters.

These are just a couple of cursory thoughts to introduce the best article I’ve read in The NY Times this year, “Why You Will Marry the Wrong Person” by ‘religious atheist’ extraordinaire, Alain de Botton. Alain is in the midst of promoting his new novel, The Course of Love, and suffice it to say, after reading the op-ed, “Add to Cart” was my next step. (Loyal readers will notice quite a bit of overlap with previous posts on the Soulmate Mandate).

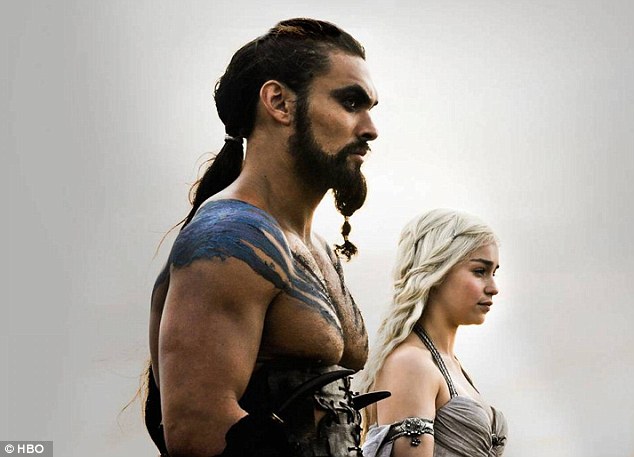

De Botton spends the first half of the column tracing the historical shift in our thinking about marriage, from a joining-together based on reason (economic, political, logistical–think GoT) to one based on sentiment:

What matters in the marriage of feeling is that two people are drawn to each other by an overwhelming instinct and know in their hearts that it is right… The prestige of instinct is the traumatized reaction against too many centuries of unreasonable reason.

Makes perfect sense. Yet as mechanical and cruel as the reason model often was (see: Western Literature), the new model has not proven to be without significant drawbacks, a few of which de Botton goes on to enumerate. For example, not only are our affections fundamentally fickle, they are often shaped by the wounds and vicissitudes of childhood, which tend to lead us away from health and happiness rather than toward it (i.e., the ever popular dichotomy between what we want vs. what we need).

Furthermore, loneliness is such a powerful force (and feeling!) that it often clouds our judgment, setting us up for co-dependence and failure just as much as fruitful companionship.

But the primary drawback de Botton hones in on is the way that marriages of feeling operate as arrangements of mutual (emotional) self-fulfillment. It’s not so much that “you are the one for them” but that “they are the one for you.” Such relationships thrive, consciously or not, on illusion/projection vis-a-vis the other person. They can’t not. As we’re fond of saying, expectation is a planned resentment, and there are no greater expectations than the astronomic ones we foist on a potential (soul)mate. Whoever you marry within such a framework will be the wrong person simply by virtue of them being a person. Law, in this regard, kills love.

Fortunately, that’s not (always) the end of the story:

The good news is that it doesn’t matter if we find we have married the wrong person.

We mustn’t abandon him or her, only the founding Romantic idea upon which the Western understanding of marriage has been based the last 250 years: that a perfect being exists who can meet all our needs and satisfy our every yearning.

We need to swap the Romantic view for a tragic (and at points comedic) awareness that every human will frustrate, anger, annoy, madden and disappoint us — and we will (without any malice) do the same to them. There can be no end to our sense of emptiness and incompleteness. But none of this is unusual or grounds for divorce. Choosing whom to commit ourselves to is merely a case of identifying which particular variety of suffering we would most like to sacrifice ourselves for.

This philosophy of pessimism offers a solution to a lot of distress and agitation around marriage. It might sound odd, but pessimism relieves the excessive imaginative pressure that our romantic culture places upon marriage. The failure of one particular partner to save us from our grief and melancholy is not an argument against that person and no sign that a union deserves to fail or be upgraded.

