This review comes from Gilbert Colon.

Mikhail Bulgakov, grandson of two Russian Orthodox priests, is experiencing a minor resurgence. The Soviet-era author’s short story collection, A Young Doctor’s Notebook, finished a two-season run in 2014 as an Ovation cable series starring Mad Men’s Jon Hamm and Harry Potter’s Daniel Radcliffe. Russian television turned his novel The Master and Margarita, about Satan coming to Stalin’s Moscow, into a 2005 miniseries. And finally this year saw, thanks to Manhattan’s The Storm Theatre (at St. Mary’s Church, 440 Grand Street), the American premiere of the Bulgakov bioplay Collaborators, first staged at London’s National Theatre in 2011 by Nicholas Hytner (who filmed The Crucible in 1996).

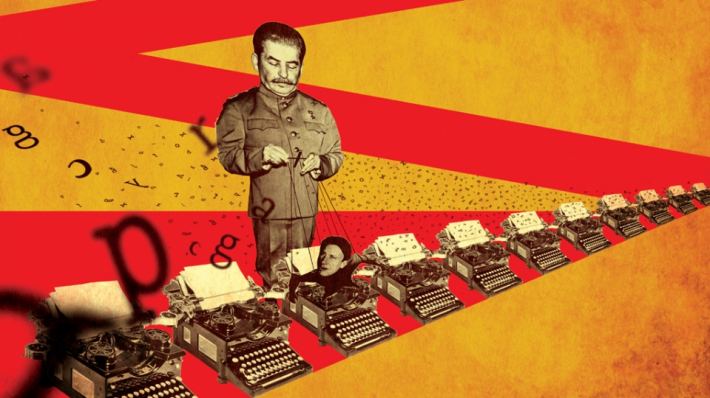

Collaborators playwright John Hodge (screenwriter of Danny Boyle films like Trainspotting) imagines a Moscow Art Theatre collaboration between the Russian writer (actor Brian J. Carter) and the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin (Ross DeGraw). Stalin, impressed by Bulgakov’s The White Guard, strong-arms Bulgakov into writing for him, as Kathy Bates does to her favorite author in Misery or, more aptly, like when China’s first emperor Ying Zheng abducted musician Gao Jianli to compose a national anthem (depicted in the 1996 film The Emperor’s Shadow). This same emperor is revered as a Mao-like “Hero of the Revolution” in the Red China-sanctioned martial arts masterpiece Hero from filmmaker Zhang Yimou, another artist possessing an uneasy give-and-take history with apparatchiks. (Zhang even staged Tan Dun’s opera The First Emperor about Gao’s struggles.)

These examples are the tip of the iceberg in demonstrating what amounts to a niche subgenre (just as Hodge’s play jokes about an esoteric Soviet “genre in itself” glorifying “counter-revolutionaries who see the light through the purifying effects of digging a canal”). Films like Testimony (1988), casting Ben Kingsley as composer Dmitri Shostakovich, and Inner Circle (1991), starring Tom Hulce, portray Stalin’s relationship with music and movies, as Collaborators depicts his with theater. These complex meditations on art and politics involve a complicated personality – a tyrant – who complicates issues of individual creativity, and this phenomenon is not restricted to Stalin. Along with Emperor Ying Zheng, there is North Korean communist dictator Kim Jong-Il kidnapping director Shin Sang-ok and actress Choi Eun-hee to make movies for him, a strange but true story covered in the upcoming documentary The Lovers and the Despot.

For Collaborators, Hodge makes a conscious decision to use colloquial speech, a choice yielding interesting results in this production. Big Joe Stalin sounds more John Goodman than Georgian, underscoring a Barton Fink quality to this play. (Writer’s block is overcome when the scribe meets his muse, a psychopathic mass murderer.) Yet Bulgakov, unlike Fink and the card-carrying communist Clifford Odets upon which he was based, was no socialist, despite his compromises. Interestingly Barton Fink’s filmmakers, the Coen Brothers, plan to someday film a sequel set in the years after their Odets stand-in finks on Hollywood to HUAC. Art, politics, and (as shall be seen) careerism collide.

Collaborators’ NKVD secret police begin as menacing before becoming as madcap as Kurt Vonnegut’s neo-Nazis in Mother Night. Against all odds, the playwright pulls off this inadvisable comic touch. The chief NKVD officer (Robin Haynes) admits he only intended for Bulgakov’s wife Yelena (Erin Biernard) the kind of mock execution that turned Dostoyevsky towards God, not the real thing. Deep down all he wants to be is an artiste, finally fulfilling this dream as director of Bulgakov’s Young Joseph (another collaboration). But even this loyal and brutal NKVD officer sneaks subversion into the work when Stalin unleashes his full “avalanche of terror.”

Behind the NKVD’s back, Bulgakov has Stalin himself as ghostwriter, the pair collaborating on the agitprop play Young Joseph. Collaboration, however, has more than one meaning. In a reversal of roles, Stalin types while Bulgakov handles matters of state. Bulgakov reviewing Stalin’s enemies list with the dictator play like Marlon Brando in The Godfather advising Al Pacino that “whoever comes to you with this Barzini meeting, he’s the traitor.”

