At 17, I read The Bell Jar. After grimacing through the suicide attempts, the shock therapy sessions, the nervous breakdowns, and the general darkness, I closed the book, appreciated the work, and then thought, “Damn. This woman was crazy.”

At 17, I read The Bell Jar. After grimacing through the suicide attempts, the shock therapy sessions, the nervous breakdowns, and the general darkness, I closed the book, appreciated the work, and then thought, “Damn. This woman was crazy.”

At 21, I thought my life had become The Bell Jar. I felt the same suffocating dread Plath expressed in her characters’ fears of “settling.” I wallowed in my failures, was crippled by indecision, felt misunderstood, tired, and nervous. About everything. Plath was my female masthead, unapologetically vocalizing every one of my rite-of-passage fears with poetic authenticity.

Then, just last week, my English major survey professor concluded our class on Sylvia Plath’s Ariel by saying, “Now, most Plath readers think they understand where she’s coming from. They think they’ve been there themselves. But they haven’t. Don’t try to understand. You won’t. You just won’t.”

Initially, I was furious. Me, not understand? Me, unable to grasp the deep-seated brooding, the anger, the depression, the anxiety? Me, a 22-year old soon-to-be graduate with no direction and no job, inhibited from harnessing Plath’s hardly-subtle neuroses? Me, a “millennial,” a member of perhaps one of the most angst-laden generations to grace the earth yet? How dare he suggest I couldn’t understand!

Of course, most of us can’t pretend to have really reached the precipice of understanding the yearning for finite death. True, I had never been suicidal myself, but I’d certainly made room in my mind for the dark, artistic meditations represented in “Plathian” lore. As cases of depression became more and more prevalent in friends and family members (and even fictitious characters), and given the visceral reality of the recent statistics published by the National Institute for Health, I stretched my mind to both contend against and play host to the shadowy tempest that (I supposed) must plague the minds of those suffering. Existential contemplation provided a sense of profundity, and I careened toward what I thought was a spot-on connection with and comprehension of Plath’s work.

However, I also noticed a twisted satisfaction emerge from the pain. Whenever I began to feel sad, or perturbed or troubled, I felt closer to those whom I knew to be in anguish themselves. I thought that I was deepened, strengthened, and toughened by this despair. I cherished the kinship I felt with Plath’s agitated mind, because, in a sense, ‘feeling anxious’ in and of itself allowed me to also recognize my own ability to empathize.

However, I also noticed a twisted satisfaction emerge from the pain. Whenever I began to feel sad, or perturbed or troubled, I felt closer to those whom I knew to be in anguish themselves. I thought that I was deepened, strengthened, and toughened by this despair. I cherished the kinship I felt with Plath’s agitated mind, because, in a sense, ‘feeling anxious’ in and of itself allowed me to also recognize my own ability to empathize.

In a poem titled “Nick and the Candlestick,” Plath writes, “You are the one/ Solid the spaces lean on, envious.” In another called “The Secret,” it reads “A secret! A secret!/How superior.” These, in effect, described how I’d come to view—and embrace—my own grappling with mental health. The despair was, by nature, troubling, but by feeling it on my own and then lending an “empathetic” ear to others encumbered by the same heaviness, I felt solid. I had a secret, and though it was dark, it was gratifying. Angst became an indulgence; this secret lent superiority, and having the ability to understand others in the same situation was worthy of envy. I paired anxiety with pride.

This paradox is paralyzing; it simply cannot produce a forward-moving trajectory. With bizarre rationale, we often believe that sadness gives us momentum. We may be reeling, sure, but as we see ourselves hurtling towards catastrophe (of an unidentifiable nature), the ultimate combustion also presents itself as an opportunity. If we are broken, well, we could recollect the shards and package them as something within our own control. In being depressed, we possess an element of ourselves that cannot be explained nor owned by anyone else. However, in my case, by “allowing myself” to “really feel” the gloom, I had, in truth, stopped myself from moving.

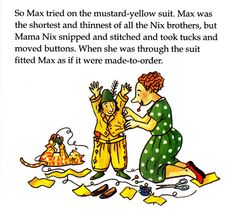

Three nights ago, I discovered (rather embarrassedly as a self-proclaimed lover of Plath) that she had written two children’s books. One is called, “The It-Doesn’t-Matter Suit,” a sing-songy portrayal of a young boy named Max who develops true self-confidence when a bright yellow wool suit arrives by mail that fits him perfectly. The other is called “Mrs. Cherry’s Kitchen,” and though less “critically acclaimed,” the story humanizes Plath in a manner unparalleled in her otherwise neurotic turns of phrase. In the book, Mrs. Cherry’s kitchen appliances all decide that they want to disregard their functions and pursue their “dream jobs.” They consult the kitchen pixies, “Salt and Pepper,” who relegate each appliance in turn to a different task:

Three nights ago, I discovered (rather embarrassedly as a self-proclaimed lover of Plath) that she had written two children’s books. One is called, “The It-Doesn’t-Matter Suit,” a sing-songy portrayal of a young boy named Max who develops true self-confidence when a bright yellow wool suit arrives by mail that fits him perfectly. The other is called “Mrs. Cherry’s Kitchen,” and though less “critically acclaimed,” the story humanizes Plath in a manner unparalleled in her otherwise neurotic turns of phrase. In the book, Mrs. Cherry’s kitchen appliances all decide that they want to disregard their functions and pursue their “dream jobs.” They consult the kitchen pixies, “Salt and Pepper,” who relegate each appliance in turn to a different task:

And Whizz! Whirr! Bang! Clang! The shirts go into the oven, unbaked plum tarts go into the icebox, the coffee percolator swallows ice cream, the iron tries making waffles. Unsurprisingly, they all fail miserably.

In a sense, a personal affinity for Plath’s literature—and the reflection of self we see in her lines—is much like the coffee percolator swallowing ice cream. Or the iron trying to make waffles. We attempt to process notions of angst as “artistic” and “perceptive,” and we can see our anxieties as something within our jurisdiction. We turn our vulnerabilities into strengths rooted in misinterpretation and a superficial regard for secrecy–we self-justify to maintain pride with emotions that are, when regarded viscerally, overwhelming. Interestingly enough, “The Secret” ends as follows:

Dwarf baby,

The knife in your back.

‘I feel weak.’

The secret is out.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “Misunderstanding, Misunderstood: The Sylvia Plath Who Wrote For Children”

Leave a Reply

A wonderful read, Lizzie. I’ve always been intrigued by Sylvia Plath. You offered some great insight!

Of course, Plath eventually ended her life over this angst, but you’re right. We millenials are stupid. It would be so funny if we weren’t so serious all the time about authenticity and feelings. I can sympathize with your feelings coming out of college, having gone through them myself. And yet, they are but shadows on the wall of our delusional perspective on life. Middle Class sensibilities are like a vaccine for seeing reality. And I say this as a 20-something who is many times blinded by the same pathological angst-arrogance vis. depression and confusion.

Also: I also understand the empathy through “understanding” others going through the same. But as I’ve realized (maybe we’ve had different experiences), the times where I felt “superior” were when I wasn’t really listening or truly being present. Instead, I was more fixated with myself, thinking about how I am able to be there for this or that person, while simultaneously not being there. Once I started to listen and be more present, the whole thing crashes and it’s an exercise in drinking emotional poison, like sucking snake venom out of a bite. But, as per Christ’s promise in Mark 16, we can drink poison and live.