1. First off, The Onion has been doing marvelous things lately. Their insight into the human condition is always surprising, especially their sense for all the pressures of social life, how ridiculous they are, and how strange is our reliance on them for identity. Cue Mothershould, their new web series on how to be a better Mom. Our frequent use of scorekeeping as a description of our obsession with metrics and comparison has found its best video example since King of Kong, below:

2. In the dystopian scare department this week, Vicky Price of The Independent reviews a new book by William Davies called The Happiness Industry. Our unprecedented ability to examine human behavior and manipulate the brain in service of the common good (“nudging”) has drawn big money, and if Davies is right, it doesn’t appeal to the best part of our nature:

Davies warns against the alliance that has developed between political authorities and academic researchers as well as those between economists and psychologists. I am usually in favour of interdisciplinary work. But Davies is right when he says that the notion of “happiness” has moved from being, as he calls it, a pleasant add-on, to a measurement useful in the business of making money – and at the expense of increased control over your life.

Look, for example, at the development of the “positive psychology” movement that helps you eliminate unhelpful thoughts. Children may soon be taught “happiness” in schools. Being miserable is no longer socially acceptable. There are now computer programmes designed to influence the way we feel. Face-reading software will soon be able to identify moods. Global firms have “chief happiness” officers. There are experimental “mood-tracking” apps that individuals carry with them on their smartphones, adding to the information which is being collected. We can now predict suicide rates from social media and mobile phone conversations…

This data-led approach to understanding people under the guise of improving our happiness is leading to an expansion of surveillance capabilities to which we acquiesce. Big business and the state are able to condition our responses. So comes a seismic shift in the power balance between the individual and big business and more worryingly, between individuals and the state. We are, it seems, sleepwalking into the world of Larkin’s “Essential Beauty”, in which adverts depict “well-balanced families” but “Reflect none of the rained-on streets and squares”. As Davies implies in this readable, disturbing book, being depressed by the human condition will no longer be socially acceptable, or even an option. The state or big business will soon see to it!

The harnessing of various pictures of happiness by advertising goes way back, but the data revolution seems to have made it easier to target ads to people’s weak spots. Increasing state power and knowledge over how to influence people should be alarming to anyone with a low anthropology, but the more immediate worry is that happiness will become more and more stifling, the well-balanced families and beautiful, successful people making us feel more and more isolated. Louis C.K.’s rant on cell phones is pertinent yet again, and we didn’t get far before The Onion hits a perfect good-life parody yet again.

3. The Atlantic gives us another angle into commercialized aspiration, namely, the beauty industry. Perhaps unsurprisingly, many of the scientific claims made by beauty products lack substantiation. Also, we’re easily taken in by it:

The beauty industry is, of course, massive. It involves everything from teeth-whitening toothpaste to ridiculously expensive shampoo that will transform your hair from “ordinary to extraordinary,” if you believe an advertisement for a product that contains white truffles and caviar and costs more than $60 for an 8.5-ounce bottle. It involves celebrity-endorsed cosmetics, perfumes, and a host of fashion products. And it involves numerous fitness and slimming gimmicks… the beauty industry is a huge cultural force in a tight, symbiotic relationship with celebrities and the celebrity-oriented media. The size and influence of this industry creates challenges for anyone seeking to get to the truth about the products it makes and promotes…

Only a small segment of the public is willing to pay the ridiculous prices demanded by purveyors for purifying snails, insect poison, and nightingale excrement. But these stories help to frame how we think about beauty, and they foster the illusion that celebrity status (and wealth) provides access to magically effective anti-aging treatments. They make it seem as if there is something that can be done.

4. Moving to religion, The Washington Post, a self-described ‘cultural Christian’ names Alana Massey writes with insight on the growing population of religious ‘nones’ and the alternatives to theistic faith out there:

The New Atheism of the early 2000s gave us firebrands like Sam Harris and Richard Dawkins, but as scientists rather than philosophers or organizers, and many believers thought that they misrepresented religion and thus failed to give people much to rally around besides anger at their loved ones. TheSunday Assembly, a self-described “godless congregation,” has made the news lately for its growing numbers, and it is good that people find community there. But its motto of “live better, help often, wonder more,” and its mission “to help everyone find and fulfill their full potential,” leave something to be desired for those who feel the moral stakes are higher in the Christian narrative. Even people raised without religion can be fatigued by this feel-good focus on the self…

But why should cultural Christians bother trying to reconcile with churches? “People very understandably associate religious institutions with very real harm and danger,” Stedman says. “But institutions are also places where people share ideas and where they organize, and heal, and hold each other accountable.”

