Sermon on the Rocks, the new offering from Josh Ritter, opens with the slow-burning, apocalyptic “Birds of the Meadow,” a song aiming for prophecy that repeats the refrain, “Fire is coming, fire is coming.” These are the words of those who stand on street corners bellowing through megaphones: hellfire and damnation, intoned by Ritter in a deep, foreboding tone that matches the lyrics. For those of us who have grown up surrounded by American Christianity, these words sound all too familiar, resounding with notions of an angry God, just biding his time before coming to purge the world with fire. If you’d never listened to Josh Ritter before, “Birds of the Meadow” might suggest an album consumed with judgment and fear…but, then again, the record is called Sermon on the Rocks, and it lives up to its title far more than its opening track. Starting with a dark vision of the end of the world, Ritter takes listeners on a journey through religious impulses, natural beauty, and human relationships, challenging doomsday narratives and ultimately arriving at a more optimistic, loving vision of the world.

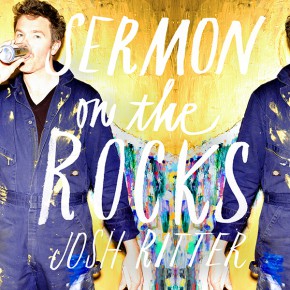

Calligraphy on the cover by our good friend Stephanie Fishwick–also responsible for the design of this site (and a bunch of our books!).

Musically, Sermon on the Rocks does not stray too far from Ritter’s country-inflected singer-songwriter style, although it does sparkle with an energy that his last album, Beast on the Tracks, was, at times, missing. On Sermon on the Rocks, every song has a distinct personality, from the upbeat, tongue-in-cheek honkytonk of “Getting Ready to Get Down” to the layered, soaring atmosphere of “Homecoming.” Moreover, the album’s pacing is spot-on, alternating between the fast and the slow, not just from song to song, but sometimes within individual songs like on “Young Moses.” In doing so, Ritter avoids the tendency of singer-songwriter albums to get bogged down in the same tempo, instead crafting an album that highlights his lyrics by pairing them with the appropriately inflected music. And that’s good, because he’s got plenty to say.

Religious themes and issues abound on Sermon on the Rocks. “Getting Ready to Get Down” tells the story of a girl, whose parents sent her off to Bible school in hopes of curbing her baser instincts, but, as the song’s title suggests, that plan doesn’t quite work. Rather than focus on the girl, Ritter turns his criticism upon those in authority, suggesting that perhaps their legalism is more to blame than her desires. He also points out how certain strains of American Christianity tend to elevate certain behavioral rules to the level of essential belief: “All the men of the country club, the Ladies of ‘Xiliary/ Talk about love like it’s apple pie and liberty/ To really be a saint, you gotta really be a virgin/ Dry as a page of the King James version.”

On “Young Moses,” Ritter refuses the “house of gold” promised in the first verse to roam among the American countryside, content to find his spirituality among nature and others rather than in “traditional” images of heaven. While Ritter appeals to several different religious/spiritual traditions in “Young Moses,” his larger point rings true: why look for God in heaven when you can see him reflected in the world?

This naturalistic spirituality occupies several of the later songs on Sermon on the Rocks, pointing to the world as beautiful and redemptive in its own right. On “Cumberland,” an upbeat ode to the country, Ritter encourages us to get back in touch with nature in decidedly spiritual terms: “Take a little drive, take a little trip to heaven/ And wonder if it’s paradise or Cumberland.” Ruminating on a troubled relationship, “A Big Enough Sky” suggests that the solution may lie in a simple remembrance of humanity’s place in this world. Ritter sings, “I believe a lot of things honey/ When the sky is big enough,” connecting his ability to believe to the landscape surrounding him. Indeed, many of us seem to have profound spiritual experiences when we remove themselves from our frantic lives and head out into the country for a few days. But, what about when we come back from the mountaintops and the wide open spaces? Does Ritter have anything to say about that?

LONDON, UNITED KINGDOM – APRIL 18: Josh Ritter performs on stage at Scala on April 18, 2011 in London, United Kingdom. (Photo by Kate Booker/Redferns)

While the exuberance of songs like “Cumberland” and “Young Moses” stands out, Ritter does not shy away from pain on Sermon on the Rocks, highlighting a human darkness that seems to permeate everything, even the goodness of the natural world. Throughout the album, the darkness battles the light, musically and lyrically (for example, “Henrietta, Indiana” immediately follows “Young Moses,” turning joy to sorrow) with one important exception—the end of the album. After comparing love to fire on “Lighthouse Fire,” Ritter ends Sermon on the Rocks with “My Man on a Horse (Is Here),” a song that captures how I often feel in the midst of a world beset with sadness and pain—a sadness that always seems to come back, no matter how far off into the country I go. Over a languid beat, Ritter addresses the “man on a horse,” laying his soul bare: “Makin’ the best of a bad time/ I’m thinkin’ of you all the damn time/ I must love the pain/ I keep it all to myself/ Sometimes I’m in Heaven, sometimes somewhere else.” Ritter realizes that most of us live our lives in the space between the metaphorical freedom of the country and the drudgery of the everyday. Importantly, the album ends with these lines, “You come to save me, my man on a horse is here.”

Whatever or whomever this “man on horses” symbolizes, Ritter makes one thing clear: if salvation exists, it will meet us in the messy complications of our lives, not in some far off country or on a lonely mountaintop. Whether neat or on the rocks, that’s the kind of sermon I can get behind.

For further reading check out my friend Blaine’s take on Sermon on the Rocks over at Christ and Pop Culture.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply