Heads-up: While I do my best to minimize them, if you’re concerned about spoilers, rush out now and see the film.

“My name is Max. My world is fire and blood.” The film’s opening words declare an existence that is already hell, life and death hardly distinguishable under universal wrath. Small pockets of humanity, if not civilization, persist within the wastelands, the scraps of the Before Time (an Edenic memory of our world) savagely contested among desert warlords and their gangs of deranged motorheads. Ordinary folk are complicit, brutalized or both. Max himself, tormented by visions of loved ones whose lives he could not save, summarizes his creed in a single word: survive.

I did not head to George Miller’s long-awaited new Mad Max picture because I thought it might contain some intimation of the Gospel. I wanted an afternoon of screeching, post-apocalyptic mayhem, and was not in any way disappointed. That desire was sated and then some. Driving is not, as a rule, interesting to me, but post-viewing to sit behind a wheel and hear a revving engine was practically a spiritual experience.

It wasn’t the Gospel that I sought, but in some twisted measure it was what I observed. The degree to which the film invites conversation with the Christian message surprised, but perhaps it should not have. Post-apocalyptic settings often lean on Christian themes and symbols. Though Miller has not described himself as traditionally religious, his films have provoked such observations before. 1998’s surprisingly dark Babe: Pig in the City includes a remarkable example of violence overcome by forgiveness, and is worthy of theological exploration in its own right.

Fury Road, an aesthetic hymn to early 80s metal albums and Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia, plays out as a relentless, brutal and magnificently executed two hour chase scene and road battle, but under the hood, all is worship. Every character is a viator, a pilgrim, driven by some higher motivation–except, perhaps, for Max (Tom Hardy, ably reproducing Mel Gibson). Immortan Joe (Hugh Keays-Byrne, who played the villain Toecutter in the original Mad Max), masked and ancient lord of the Citadel, declares himself to the destitute throngs with the words “I am your redeemer,” who makes water (and thus life) literally flow down upon them. Joe is a living god, venerated through a V-8 cult whose priests are his painted Warboys. Fearless in the face of death, they chrome their mouths and shout “I live and die and live again,” before immolating themselves in service to Joe’s will. Even Joe’s glance has power; his word of promise “You will ride forever in Valhalla, shiny and chrome” is assurance of everlasting salvation.

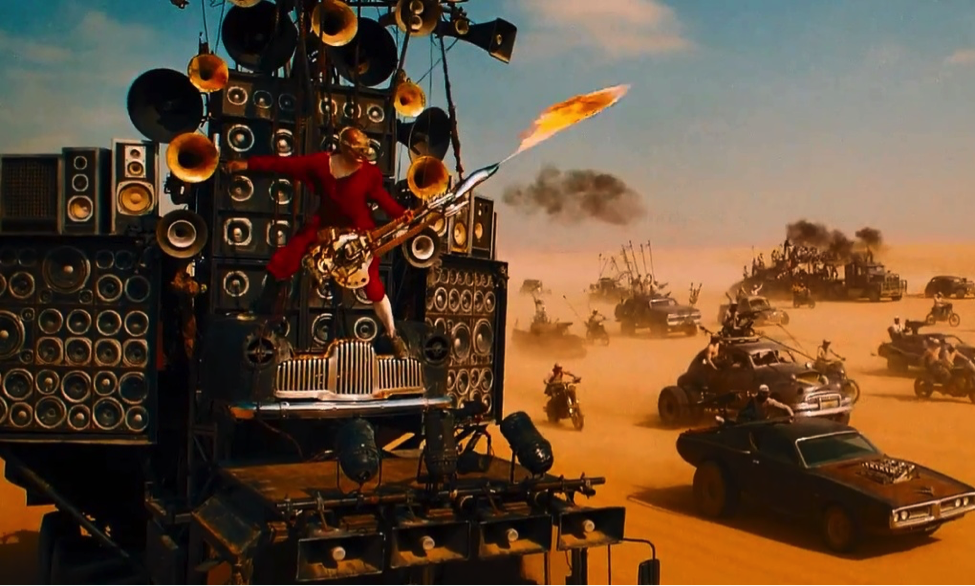

But Joe is a false god, a wicked old man whose young and beautiful enslaved wives flee from him. They will not see their children grow up to be warlords. Assisting is Charlize Theron’s Imperator Furiosa, a trusted commander turned traitor (apostate?), who smuggles them out in a mighty war rig, blasting across the desert towards “the green place,” a faint memory of a world that sustains life. In pursuit are Immortan Joe and his Warboys, their processional marked by the liturgical accompaniment of war drums and a maniacal electric guitarist mounted on the front of an enormous bespeakered truck. Max is with them, a prisoner and “blood bag”, practically crucified on the hood of a war buggy while his blood flows by IV into the injured Warboy Nux (Nicholas Hoult).

The plot of the film, then, is a contest between competing religious visions. Joe and his ilk are the princes of the world as it stands, transparent representatives of a theology of violent glory. Others long for a way beyond the law of this world, that one life can only come at the expense of another. Early in the film, the question “Who broke the world?” is leveled as an accusation, but its answer is hidden. In all likelihood it was no more Joe than Max, Furiosa or the wives. In this world, all are complicit–the seemingly benevolent must learn to snap spines and cover themselves in others’ blood to survive another day.

