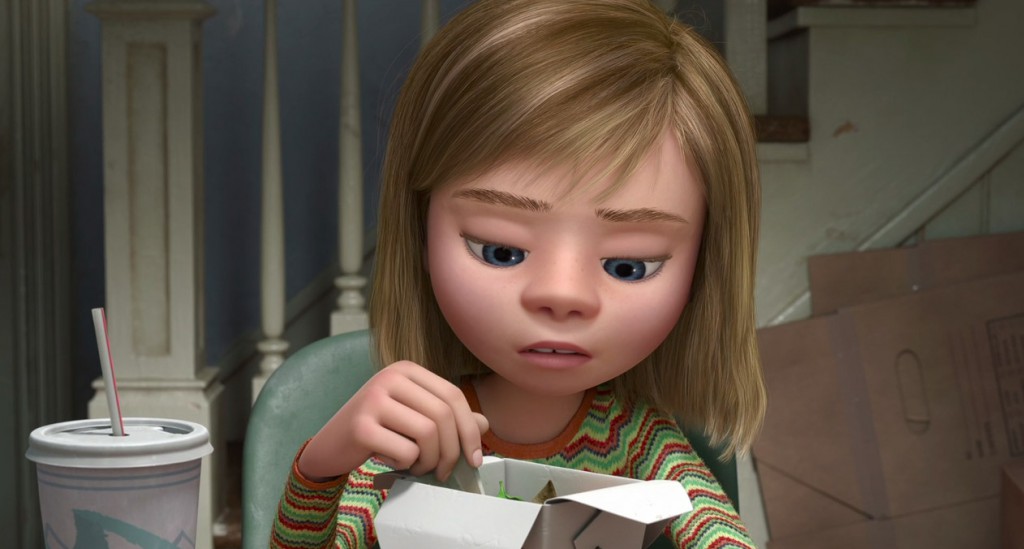

Sadness is having a cultural moment, and that makes me happy. Much of this is thanks to Pixar’s Inside Out, that rare film which deserves all the success and acclaim being heaped upon it.

There are any number of reasons to laud the movie, as DP pointed out a couple weeks ago. Its artistic merits are beyond question, but so are those of, say, The Box Trolls (seriously!). What makes Inside Out so remarkable is its message. Pete Docter, et al, are saying something that strikes the almost impossible balance of timely, courageous, and, well, true. Which is that sadness, grief, loss are not “bad” but necessary for healing and growth. We stigmatize them at our own peril.

The film itself does more than simply communicate this truism, the narrative evokes it emotionally. The Pixar people are experts at misdirection–esp. humor and invention–so that before you know it, you’re tearing up and feeling the very grief (over the passage of time if nothing else) that the film is exalting. You walk away basking in catharsis, very much akin to Louis CK after a roadside rendition of “Jungle Land.”

For the purposes of this site, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that Docter does something uncanny in his diagnosis. Joy does more than simply stigmatize Sadness; she legislates against her. In a brilliant gesture of superego, Joy draws a circle around Sadness and tells her she is not allowed to leave it. The internal “ought” is clear: Thou Shalt Never Feel Bad. Or, more generously, Thou Shalt Only Feel Bad In Precisely Circumscribed Ways. It probably doesn’t come as a spoiler to report that the tactic backfires. Sadness and Joy are exiled together–you can’t have one without the other (not unlike how we talk about Law and Gospel)–and when Anger, Disgust, and Fear are left alone to drive the train, emotional death is a foregone conclusion.

In other words, at the bottom of Riley’s crisis, lies the dynamic of internal ‘ought’. Where exactly this mandate derives from is unclear. Part of it has to do with the role Riley (the child) has come to play in her family. What begins as her parents’ affectionate description of her–“our happy girl”–turns into a set of shackles when adversity rears its head. It becomes something she feels she has to be for her parents. The religious parallel should be self-evident. The moment that being a Christian entails exhibiting a specific set of emotions is the moment that failure and burnout become inevitable.

And yet, the film does not blame the parents exclusively for Riley’s internal predicament. Her parents lie at the heart of so many of her happy memories. That’s a great thing. Plus, Joy only seems moderately interested in pleasing them. It would appear that there is something about the actual mechanics of Riley’s brain/heart that resists negativity. The memories construct a life-narrative that demands adherence. The law is written into the programming itself, if you will, and the mode by which the architecture adjusts looks a whole lot like death and resurrection.

Alas, I’m pretty far afield from the original purpose of this post. I meant for it to be a prelude to the article that appeared on Slate this past week, about Helicopter Parenting Being Increasingly Correlated to Depression at College, ht WTH. The piece was adapted from Julie Lythcott-Haims’ new book, How to Raise an Adult: Break Free of the Overparenting Trap and Prepare Your Kid for Success, which David Brooks and Bill Deresiewicz lauded in their Aspen talk last week (and which we wrote about recently here). Lythcott-Haims is less concerned with restrictions on sadness, as she is the refusal to let our kids feel bad more generally. She relates a ton of recent research, as well as a few stories that are borderline unbelievable. Laugh or you’ll cry:

One kid’s father threatened to divorce her mother if the daughter didn’t major in economics. It took this student seven years to finish instead of the usual four, and along the way the father micromanaged his daughter’s every move, including requiring her to study off campus at her uncle’s every weekend… Later this student told me, “I pretty much had a panic attack from the lack of control in my life.” But an economics major she was indeed. And the parents got divorced anyway.

