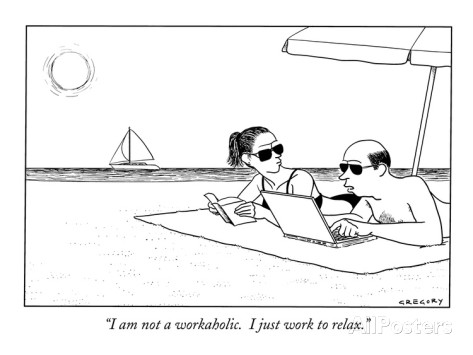

“Why do we work so hard?” asks one of the lead articles in 1843, the new bimonthly journal from the people responsible for The Economist. The tagline only upped the ante, bait-wise, promising to trace how “our jobs have become prisons from which we don’t want to escape.” Writer Ryan Avent looks under quite a few stones in search of his answer, some flattering and some less so.

He opens with the observation that we work more than ever today, not just because our employers or the economy demand it of us, but because work has become that much more enjoyable. In contrast to previous generations, at least. But Avent only half settles for that explanation, raising the question of Stockholm Syndrome pretty early on. After outlining the basic mechanics of globalization-driven escalation, he surfaces the false promise/premise from which so much contemporary worklife flows:

The dollars and hours pile up as we aim for a good life that always stays just out of reach. In moments of exhaustion we imagine simpler lives in smaller towns with more hours free for family and hobbies and ourselves. Perhaps we just live in a nightmarish arms race: if we were all to disarm, collectively, then we could all live a calmer, happier, more equal life.

But that is not quite how it is. The problem is not that overworked professionals are all miserable. The problem is that they are not…

That’s the rub, eh? The real, and more uncomfortable, question when it comes to workaholism and “the cult of productivity” is not so much why we work such insane hours, but why we have come to prefer it. The issue is not cut and dry; he wisely points out that part of the attraction to overwork is the passion and interest that more and more people in the workforce are able to bring to their careers. In white collar fields at least:

Workers in cognitively demanding fields, thinking their way through tricky challenges, have always done so at odd hours. Academics in the midst of important research, or admen cooking up a new creative campaign, have always turned over the big questions in their heads while showering in the morning or gardening on a weekend afternoon. If more people find their brains constantly and profitably engaged, so much the better…

Fair enough. It’s nice to enjoy what you do from 9-5, a privilege not to be taken for granted. After all, the idea (to say nothing of the injunction!) that we would find our work personally fulfilling is a fairly radical one, historically speaking. But here’s where Avent goes beyond most commentators:

There are downsides to this life. It does not allow us much time with newborn children or family members who are ill; or to develop hobbies, side-interests or the pleasures of particular, leisurely rituals – or anything, indeed, that is not intimately connected with professional success. But the inadmissible truth is that the eclipsing of life’s other complications is part of the reward.

It is a cognitive and emotional relief to immerse oneself in something all-consuming while other difficulties float by. The complexities of intellectual puzzles are nothing to those of emotional ones. Work is a wonderful refuge…

We love the office, in other words, because it allows us to feel productive and worthy while distracting us from deeper, less manageable realities. To put it in Law/Gospel terminology, if work has traditionally been a means of appeasing judgment, today it is that and a way of fleeing from it, simultaneously. A distraction from conscience, or loneliness, or grief, or simply vulnerability–a way of imposing order on the chaos of relating to another person or even oneself, to say nothing of God. Like the addicts we are, captivity to the illusion of control is not merely our dereliction but our predilection.

He highlights the self-justification aspect further when he discusses a friend’s failed attempt to downshift their pace by moving from DC to–get this–Charlottesville:

Stepping off the treadmill does not just mean accepting a different vision of one’s prospects with a different salary trajectory. It means upending one’s life entirely: changing locations, tumbling out of the community, losing one’s identity. That is a difficult thing to survive. One must have an extremely strong, secure sense of self to negotiate it….