If this sounds absurdist or farcical, the real Bulgakov did write farce – or “tragifarce,” as author and theater professor Julia Listengarten terms it, meaning “an extreme form of tragicomedy.” Highlighting this are Collaborators’ two plays-within-a-play – one Bulgakov’s biographical play about French satirist Molière, the other Young Joseph. The ironies pile up as Stalin, the failed Russian Orthodox seminarian, writes a scene for Bulgakov outrageously likening his early self to Christ climbing Calvary.

In the end, Hodge’s burlesque is serious business. As the number of liquidated “traitors” escalates to Holocaust proportions, the consequences of self-deluded collaboration dawn late on Bulgakov as they do to Alec Guinness’ The Bridge on the River Kwai character – “What have I done?” Has Bulgakov become Hendrik Höfgen in Mephisto (the Klaus Mann novel or 1981 film), the career-minded actor who strikes a Faustian bargain with the Third Reich to become its premier performer? Regardless of remorse, the uncomfortable fact is this Bulgakov – in the last days of kidney failure – agrees to Young Joseph so his Molière play can go on. Collaborators, like Young Joseph, is a fantastical imagining, but a fact-based one – while Bulgakov never signed death warrants for Stalin, historically he did script one final play called Batum, about Stalin the young revolutionary, which Hodge admits to “renaming…and subjecting…to parody.” Indeed Stalin himself commissioned Batum, decreeing it “very good,” but ultimately “not to be staged.”

The Storm Theatre program marvels:

It is impossible to research the history of the Soviet Union and not be shocked by the number of Western artists and intellectuals who supported [a] truly…‘Evil Empire’ … Tyranny cannot exist without the collaboration of artists and intellectuals who promote its agenda…

Bulwarking this commentary is an Alexander Solzhenitsyn quote:

The communist regime in the East could stand and grow due to the enthusiastic support from an enormous number of Western intellectuals who felt a kinship and refused to see communism’s crimes.

This contextualization begs whether Collaborators is preaching to the choir, or will it win hearts and minds sold on Warren Beatty’s Reds myth?

Or sold on the recent Trumbo (2015) as the last word on the subject. The Coens’ latest, Hail, Caesar!, astonishingly admits to communist flirtation and infiltration in 1950s Hollywood. Its “useful idiot” Baird Whitlock (George Clooney) is an actor so vacuous and weak-minded who, after being kidnapped by communist brainwashers, instantly succumbs to Stockholm Syndrome and starts spouting Marxist theory. It is an infuriating reminder how easily hijacked intellects of that era were, like today’s. So-called intellectuals who reflexively take Woody Allen’s The Front as gospel busily see Nazis and Fascists under every bed, never coming to terms with the lurking totalitarian sympathies of many of their blacklisted idols. Their romanticized ancestors and descendants include fellow travelers H. G. Wells, Jane Fonda, and Michael Moore, true believers at best delusional and at worst willfully blind when they saw workers’ paradises where there were only Gulag Archipelagos.

The sad irony is that this crowd may never see themselves in Bulgakov, a dissident exercising free speech, but the film community still occasionally offers up a Doctor Zhivago (the 2002 Masterpiece Theatre remake), The Lost City (2005), or The Lives of Others (2006). On the other hand, the 2011 musical Doctor Zhivago failed on Broadway, and tellingly it has been a while since anyone has filmed George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four – the last adaptation was in 1984, and roughly three decades later bona fide socialism emerges in an American presidential election.

As it typical of New York theater, nearly everyone in Collaborators’ talented cast has Law & Order credentials, and its production staff maximizes its relocated space by filling out the Soviet collective one-bedroom apartment set with plenty of period accessories. The Storm Theatre’s ambitious artistic director, Peter Dobbins, has challenged the evils of communism before on the Storm stage. In 2014 he mounted Our God’s Brother, penned by the future St. John Paul the Great, one third of the troika credited with collapsing the Soviet system. He produced it once before, along with that pope’s The Jeweler’s Shop, Job, and Jeremiah, as part of his Karol Wojtyła Festival. In addition to staging conventional choices like Shakespeare, Dobbins presented the Paul Claudel Project (The Tidings Brought to Mary, The Satin Slipper, and Noon Divide), a trio of that playwright’s rarely-produced works (all Christian-themed without being religious tracts).

Collaborators’ five-week run ended on February 13th, so while Broadway remains stuck in the rut of making musicals out of movies like Kinky Boots and Leap of Faith, it is always worth the wait to see what is brewing next at The Storm Theatre.

Gilbert Colon has appeared in Cinema Retro, Filmfax, Crime Factory, Crimespree Magazine, bare•bones, and the St. Martin’s Press newsletter Tor.com. Besides being a regular reviewer at The Catholic Response, he has contributed to RELEVANT Magazine, Sentieri del cinema, The Lewis Review, and MercatorNet. Comments are welcome at gcolon777@gmail.com.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply