Spoiler Alert for those who have not yet seen this past week’s episode of Game of Thrones (Season 6, Episode 5).

A drunk King Robert gallivants across a wooden stage, two conspicuous stagehands tracking his movements with a poorly-painted backdrop of woods behind him, setting the scene. Bawdiness, drinking jokes, and other low-comedy staples ensue, until dunderhead Ned Stark, idiot/villein Northern companion of the lecherous Robert, tries to grab the Throne for himself, until Joffrey, Cersei, and Littlefinger intervene to keep the pretender from taking power.

Last night’s Game of Thrones episode was brilliant in lots of ways, but from a critical standpoint, at least, this was the most interesting. The show itself traffics in violence, nudity, sex jokes, and caricatures, so in some ways the play is a parody, or even a sort of reduction to its basics, of the show. In the play, after the boar guts King Robert, his entrails spill out, strips of stuffed crimson cloth, the equivalent of special effects without modern technology. And the show’s use of special effects, perhaps more pronounced than ever before in last night’s scenes of the Children and the Walkers, is more convincing, but still an illusion. So what makes the show different from the play? Just budget and technology, or something more fundamental?

One advantage of the show might be the way it forces us to reckon with the problems and costs of storytelling. During the play, the camera cuts back and forth from the stage to Arya Stark’s face as she watches, trying to fight down her visceral reactions to her father’s brutally misleading characterization in the play. She’s trying to be “no one,” the Faceless Men’s ideal of an empty vessel for the Many-Faced God’s will, without any personal predilections or priorities. “A girl has no desires,” as Arya tells her mentor. But while everyone else in the play’s audience laughs and jeers and just unreflectively comes along for the ride, she alone suffers, because she alone knows that this story has a cost; it promotes a lie, and it does violence to her, and to her father’s memory, in the process.

A challenge always present in the show for the last season and a half or so, but never quite brought to the fore, is that of how to tell a redemptive story of history. Last season the showrunners faced harsh criticism that all the brutality they made us watch with Ramsay Snow and Sansa would not have a payoff. The audience suffered, Sansa suffered unspeakably, and there was no payoff; critics kept demanding that the violence not be gratuitous, which means that the violence not be there for its own sake. In other words, they were all ready for Sansa to decide that enough’s enough, and she’s taking full control of her destiny. According to lots of critics, in other words, the only way to justify those scenes’ inclusion in the show was if Sansa came out the other side at a further point in her character ‘arc’, i.e., came out the other side a more forceful, influential person.

She did, we learned last night, in a confrontation with Littlefinger, but as she says, those wounds don’t automatically go away just because you’ve progressed further along your ‘character arc.’ And those critics’ demands that her suffering have a redemptive purpose are in some ways legitimate ones, but they risk looking at suffering as a means to an end, of connecting suffering with some justificatory purpose. It’s hard though, and it’s a brutal line to take in some ways, since so many who suffer never get to look Littlefinger in the eye and tell him they already have an army, thank you very much, and many who suffer end up having their lives irretrievably destroyed by it. Benioff and Weiss may have gone a little too far in the gratuity direction with Ramsay the prior season, but such gratuity is a fact of life. There is not always a redemptive purpose to suffering, and one can imagine a sufferer watching Theon or Sansa last night, as their arcs ‘pay off’, and wonder why that empowerment hasn’t yet happened to them.