That’s been especially evident this year in anti-police-brutality organizing, in which churches have served as bases for people to grieve but also to catalyze otherwise disparate groups into meaningful protest. Maguire noted that many people stick with church despite nonbelief because no other communities share their moral passions: “I think we’re in the interim period where we haven’t created the alternatives yet.”…

Believing Christians need not water down the fact that God is at the root of their commitments and traditions to accommodate nonbelievers. And nonbelievers need not make a point of telling their believing brethren that general goodwill or humanism is a better motivation for good works. As Maguire points out, the biblical metaphor for society is a household, not an institution but a dwelling place for a family. Though families will quarrel over what they don’t have in common, they are meant to come together for what they do: an ancient story of a new family formed in a place most of us will never go and a call to peace in the world that none of us can ever entirely live up to. And that is worth keeping alive for its radical, enduring and miraculous love.

This perspective (from our perspective) has lots to commend: a levelheaded, non-angry take on Christianity from a non-theist is something of a pearl of great price. Still, someone going to church merely in search of shared moral passions should, at least every once in a while, be offended – you know, scandalized. The radical, enduring love portion is great, but the skeptic in me can’t help but think such love needs something to ground it – “we love because he first loved us,” as the Good Book saith. But I think any search for common ground is nice, a rare enough thing that bludgeoning churchgoing nones with God’s Wholly Other-ness would be a mistake, at least for now. As Maguire noted, though, we’re in fresh territory: can people find robust meaning and moral urgency without predicating, at the least, a vague ‘Higher Power’? And can moral passion, freed from the shackles of revelation or (at the least) tradition, keep itself from going astray? First question’s up in the air, but I think the second has been more than settled with the nationalistic, ideological, and cultic fervor of the last couple centuries.

5. Speaking of the decline of moral worldviews, David Brooks was absolutely skewered by Albert Burneko for Deadspin. I don’t always love Brooks, especially when he starts to sound like Malcolm Gladwell, but he’s a reliable counterweight to our obsession with success/happiness/individualism/etc, so I’m overall pretty grateful.

Burneko’s article made me like him even more. Burneko looks with a keen eye on Brooks’s op-ed stuff from the last few months, reinterpreting his critiques of the modern world as cries for help from the miserable, insecure, aging man he takes Brooks to be:

David Brooks is telling us something dark and sad—about loneliness and the search for connection; about social desolation and sexual frustration and sadness. Something deeply personal, about discovering, too late in life, that accomplishment and position and thinkfluence are no ameliorative for the rejection of your gross old-man [-ness] by cute millennials. Something not about what priorities he guesses Whole Foods Uncles will take into the voting booth in 2016, but about himself.

Oh God, I don’t think we have been listening.

You can guess where it goes from there: extremely witty and borderline hateful. Brooks struggles with meaning, so he writes about the collapse of it. Brooks struggles with dating, so he criticizes online dating culture for its commodification of people. On Brooks’s divorce,

He is lost. Lost and alone. He misses her so [] much. Her, and the way things used to be…

Such is the confused nature of our modern, technologized relationships, Dave tells himself. Even people in near physical proximity can be separated by cosmic digital distance. We don’t even “like” each other’s Face-Books! It’s like I can’t even fluence your thinks anymore at all.

If you are like me you know a lot of relationships in which people haven’t managed this sort of transition well. Communication that was once honest and life-enhancing has become perverted — after a transition — by resentment, neediness or narcissism.

Dave. No. What did you do. What did you do, Dave?