The person who is best suited to us is not the person who shares our every taste (he or she doesn’t exist), but the person who can negotiate differences in taste intelligently — the person who is good at disagreement. Rather than some notional idea of perfect complementarity, it is the capacity to tolerate differences with generosity that is the true marker of the “not overly wrong” person. Compatibility is an achievement of love; it must not be its precondition.

Where Alain uses the word “pessimism” we might sub in “original sin” or “low anthropology” but the end point is the same. Optimism doesn’t foster hope, it shortcircuits it. Love must have something other than emotional fulfillment at its fulcrum for it to abide.

You might say, then, that along with de Botton, we do not embrace a sober understanding of human nature/capability in order to protect or exonerate ourselves, or even because it’s ‘true’ (though it is). We do so first and foremost for its effect on love–AKA the only force in the universe that actually has the power to lift the human spirit out of its crippled inwardness.

De Botton seems all too aware that the humanism espoused by his co-constituents in the TED-o-sphere frequently entails a set of inflated expectations, species-wise. Expectations that are not merely unrealistic and hubristic but actively counterproductive and lonely-making. Conversely, he has the chutzpah to claim that what looks like a tragic view of life is actually a starting point for compassion, forgiveness, and joy. Maybe even lasting romance.

Sadly, Alain cannot go beyond the horizontal. I wish he could. He might find in the vertical a third model for marriage, not one of expediency or mutual gratification but divestment and sacrifice: the groom who gives himself fully for his wayward bride, the sign of his fidelity being not a ring but a cross. This groom is under no illusions about what he’s getting/gotten himself into. Those have been stripped away. He isn’t waiting for you and me to get our relationships–or feelings–right in order to leverage his devotion. In fact, he stands ready to absolve us of them. He knows that “the wrong people” are all there are, that none of us are very good at loving or being loved. Yet he refuses to spare himself the heartache, thank God.

Perhaps because he is the opposite end of the cultural spectrum incarnate, and not even death can do us part. L’chaim!

An expanded version of this article appears in the Love & Death issue of The Mockingbird Magazine.

COMMENTS

16 responses to “When You Marry the Wrong Person”

Leave a Reply

Top notch stuff, Dave, and so true. Reminds me of what Stanley Hauerwas calls Hauwerwas’ Maxim: You always marry the wrong person.

this is the kind of post that i didnt want to end. very nice dz. also lol at : “we arent identical obviously/thankfully”

Best piece on marriage I’ve read!

One paragraph confirmed what Eddie Murphy said in the 1987 stand up film, ‘Raw’….”there’s no perfect people…you just gotta find somebody who’s as f***ed up as you are!”

In my case, my wife found someone more effed!

🙂

Btw, I also appreciated the insight that optimism doesn’t bring the hope it promises – it kills it. So true…thank God for His divinely appointed, yet sobering pessimism that constantly brings us back to the gospel so we can breathe, live, and enjoy life! Theres something to be said for the fact that Song of Songs follows Ecclesiastes!

Haha, there are a lot of wrong marriages in GoT. 😉 Thanks for this excellent post, David. We LOVED Alain’s NYT article as well.

Cheers,

Nick

“…not even death can do us part.” Beautiful. Thanks for this!

Hauerwas fwiw often has added to the maxim as texted above, “…even the second time”.

Love this. Thank you!

“This groom is under no illusions about what he’s getting/gotten himself into. Those have been stripped away. … He knows that “the wrong people” are all there are, that none of us are very good at loving or being loved. Yet he refuses to spare himself the heartache, thank God. …he is the opposite end of the cultural spectrum incarnate, and not even death can do us part.” Oh thank God!

This is an excellent post, honestly probably the best one on marriage I’ve ever read. Very helpful. Thank you for writing it David.

A long time ago, Theodore Reich wrote, “Show me who you love and I will show you who you want to be.”

Reminds of a recently read article: “The Biggest cause of marriage problems or failure: False Expectations”. Good article.