This one comes to us from Caleb Stallings:

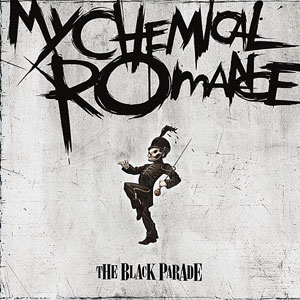

Recently, I found myself listening to a favorite band from my adolescence: My Chemical Romance. I know, I know… The certifiable kings of emo rock! I should be embarrassed by this, right? Some people certainly think so. When I mentioned my appreciation for them recently on Facebook, I was met with an immediate and sarcastic reply, “So are you gonna start painting your nails black now?” The response got me thinking about why I used to (and still do) find MCR compelling. I can hardly think of a more vilified band from my teenage years, yet even now in adulthood, I feel the need to defend their legacy. And nowhere does that need present itself more clearly than with their third album and magnum opus: The Black Parade.

Recently, I found myself listening to a favorite band from my adolescence: My Chemical Romance. I know, I know… The certifiable kings of emo rock! I should be embarrassed by this, right? Some people certainly think so. When I mentioned my appreciation for them recently on Facebook, I was met with an immediate and sarcastic reply, “So are you gonna start painting your nails black now?” The response got me thinking about why I used to (and still do) find MCR compelling. I can hardly think of a more vilified band from my teenage years, yet even now in adulthood, I feel the need to defend their legacy. And nowhere does that need present itself more clearly than with their third album and magnum opus: The Black Parade.

It’s been several years since I listened to this album in its entirety (sadly, I somehow think this has to do with what Dave Grohl once described as a “residual punk rock guilt,” which weighs on all of us who are trying to be cool in the midst of liking uncool music). But within seconds, I remembered why I so cherished this record. That transcendent pleasure of musical frisson sent chills down my spine as the ever-intriguing frontman, Gerard Way, triumphantly sang, “Because one day / I’ll leave you / a Phantom to lead you in the summer / to join the Black Parade!” The swell of marching band percussion and the wail of dual guitars reminded me that I was not in some emo-fied bedroom mope session. No, instead, the curtains had been drawn, and I found myself face-to-face with the ominous and inevitable march of the Black Parade, the band’s not-so-subtle metaphor for death. And it’s that very lack of subtlety that seems to be the cardinal sin of which the band is often accused. However, it’s precisely the melodrama that makes the album so successful. There’s no room for emotional reticence in the way of The Black Parade, and in an era where obscurity often masquerades as profundity, MCR’s intentional theatricality seems like a breath of fresh air.

When I talk to naysayers about this album, I always start by drawing their attention to the fact that it’s more or less a rock opera, that is, an album with a cohesive narrative and point behind it. The album’s main character, simply known as “the Patient,” is a man reflecting on his short life while facing imminent death. This character is prominent in the music video “Welcome to the Black Parade,” where he is surrounded by the band in Sgt. Pepper’s-like marching band personae, only in greyscale. And what an extravagant video it is! We move from a crowded and despairing hospital death bed to what looks like the set of a silent movie telling a post-apocalyptic tale, complete with warped film stock and common cinematic flourishes of the time (closing irises, fast projection speed, etc.). But what’s truly striking about this track, as well as the album, is the honest and emotional whiplash we experience throughout it. Gerard Way, and consequently the Patient, refuses to slip into death; he marches towards it. As the Patient protests his dying in “Cancer”, we hear:

Now turn away,

‘Cause I’m awful just to see

‘Cause all my hairs abandoned all my body,

Oh, my agony!

Know that I will never marry

Baby, I’m just soggy from the chemo

But counting down the days to go

It just ain’t livin’…

The song is intensely melodramatic, especially in its description of chemotherapy, and for that very reason, it feels oh so real. I’m reminded of theologian Todd Billings’ recent remarks on his own terminal cancer in his book, Rejoicing in Lament: “Thus while the psalmist does not assume an afterlife… nevertheless an early death is grounds for protest and lament.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XAcj_armFos

The song “Mama” accomplishes something similar in recalling the horror of participating in war and taking the life of another: “But the s—t that I’ve done with this f— of a gun / You would cry out your eyes all along / We’re damned after all / Through fortune and flame we fall.” It doesn’t matter that the song has a jaunty circus tune, a Freddie Mercury-like flare, or the backing vocals of Liza Minnelli(!): it’s an absolute horror, as the operatic arrangement makes clear. Again, the histrionics throughout the album are surprisingly relatable, even appropriate; if there’s any subject that calls for them, it’s this one. The very place where MCR is so often accused of going wrong is exactly where they go right.

But The Black Parade is so much more than a sensationalized account of death. In fact, it’s nothing if not a religious account. The opening track, “The End,” invites us to witness the tongue-in-cheek repentance of the Patient: “You’ve got front row seats to the penitence ball,” followed by a more somber, “(Save me!) Get me the hell out of here / (Save me!) Too young to die and my dear / (You can’t!)” It feels like a realistic encounter with death in that it is highly conflicted.

Through the eyes of the Patient, we see a man that crosses back and forth between Invictus-like resolve and hand-to-Heaven revelation depicted in the video for “Welcome to the Black Parade”. This is the ebb and flow of Way’s own reflections on death: obstinate resignation to fearful plea. And although the overall implication of the record is gleefully and almost maniacally nihilistic (“If life ain’t just a joke / Then why are we laughing? / If life ain’t just a joke / Then why am I dead?”), it’s fascinating that Way can never really cast off the language of faith. The preamble of “Welcome to the Black Parade” sounds vaguely Messianic, after all:

He [my father] said, “Son when you grow up,

Would you be the savior of the broken,

The beaten and the damned?”

He said “Will you defeat them,

Your demons, and all the non-believers,

The plans that they have made?”

Ultimately, the Patient’s journey terminates in the vaguely hopeful finale, “Famous Last Words”. After all the conflicted reflection of his passing moments, Way belts out, “I am not afraid to keep on living / I am not afraid to walk this world alone / Honey, if you stay, I’ll be forgiven / Nothing you can say can stop me going home.” He hopes for a grandiose and romantic absolution of his sins that will allow him to “go home”. While the sentiment is both charming and heartfelt, one can’t help but echo singer Peggy Lee and ask, “Is that all there is?”

In the end, I’m reminded of the good news of which Paul reminds the Corinthian church, “The last enemy to be destroyed is death” (1 Cor 15:26). Death is not the welcoming arms of The Black Parade, as Way posits. Ironically, even he seems to understand that death points beyond itself. I’m reminded of what Paul describes earlier in that letter: “But in fact Christ has been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep. For as by a man came death, by a man has come also the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive” (1 Cor 15:20-22).

I admire MCR’s empathetic struggle with death. Nearly ten years after its release, The Black Parade’s emotional range is striking, and its melodrama resonates. The record deserves better than its authors’ reputation suggests. It deserves investigation as meaningful music. Who knows, such investigation might lead to a more hopeful answer than the one the record settles on: the non-subtle truth that, on account of the one who lived, and died, but lives again, the Black Parade is not the only leg of our journey.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply