It’s no secret that here at Mockingbird we like to talk about how the themes of Law and Grace play out in everyday life, so much, in fact, that there’s now a Mockingbird publication which bears its namesake.

When we say “law”, we tend to mean that the posture of the self in some way fails to be truly at rest. As the Glossary puts it,

In practice… the requirement of perfect submission to the commandments of God is exactly the same as the requirement of perfect submission to the innumerable drives for perfection that drive everyday people’s crippled and crippling lives (you should be successful, you must be skinny, you ought to be happy, etc). You might say that divine demand upon the human being is reflected concretely in the countless internal and external demands that we devise for ourselves, religious or not. Everyone is subject to it.

So “law” often takes the form of command, accusation, or rule in which the self has to shore up its own energy, and the effects of that are anything but life-giving. On the other hand, grace is something that comes to us from the outside (extra nos), from God Himself, in which the human receives all that he has. It is not something that man must earn or can even find; rather, grace is totally free and invests its recipient with beauty and worth. And because the human is by definition a social being made in God’s image (Gen. 1:26-27), grace too can be mirrored in everyday life from human to human.

So “law” often takes the form of command, accusation, or rule in which the self has to shore up its own energy, and the effects of that are anything but life-giving. On the other hand, grace is something that comes to us from the outside (extra nos), from God Himself, in which the human receives all that he has. It is not something that man must earn or can even find; rather, grace is totally free and invests its recipient with beauty and worth. And because the human is by definition a social being made in God’s image (Gen. 1:26-27), grace too can be mirrored in everyday life from human to human.

One of our favorite theologians from history, the Reformer Martin Luther, self-consciously placed the proper distinction between Law and Gospel high on his list of theological insights. Only a cursory survey of quotes from Luther’s Large Galatians Commentary makes clear how important he understood this proper distinction to be: “Therefore whoever knows well how to distinguish the Gospel from the Law should give thanks to God and know that he is a real theologian.” Again, he writes, “The knowledge of this topic, the distinction between the Law and the Gospel, is necessary to the highest degree; for it contains a summary of all Christian doctrine.”

The English Enlightenment philosopher John Locke apparently picked up on this insight, namely, that there must be a distinction of categories, though he referred to them as the “law of works” and the “law of faith.” That both bear the name “law” might be a trivial matter if it were not for his exposition of the two. In The Reasonableness of Christianity, he writes,

[T]he difference between the law of works, and the law of faith, is only this; that the law of works makes no allowance for failing on any occasion. Those that obey are righteous; those that in any part disobey, are unrighteous, and must not expect life, the reward of righteousness. But by the law of faith, faith is allowed to supply the defect of full obedience; and so the believers are admitted to life and immortality, as if they were righteous.

The proper distinction, then, amounts to this for John Locke: the “law” requires absolute perfection and its ironclad rule cannot be abated; on the other hand, the “gospel” (AKA “the law of faith”) makes room for a supplement to be added for those who believe what God says to be true. That is why Jesus Christ, the long expected Messiah, must come. In his words,

God dealt so favorably with the posterity of Adam, that if they would believe Jesus to be the Messiah, the promised King and Saviour, and perform what other conditions were required of them by the covenant of grace, God would justify them because of this belief; he would account this faith to them for righteousness, and look on it as making up the defects of their obedience; which being thus supplied by what was taken instead of it, they were looked on as just or righteous, and so inherited eternal life….

…[A]nd so their faith, which made them be baptized into his name (i.e. enroll themselves in the kingdom of Jesus the Messiah, and profess themselves his subjects, and consequently live by the laws of his kingdom) should be accounted to them for righteousness; i.e. should supply the defects of a scanty obedience in the sight of God; who, counting this faith to them for righteousness, or complete obedience, did thus justify… and thereby capable of eternal life.

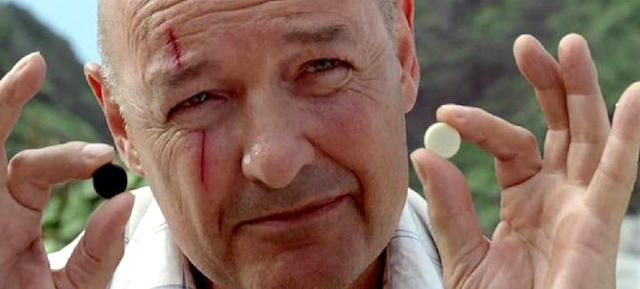

So what does all this about John Locke have to do with anything in the 21st Century? Well, everything really, for this is precisely what we do not mean by Law and Gospel. Locke envisions Christianity primarily in terms of law-keeping. To be human, in Locke’s eyes, means to measure up to the standard, but sin has rendered that a tough project on man’s part. Thus, grace is all about a supplement, so Jesus is there to supply what is lacking. He has to give us that little bit of extra, that extra oomph to cross the finish line, the Red Bull to help us reach God that Great “Law-Giver”. Might it be that this is the message that American religion often substitutes for what the Reformers saw as central to Christianity?

Unlike Locke, Luther defines God not primarily as the “Law-Giver” but as the Self-Giver, which is expressed most chiefly in Christ’s incarnation, death, and resurrection. God in Christ is now the source from which the Christian derives his entire being: “…[W]ith Christ living in him, he lives an alien life. Christ is speaking, acting, and performing all actions in him; these belong… to the Christ-life,” says Luther. In the death and resurrection of Jesus, God has at last dissolved the identity of the old man and established himself as God. Christ is the New Man who has come to recapitulate the world in his image, for he is making all things new. “Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation. The old has passed away; behold, the new has come” (2 Cor. 5:17).

COMMENTS

10 responses to “When John Locke Turned Gospel Into Law”

Leave a Reply

“In practice… the requirement of perfect submission to the commandments of God is exactly the same as the requirement of perfect submission to the innumerable drives for perfection that drive everyday people’s crippled and crippling lives…”

This is an oversimplification which actually serves to confuse the law/gospel distinction, at least as St. Paul saw it. The result is that upper middle-class performance neurosis is conflated and confused with true moral guilt. When all “law” is lumped into the same category, whether it be “look gorgeous at all times” or “love your neighbor as yourself”, this invites all “law” to be seen as unfairly demanding things of me that I cannot attain. Lumping God’s law to love into the same pot with my parents’ demand that I get into Harvard, or my friends’ expectation that I maintain a thigh gap, leads me to have the same negative emotional reaction to both. We can repeat the mantra that “God’s law is good” all we want, but when we conflate any and all “demand”, call it all “law” and claim that “in practice” it is all the same, we are bound to see God’s law as our enemy that is at war with God’s grace. For St. Paul, God’s law is not only perfect, but good, and it is our own wretched selves, not God’s good law, that makes the law death for us. As St. Paul says in Romans 7:

12. So then, the law is holy, and the commandment is holy, righteous and good.13. Did that which is good, then, become death to me? By no means! Nevertheless, in order that sin might be recognized as sin, it [my sinfulness] used what is good [God’s law] to bring about my death, so that through the commandment sin might become utterly sinful.14. We know that the law is spiritual; but I am unspiritual, sold as a slave to sin.

Michael, I think you raise a good point, and it is one which I continue to ponder. I see using “law” for everyday identity-issues as a way to contemporize the message of sin and grace for a new day; because of the way I understand original sin, I do think that all religious and non-religious postures are a participation in the demonic if not grounded in the Triune self-giving. Outside of Eden, we are now bound and forced to retreat to ourselves. I might also add that, at the moment, I see it as a way of speaking Law And Gospel for a different audience beyond what Paul may have directly meant to his Roman (and Jewish?) audience. Would you say that your main concern is the nomenclature?

This is a good (and important) discussion, Michael. Mockingbird’s book, Law & Gospel, differentiates the two kinds of law: little “l” law includes those things we place on ourselves or others and big “L” Law is God’s moral law.

It seems like trying to follow and measure up to the little “l” law reveals our performance-driven hearts, but we are only required to perfectly obey the big “L” Law. Thus, it is important to make the distinction.

My concern is not with nomenclature. We don’t need to and probably should not use the words “sin” “holy” “spiritual”, etc. at all, at least initially, but the words we do use should accurately convey the message that the apostles gave. But if we use modern analogies that lead to the conclusion that our fundamental problem is that we are all victims of the “law”, whatever it’s form, and that “grace” rescues us from the mean, spirit-killing “law”, then we are teaching a “gospel” that is much closer to that of William Blake than that of St. Paul, in my view. I say that as one who thinks that all the “purity rings” in American evangelicalism should be melted down and cast into phallic totems, where they would do less harm to the gospel message.

“Might it be that this is the message that American religion often substitutes for what the Reformers saw as central to Christianity?” The answer is an unqualified yes, and has been ever since our founding. Evangelicals, because of their self-conceits of holding a supposedly pristine faith, have been blinded to their partial origin in the Enlightenment, and hence, thinkers like Locke. This is not to engage in fundie-bashing so much as to illustrate the poverty of Anglo-Saxon rationalist influence upon Christian theology. I think learning the historical conditioning of English-speaking Protestant thought and understanding the barriers between that and the Germanic tradition (not merely Lutheranism, but also the early Reformed tradition emanating from the Heidelberg Catechism, and so on) will yield important insights here, in that one will, on a close reading, find the Westminster Confession placing Presbyterianism closer in some ways to Locke than Luther. As some have remarked before, the British mind is almost incurably Pelagian, and with the English language came a ruthless determination to justify ourselves as an American people. I would advise Mr. Cooper to keep that in mind while offering an otherwise needed corrective to the antinomianism he perceives in Mr. Bennett’s stance.

“…for this is precisely what we do not mean by Law and Gospel.” Love that. And I totally agree. That can’t be “the Gospel”. The only problem is that I found your explanation of what the Gospel actually is to be rather hard to internalize. It still feels as though I should be doing something more that I’m not doing in order for Christ to fully live in me. It feels like the alternative to worrying about what I’m supposed to be doing is to just forget about worrying about what I “should” be doing and then just blame God if/when I’m not living up to the standard? You can see how I’m struggling with this… (yes, I clearly need to read the new Mbird book.)

Moreover, were I a minister, I feel like I might struggle with understanding how to expound upon Christ’s very clear moral vision for human lives (let’s not call it a “law”) in sermons without dipping back into the “you should do this” and “you should not do that” territory… This is really complicated stuff, honestly.

“the British mind is almost incurably Pelagian”

Hmm. Nice generalization, thanks.

I think the problem with this interpretation of law = sin, as you expound it, is that you are overemphasizing the negative aspects of the law while ignoring the positive aspects attributed to it by the Biblical authors. This is what opens up the accusations of antinominalism; by equating “sin” with “law” you render it impossible to convey that the law of the old testament had an actual purpose created by God that was meant to be good, just, and that it was considered a blessing. It was hardly God’s complete and sufficient plan, but when reading these articles it just often sounds like the law just needs to be burnt.

I also sympathize with Benjamin… it’s difficult to practice the difference between doing things because you should and doing things because of joy residing in grace. Years go by and we sometimes wonder when and where the transformative Holy Spirit will act. Personally after having nothing happen I’ve wondered whether my problem was that I wasn’t accepting God’s grace *enough*, and if I just accepted it more then God would finally change me and everything else would fall into place. When I told this to my pastor he said “wow, you’ve even turned God’s grace into law!” So tempting it is to fall into the pattern of “I do X to get Y.”

It would be interesting to see how you interact with “sin is lawlessness”, from 1 Jn 3:4. I’m reminded of how learning to make beautiful music starts out with legalism: follow the notes rigorously, play your scales precisely, rinse and repeat. These ‘laws’ never become obsolete so much as become flexible in a limited fashion. The purpose was never to satisfy them more and more perfectly; the purpose was to create beautiful music.