Just as the breaking and subsequent degradation of the world are left mysterious, so is hope, a word figuring prominently. In a way perhaps typical of our cultural moment, the good guys are somewhat less dogmatically clear in their hope, especially as certain goals prove to belong only to the unrecoverable land of memory. Instead, hope takes sacramental form–water, blood, gasoline and the seeds of green plants.

Max never admits of hope at all. He is unique in this respect. But as others’ hopes flag, Max is there to bolster them, to redirect to a better future, even to offer his own life as their sustenance. A card at the end of the film reads, “Where must we go, we who wander this wasteland in search of our better selves?” It speaks a truth about these characters: Max, Nux and Furiosa in particular. Their better selves aren’t in themselves, but in others. In Max there is only madness and despair for himself, but others draw goodness and life from him. Conversion is possible, redemption is possible–but not from within myself. The bound will does not contain the seeds of its own salvation. A better self, just as a better world, is found outside of me–as we are accustomed to saying, in Christ. In this way the society of sinners proves itself stronger than that of the godly and self-contained. Moments of unexpected poignancy arise as characters demonstrate true one-way love, having encountered others just as broken as themselves.

Max never admits of hope at all. He is unique in this respect. But as others’ hopes flag, Max is there to bolster them, to redirect to a better future, even to offer his own life as their sustenance. A card at the end of the film reads, “Where must we go, we who wander this wasteland in search of our better selves?” It speaks a truth about these characters: Max, Nux and Furiosa in particular. Their better selves aren’t in themselves, but in others. In Max there is only madness and despair for himself, but others draw goodness and life from him. Conversion is possible, redemption is possible–but not from within myself. The bound will does not contain the seeds of its own salvation. A better self, just as a better world, is found outside of me–as we are accustomed to saying, in Christ. In this way the society of sinners proves itself stronger than that of the godly and self-contained. Moments of unexpected poignancy arise as characters demonstrate true one-way love, having encountered others just as broken as themselves.

Each character, without fail, is bound. As the drama of redemption plays out, bondages are revealed and false hopes denied. Death does its work. But true redemption and true hope do not attempt to escape death. At a critical moment, Max interrupts the false hopes of his compatriots and reorients them toward what would seem madness: not to ride off into the sunset, but to turn directly into the face of the enemy and to pass through death to life. No easy ascension into heaven takes place–the religious journey is finally cut off, and life, if it is to come, must come by resurrection.

And Max Rockatansky? Redeemer is a thankless job, and after all he is not quite Jesus Christ. He saved others; he cannot save himself. As before, Max fades away into memory and legend, still wandering the roads like us.

COMMENTS

7 responses to “Water, Blood and Gasoline: The Full-Throttle Gospel of Mad Max: Fury Road”

Leave a Reply

SO glad you mentioned Babe Pig in the City. Feel like I’ve been a voice in the wilderness on that one.

Really odd how unrecognized it went, even though it snuck onto a bunch of critics’ best of year lists.

Let the record show that Pig in the City was the last movie that Gene Siskel named best of the year.

I think you the head of the nail squarely with themes of redemption and finding life outside of oneself. But the depth of some of this is found in the whole metaphysics of the movie. Here are some thoughts:

*More Spoilers*

I think one of the striking scenes is where Immortan Joe shuts off the Water only after a few seconds of letting it run. He bellows to the crowd: “Do not let yourself become addicted to water”. Why is this necessary? Isn’t the water boundless as it comes from the Earth? Because the Creation, seemingly in a Wasteland, is testifying against the hierarchy. The Water from Underground represents a gracious endlessness, not a restrained totality.

Immortan Joe is a harsh ascetic, hence the steam-punking of Viking religion.

He gives a salvation and a redemption, but, as you said, he’s a false god. He preaches a totality, the world is what it seems and not what it does not (i.e. there’s water under the desert). This is the same vision that Furyosa accepts. Our only salvation is in running.

This is actually the most remarkable thing about the movie. I cannot recall a single movie that actually says that redemption is the answer, not excising the corruption. I can think of dozens of movies where the hero escapes, flees to a new land, a new paradise, or forges some thing new far away from the corrupt. Instead, Max takes them back to the heart. There’s something good (e.g. the people(?!?) in the evil empire. Structure isn’t bad. The problem isn’t kings, but evil kings.

What a win for the concepts of government and authority!

And I love the use of ‘seeds’ throughout the movie. Whether it is in the self-contained gardens of the Citadel (whose name bespeaks enclosure) or in the ‘breeders’ Joe keeps, this is representative of man’s blasphemous attempt to control God’s gift. The Keeper of the Seeds is a prophet of the Creator. Maybe Water is not something to ween off of (a denial of our dependency and humanity), but to enjoy.

Joe, as all false gods, is a hypocrite. He keeps his people starved, yet he gluts himself on ‘mother’s milk’ (like a baby). Even he can’t exorcise the goodness of Human finitude in his quest for control and domination.

Wow, I could go on! Suffice to say, I think the new Mad Max is one of the best tellings of strong, oft neglected, Biblical themes of redemption and the goodness of God’s creation, oozing with grace. Tom Hardy’s contracted for another 4 movies(!), I hope they build on the excellence that was Fury Road!

cal

Thanks, Cal. I’ve now seen the movie twice, and for a film with little dialogue there’s quite a lot in it you can miss. Some good observations there–you’re right about the phrase “addicted to water” and what it means. Lot more that could be said.