In 2013 the news was filled with worrisome statistics about the mental health crisis on college campuses, particularly the number of students medicated for depression. Charlie Gofen, the retired chairman of the board at the Latin School of Chicago, a private school serving about 1,100 students, emailed the statistics off to a colleague at another school and asked, “Do you think parents at your school would rather their kid be depressed at Yale or happy at University of Arizona?” The colleague quickly replied, “My guess is 75 percent of the parents would rather see their kids depressed at Yale. They figure that the kid can straighten the emotional stuff out in his/her 20’s, but no one can go back and get the Yale undergrad degree.”

In a 2013 survey of college counseling center directors, 95 percent said the number of students with significant psychological problems is a growing concern on their campus, 70 percent said that the number of students on their campus with severe psychological problems has increased in the past year, and they reported that 24.5 percent of their student clients were taking psychotropic drugs. In 2013 the American College Health Association surveyed close to 100,000 college students from 153 different campuses about their health. When asked about their experiences, at some point over the past 12 months:

- 84.3 percent felt overwhelmed by all they had to do

- 60.5 percent felt very sad

- 57.0 percent felt very lonely

- 51.3 percent felt overwhelming anxiety

- 8.0 percent seriously considered suicide…

When parents have tended to do the stuff of life for kids—the waking up, the transporting, the reminding about deadlines and obligations, the bill-paying, the question-asking, the decision-making, the responsibility-taking, the talking to strangers, and the confronting of authorities, kids may be in for quite a shock when parents turn them loose in the world of college or work. They will experience setbacks, which will feel to them like failure…

Although we overinvolve ourselves to protect our kids and it may in fact lead to short-term gains, our behavior actually delivers the rather soul-crushing news: Kid, you can’t actually do any of this without me…

Knowing what could unfold for our kids when they’re out of our sight can make us parents feel like we’re in straitjackets. What else are we supposed to do? If we’re not there for our kids when they are away from home and bewildered, confused, frightened, or hurting, then who will be?

Wowza. I believe it was Martin Luther who claimed that unbelief was the root of all sin, even/especially the ones that the culture has baptized. Of course, this kind of functional atheism is not confined to non-religious circles, not remotely. It’s simply what happens when Fear is the only one at the controls. No wonder the character in the film collapses when he’s left alone at the bridge. In fact, if I have any criticism of Inside Out, it’s that Fear plays too small a role. Fear of sadness is what motivates Joy to overcompensate, does it not? Perhaps Fear would play a larger role if the protagonist were a bit older.

Indeed, the what-if’s of Inside Out are pretty fun. In Lythcott-Haims’ version of the film, the parents wouldn’t have moved Riley to San Fransisco in the first place because a bigger pool of kids would mean a higher probability of failure, and they wouldn’t want to risk hurting Riley’s chances of getting into a top-tier college. Those schools are swamped with applications from both coasts as it is. Better to leave her in Minnesota where she can excel (and where outside factors are easier/less expensive to control). Alas, then Riley would have never had the opportunity to deal with the loneliness and fear and sadness that proves the stepping stone to her maturation.

If there’s a grace note here, it’s the one that the film already strikes. Joy is forced to give up her controlling ways. Grace doesn’t manage. It pardons. It knows that grief is a doorway, not a brickwall. In other words, God is not interested in what we think we should feel but in what we actually do. He is not found apart from failure, rejection, sadness and loss, but in it (e.g. Bing Bong). To make an enemy of grief is to make an enemy of the cross.

It is no small comfort then, that God is in the business of loving enemies. I hear he’s even been known to chase down runaways–their parents as well.

COMMENTS

4 responses to “Thou Shalt Never Feel Bad: Inside Out for the Ivy League”

Leave a Reply

Great piece on a great film! It struck me that in the mom’s hq department, Sadness sits in the chief operating seat, while in Dad’s hq, it’s anger. The notion that sadness is a key component in the dynamic of love because it facilitates empathy is, I think, insightful. How funny that, in the kid’s mind, moving to San Fran from the midwest is a bummer, so the opposite of perhaps what many adults might think about such a move. But, as you mentioned, clearly “avoiding negativity” often becomes a justification for denial. Thanks, DZ! You’re on a roll recently. 🙂

Isn’t it amazing, that in many Christian circles, ‘negativity’ is something to be prayed away/commanded to leave? How would we learn and grow, if there are no mistakes/failures/sadness, etc..? And how would we know the grace of forgiveness, if there were no sin to be forgiven? Well done, David Zahl!

Really good article here, and a lot to digest. I was a bit surprised that your article didn’t mention that Docter is a Christian. He’s said that he doesn’t ever plan to do a film that’s explicitly Christian, but rather that he wants his faith to show through in the stories that he tells. Watching Inside Out I definitely thought I could see several times the film was influenced by his faith, several of which you noted here.

This is an amazing post. We saw the movie this weekend! Wow!