https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MQshyrB_sD8

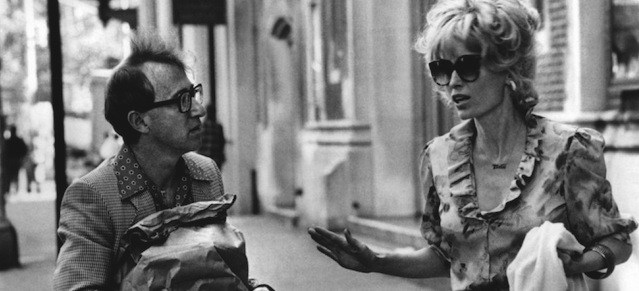

It may be the single greatest Thanksgiving film ever made, yet Broadway Danny Rose is something of an anomaly in Woody Allen’s filmography. Released 1984, it came smack dab in the middle of his golden period (1977-1992), right after Zelig and just before The Purple Rose of Cairo, when Woody could do no wrong. His increased confidence as an actor and filmmaker showed itself in his decision to vary his character more than he ever had before, or since. Instead of a conflicted-yet-talented college-educated neurotic, Woody plays a long-suffering, working-class hustler, a guy who just can’t catch a break (and you can see why) working as an agent for end-of-the-line nightclub acts. Mia Farrow also plays against type as Tina, the heavily hairsprayed ex-girlfriend of a mafioso.

Most of the acts Danny handles are hah-hah ridiculous–a one-legged tap dancer, a blind xylophone player, a stuttering ventriloquist–yet as the film goes on, we see that these people are more than his clientele, they are his family. His motley crew of fifth tier talent represents the absolute dregs of showbiz, yet Danny is fiercely loyal to them all. You might even say he loves them–despite their propensity for leaving him as soon as they experience the slightest success. Danny Rose is a doormat; he gives and gives and gives and never gets back. See where I’m going with this? In an essay for The Guardian, writer Alan Pulvar proclaimed:

What other culture would see the heroism in such an apparently inconsequential failure of a human being? Danny Rose is useless in a fight, can barely run up a hill without being sick, is a loser in business, is deserted by all except those even more troubled than him. But he is unquestionably a beacon of hope in a moral wasteland – because of, not despite, his refusal to take other people on.

Of course, Danny is no full-fledged Christ figure; Woody can’t help but play up his cowardice for comic (and, later on, tragic) effect. Yet it remains a compelling characterization, especially when you consider the end of the film, which is the even more anomalous and, for our purposes, relevant element here.

[Spoiler Alert] The plot follows Danny and Tina as they flee the mob, risking their lives in service of Danny’s most beloved client (and Tina’s boyfriend), crooner Lou Canova. As the couple traverses an escalating series of memorable (and gorgeously shot) set pieces, it becomes clear how boundless Danny’s devotion to Lou is. So when Lou, at Tina’s behest, unceremoniously dumps Danny at the close of their adventure, the shock and hurt on Danny’s face is palpable.

Months later, and despite her boasts about having no time/use for guilt–not to mention her repeated “you gotta do what you gotta do” motto–Tina finds herself plagued by the betrayal she instigated, unable to sleep. She severs ties with Lou, but that doesn’t seem to help. Cut to Thanksgiving Day, with Danny hosting his annual “frozen turkey” dinner for oddballs and strays (truly a communion of sinners a la Luke 14:15-24):

We admire Woody Allen’s films for many reasons: the humor, the existential anxiety, the strong female characters, the terrific Tin Pan Alley music, the emotional honesty, the overall tastefulness, the exquisite cinematography. Mercy in the face of deserved judgment, though, is not usually on the list. Neither are forgiveness, absolution or reconciliation. Yet here we are.

Woody’s gone on record about how proud he is of the melancholy conclusion to The Purple Rose of Cairo, and how much he wishes he’d stuck to his guns on the original, more downbeat finale to Hannah and Her Sisters. But for my money, the closing minutes of Broadway Danny Rose has them both beat, philosophically and artistically. In fact, while it may not ultimately be his greatest film (it’s up there), it makes a strong case for being the greatest ending. After all, it’s relatively easy to go out on a believably dour note; an authentically hopeful ending on the other hand, one that doesn’t resort to the feel-good triumphalism that tends to pass for redemption in Hollywood (glory!) but instead locates the very real grace that can flow from a defeated person–and does so without any words–well, that’s a lot more difficult.

Was it Ted Turner who said “Christianity is a religion for losers”? I’m not sure, but I know for a fact that it was Danny’s Uncle Sidney who said, “acceptance, forgiveness and love.”

Bonus Track: A seasonally appropriate sermon on “The Mother of All Virtues”:

COMMENTS

One response to “From the Archives: Betrayal and Grace Over Frozen Turkey”

Leave a Reply

Great article on a modern classic. Thx!