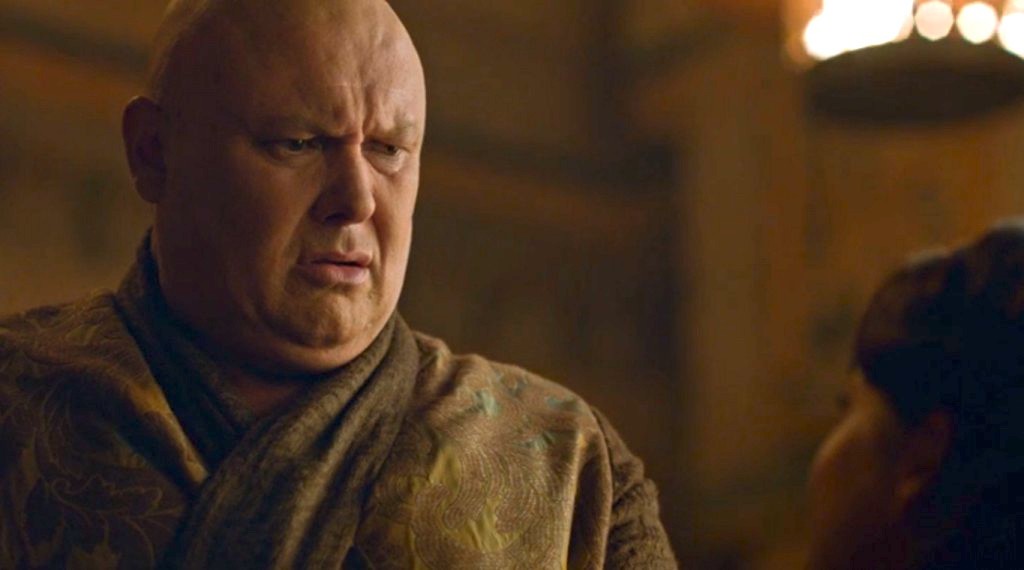

In fact, this view takes on a moralistic tone, and it’s no coincidence that when Benioff and Weiss want to address this means-ends way of thinking head-on, they put it in the mouth of a fundamentalist religious leader. The Red Priestess in Mereen, Kinvara, tells Tyrion and Varys that Daenerys is the one who was promised, a messiah to deliver the world in the coming apocalyptic battle with the forces of evil, almost certainly the White Walkers. Tyrion’s a skeptic, but he’s happy to have religion helping him keep a firm hold on turbulent Mereen; Varys, however, is something more than a skeptic. When he was a boy, Varys’s ‘man parts’ were cut off by a sorcerer who threw them into a fire as a catalyst for a spell, and he has hated magic – and seemingly, religion too – ever since. He was a means to something presumably greater, a slave-boy sacrificed to create a transcendent magical spectacle. So he cannot stand the confidence of people like Kinvara, ready to make any sacrifice for her personal convictions about the world. When he challenges her, pointing out that her colleague Melisandre’s convictions about Azor Ahai were wrong, she narrates his story for him. If he hadn’t suffered the immense pain and degradation of being castrated, he never would have risen to his position as one of the most influential people in the world.

On its face, the story is a true one; the critics were right about Sansa to the extent that suffering often does end up leading to greater strength and character and resolve. It is also, however, a brutal story, inasmuch as Varys never chose to be a pawn in the sorcerer’s scheme, in the great war between light and darkness, or even in Martin’s narrative. So ultimately the question becomes one of who decides which stories are redemptive and which ones are not. The sorcerer discerned a higher purpose in Varys’s sacrifice, but he was wrong. Kinvara discerns a higher purpose in Varys’s suffering, and she may or may not be wrong. But that question, of whether the ends are sufficiently important to justify the hard road to them – i.e., the question of whether suffering may be redemptive – risks insensitivity to the degree it still operates in a means-ends framework. On the one hand, if Varys’s talents allow Daenerys to save the whole world from a zombie apocalypse, then of course any sacrifice is worth it. On the other hand, nothing can make up for, or justify, what Varys went through. Hence his aversion to those religious people who are always claiming to see the bigger design, an aversion to those who claim to make any sort of narrative sense out of suffering.

Ultimately the only way to break the brutal logic of ends and means – a logic too often fortified by simplistic theodicies like that of Kinvara – is self-sacrifice. The only time we can vindicate suffering in terms of a higher purpose is when the sufferer, rather than storytellers, prophets, or even a god, makes the choice and decides the higher end is worth it.

These threads converge beautifully in the closing sequence of Bran, Meera, and Hodor in the cave as the Walkers attack. With precious little time before the Night’s King arrives with his army, Bloodraven (Bran’s mentor) chooses to show him not the secrets of Jon Snow’s parentage, nor the building of the Wall, nor any other scene which would make him more powerful in the battle to come. Instead, Bloodraven shows him the onset of a permanent disability in a stableboy at Winterfell named Hodor. Because it is not ultimately the epic things, the grand design, the big stories we tell, which matter, but rather the little lived experiences of daily life, which form, at an emotional level, a deep instinct for the costs of our own character ‘arc’, the collateral damage of our linear paths towards progress. So to prepare Bran for wielding his new power, Bloodraven’s final lesson to him must be not even a lesson, but a lived experience of the cost of his power, his arc as an eventual hero.

If we could go back in time and stand in these little moments, we might see that these unrecorded sacrifices from others condition who we are and where we are. It might be something as big as a parent forgoing a major career opportunity because you liked your fourth-grade friend group and were terrified of moving to a new city, or something as small as an older sibling staying in and talking you through an insignificant emotional crisis – a breakup with an eighth-grade girlfriend, say – when they had much better things to be doing that night. I suspect that witnessing any one of those little sacrifices, even, would be deeply touching and tremendously humbling.

The grand stories too quickly lose touch with this critical dimension of life – this messy web of interpersonal sacrifice, selfishness, dependence, love – which we tend to overlook already. How much more affecting would be the knowledge, which dawns gradually on past-Bran’s face, horrified and transfixed at the sight of Hodor’s seizures, that someone’s entire life existed only to give you a chance at escaping from a cave.

Perhaps Bran’s arc, and his role in the wars to come, will justify that sacrifice from a detached, critical, storytelling point-of-view. Regardless of what we as critics think, though, that part of storytellers and their critics who are human beings, also, may not rationally believe but at least feels that no amount of payoff can justify or even compensate for the destruction of a single life. And that feeling of the fundamental incommensurability of suffering and payoff rings devastatingly true, which means that there is some fundamental level of gratuity in everything; in the little and big sacrifices of which neither Bran, nor you or I, are remotely worthy, whether we save the world from zombie-apocalypse or not.

It’s certainly plausible, and maybe even likely, that Hodor’s an unwilling tool for grandiose ends and arcs about which he knows nothing. We never see Bran warg into him directly, and Meera’s exhortation becomes his mantra for his entire life; so while he holds the door as zombie-arms claw at his face from the other side, I can’t help but think that in the actor’s facial expressions there is something which almost suggests free choice. But it’s ultimately a grey area on whether Hodor was completely used or chose, in some instant, to make that sacrifice, and this is fitting.

Real life is messy, and the sacrifices which others make for us, even the willing ones, create an incommensurable debt; for Bran, because of the grey area, that incommensurability could ripen into immense gratitude or immense guilt, and maybe the line between the two isn’t as clear as it sometimes seems. But the project of trying to explain those sacrifices in terms of means to a justified end, or a painful step on an ultimately redemptive character arc, risks in fact being a way to render logical what is ultimately incommensurable, and thus to gain some sort of narrative mastery over the gratuitous events of life. So even while driving the grand story forward, Martin and the showrunners pause to give us a close, heartrending look at the gaps in the stories we tell as well as their costs, reminding us in the process that even in high fantasy, the unwritten sacrifices of history are the hidden foundations on which many good things are built.

COMMENTS

6 responses to “The Door and the Stories We Tell: Reviewing Game of Thrones”

Leave a Reply

http://uploadpie.com/znE3X

Well written. And I don’t even watch GOT. I sit in the kitchen while my wife and son watch and discuss, and then the next day I read the reviews. I left off over the gratuity of so much of the narrative. Like I did with House of Cards and the Walking Dead. As a pastor and priest for more than 30 years I have seen the marks left in so many when suffering feels like it cannot be redeemed. And yet perhaps I forget the arc. I am now reminded of those Hobbits. Those little people trying to be forgotten in their Shire, who nonetheless make their seemingly small sacrifices, unnoticed, “small,” and yet a new age is ushered in. Nice. Thanks.