Well, shucks. If only that were true! But as we all know, ego-centric enslavement to the law isn’t limited to big cities. Perhaps certain (type-A) expressions are more concentrated there, but rest assured, here in “the happiest city on Earth” we are more than covered in the identity treadmill department.

I admire the honesty with which he confesses his own conflicted thoughts about work-life balance:

I want hours of quiet to write in, not days and weeks. I would miss, desperately, being in an office and arguing about ideas. More than that, I could anticipate with perfect clarity how the rhythm of life would slow as we left the city, how the external pressure to keep moving would diminish. I didn’t want more time to myself; I wanted to feel pushed to be better and achieve more. It wasn’t the stress of being on the fast track that caused my chest to tighten and my heart rate to rise, but the thought of being left behind by those still on it…

There you have it: life conceived as a competition. Which he clearly doesn’t see in as baneful a light as we might. Perhaps because there’s a security and even comfort in a head-down mentality, no matter how illusory the destination or finish line may be. One foot in front of the other crowds out uncertainties.

It is telling that the rigor of the race itself is not what inspires panic in Avent, but the fear of failure–of coming up short. What we might call condemnation. It’s a little ironic, since his work seems to involve figuring out why he’s running in the first place. Oh well. Awareness never saved anyone.

My favorite paragraphs come toward the end. The first being when he describes how the whole enterprise operates not only on an individual level, but a social one. We surround ourselves with those whose self-salvation projects look most like our own:

The society of people like us reinforces our belief in what we do. Working effectively at a good job builds up our identity and esteem in the eyes of others. We cheer each other on, we share in (and quietly regret) the successes of our friends, we lose touch with people beyond our network. Spending our leisure time with other professional strivers buttresses the notion that hard work is part of the good life and that the sacrifices it entails are those that a decent person makes. This is what a class with a strong sense of identity does: it effortlessly recasts the group’s distinguishing vices as virtues…

Ooof. Again, these principles function universally, not just for overachieving workaholics. Substitute “strivers” for “activists” or “artists” or “ministers”, and you have pretty much the same thing.

He ends by painting a picture of the closed circle of the law in vivid, almost cult-like colors. A paraphrasing of Romans 8:20 if not the full “curse” of Galatians:

To build my career is to make myself indispensable, demonstrating indispensability means burying myself in the work, and the upshot of successfully demonstrating my indispensability is the need to continue working tirelessly. Not only can I not do all that elsewhere; outside London, the obvious brilliance of a commitment to this course of action is underappreciated. It looks pointless – daft, even.

And I begin to understand the nature of the trouble I’m having communicating to my parents precisely why what I’m doing appeals to me. They are asking about a job. I am thinking about identity, community, purpose – the things that provide meaning and motivation. I am talking about my life.

Suffice it to say, works righteousness ain’t just a river in Egypt. Fortunately, neither is the God “whose property is always to have mercy”. I suppose I could go on, but there’s a podcast to record, a sermon to write, a weekender to curate, a magazine to mail and a conference to run. Giddy up!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SHAaP4SLmxU

COMMENTS

6 responses to “Why Do We Work So Hard?”

Leave a Reply

Needed this. Thanks Dave.

Good stuff, Dave (as always)!

“There you have it: life conceived as a competition. Which he clearly doesn’t see in as baneful a light as we might. Perhaps because there’s a security and even comfort in a head-down mentality, no matter how illusory the destination or finish line may be. One foot in front of the other crowds out uncertainties.” If you keep your head down in hockey, you are setting yourself up for a terrible disruption when someone sets you up for a head banging check. It would seem that this will be what comes when life let’s you have it if you use your work to hide. This sounds a bit like Ernest Becker’s The Denial of Death and our immortality projects. It was one of the books that Gerhard Forde used to make us read upon returning from internship to point out the dangers of self-justification. Thanks for the blog, I will go home now.