Would love to quote more, but my radiation badge for unreflective self-satisfaction has hit capacity, thanks to Burneko’s intolerable voice. What Burneko misses (apart from serious engagement with anything Brooks has written) is that it is perfectly okay, even commendable, to write with one’s personality, emotions, and even perhaps weaknesses in mind. Yes, Brooks’s tone can occasionally sound like he thinks he has all the right answers, but I’m convinced by Burneko’s argument that David Brooks has some skin in the game. And that’s a damn good argument for why we should continue listening to him.

https://youtu.be/TjAdWEptHQ4&w=600

6. Speaking of guys worth listening to, Bill Fay’s new album, Who Is the Sender?, is out! I’ll wait on our resident Bill Fay guru for the verdict, but for now there’s Pitchfork’s excellent writeup on Fay’s Christianity and how his music evades the pitfalls of other Christian singers. Here goes:

The gap between Fay’s aesthetic and that of the Jesus music movement may seem minute, and perhaps it is. But the theology that fills that gap is mighty. Fay writes as someone who lives on Earth and wants to see life here improve. He hardly avoids the truth; his staring into the void is the only thing that allows him to mourn its existence. Just as importantly, he longs for the life of the world to come, and he testifies to its quiet creep into the present. “You were born, though you need not have been born here at all,” he sings on Persecution’s “Plan D”. “And is that not some cause for worship, being born among these trees?” Existence—existence in this life, that is—not only matters, but is in itself a blessing, a gift that is inherently good. He writes about nature the same way that the great English poet Gerard Manley Hopkins did; every bird as it arcs and every wave as it crests willfully traces the outline of a mysterious and gracious God.And while that God is indeed going to return, he’s returning to make the world new again, to make human life livable.

As he’s aged, Fay’s ability to articulate the tension between all that is good and all that is bad about human life has sharpened. On Who Is the Sender?, released last week, he shuttles the listener between these two poles so deftly that they begin to lose their distinction. “War Machine” begins with a lulling stroll through a forest—”The hills are alight/ Feels like the first day of your life”—that gently bends into a meditation on the military industrial complex. There’s an ache in Fay’s voice as he implicates himself in his country’s long relationship with war, and it’s only partially resolved by the coda’s benediction: “There won’t always be the war machine.” A few songs later, he’s acknowledging the apparent absence of mercy and hope in the world over a threadbare melody and a sketch of guitar while reminding his listener of an ever-present, ever-shining light.

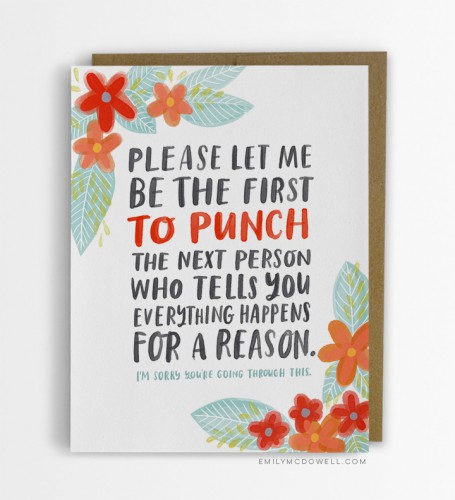

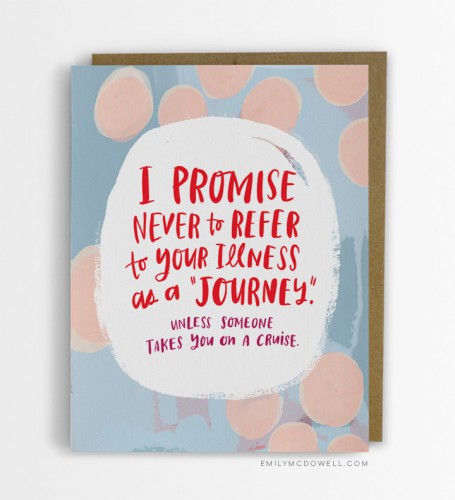

Extras: The empathy cards above come from Emily McDowell, birthmoviesdeath takes a fascinating look at the surprising scarcity of alter egos in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Stephen Colbert funds all grant requests by schoolteachers in South Carolina in a wonderful moment of grace in practice, and Silicon Valley continues to wow.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply