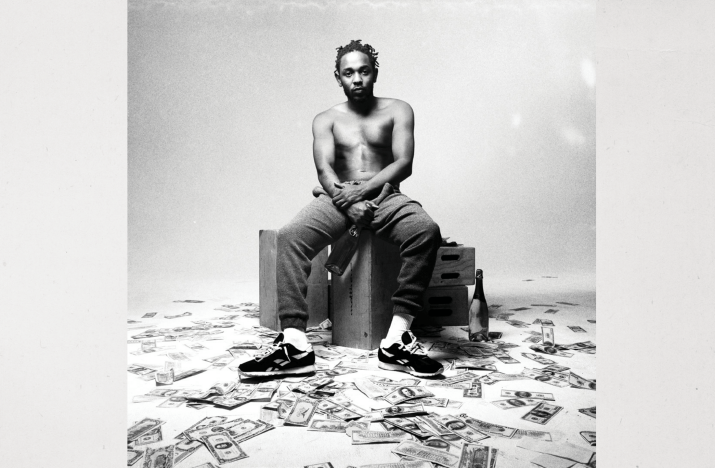

Inside the liner notes of Kendrick Lamar’s new album, To Pimp A Butterfly, is a picture of Lamar (shown above) sitting in a room with assorted dollar bills scattered around him on the floor. Pictures like this are a common and maybe tired rap trope, typically appearing in magazine spreads and liner notes, rife with allegories of success and the spoils of excess that come with it. Lamar’s picture strikes a different chord though. He sits solitary on a crate in sweatpants with untied Reebok sneakers and a bottle of liquor in one hand, his tranquil eyes looking right at the camera. At the heart of the Lamar presented in the picture and on To Pimp A Butterfly is someone more conflicted: a man with tremendous commercial and critical success and yet, fraught with the resentments and temptations of who he’s become. A man caught somewhere between old and new, between caterpillar and butterfly.

To Pimp A Butterfly follows three years after Lamar’s excellent and wildly successful major label debut, good kid, m.A.A.d city. A sprawling and complex concept album with a poem recited by Lamar as its central theme, Butterfly is similar in form and structure to its predecessor, but that’s about where the similarities end. Where good kid was an album journaling Lamar’s childhood upbringing in Compton with the temptations of street life all around him, Butterfly finds Lamar in the present struggling with “survivor’s guilt” and battling the temptations of success in the form of the symbolic character “Lucy” (short for Lucifer). good kid coasted by on breezy underground west coast production, where Butterfly is a smattering of jazzy, psychedelic funk and hip-hop (seemingly inspired largely by Lamar’s collaboration with Flying Lotus last year). This production style gives Butterfly a much looser and rawer feel than good kid, with most songs dancing between moods, drum patterns, or melodies and veering off in unforeseen directions. If good kid was Aquemini, To Pimp A Butterfly is Lamar’s Stankonia.

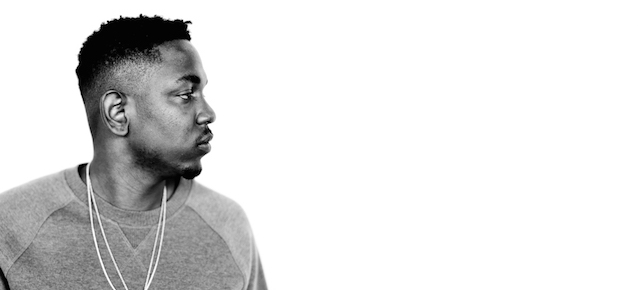

Lyrically, this is by and large the Kendrick Lamar show though; the only other featured rapper to get a full verse is female rapper Rapsody who caps off “Complexion (Zulu Love)” with an endearing celebration of her darker complexion (Snoop Dogg only gets a short half hook/half verse on “Institutionalized”). I’m not sure Lamar needed a supporting cast on this one though, as he remains one of the most talented and verbose rappers around today, which is exemplified throughout the poetically dense Butterfly. His deftly written verses sound deliberate and toiled over while his cadence, flow, and intonation can be quickly altered depending on mood or character. All of this coupled with the clarity and urgency of his Compton forebears in Compton’s Most Wanted and N.W.A. and, like them, a commanding presence that demands to be heard. Like his previous albums, he’s got a lot to say on Butterfly.

Lyrically, this is by and large the Kendrick Lamar show though; the only other featured rapper to get a full verse is female rapper Rapsody who caps off “Complexion (Zulu Love)” with an endearing celebration of her darker complexion (Snoop Dogg only gets a short half hook/half verse on “Institutionalized”). I’m not sure Lamar needed a supporting cast on this one though, as he remains one of the most talented and verbose rappers around today, which is exemplified throughout the poetically dense Butterfly. His deftly written verses sound deliberate and toiled over while his cadence, flow, and intonation can be quickly altered depending on mood or character. All of this coupled with the clarity and urgency of his Compton forebears in Compton’s Most Wanted and N.W.A. and, like them, a commanding presence that demands to be heard. Like his previous albums, he’s got a lot to say on Butterfly.

On paper, this would seemingly amount to a lonely album, and in some ways it is; yet it never comes across as insular or myopic though. Lamar spends a lot of time toiling through his current mindset on Butterfly, unearthing faults and temptations hiding in the dark corners of his mind and confessing them through his lyrics. “I’m trapped inside the ghetto and I ain’t proud to admit it/Institutionalized, I keep runnin’ back for a visit” he utters in the intro to “Institutionalized”. As David Dark keenly described of Butterfly for The Pitch: “A missive of militant transparency, it chronicles afresh Lamar’s tried and true conviction that giving lyrical voice to his deepest fears, anxieties, and resentments is the surest path to shaking free of them.” Similar to Alcoholics Anonymous’ Step 4 inventory list of resentments, Lamar writes explicitly and honestly about his wrongs with hopes of absolution and furthermore, purging them from his psyche. This includes not only the temptations of the Compton neighborhood that he came from, but also the newfound “survivor’s guilt” of his success and the resentment he feels of who he’s become.

Album centerpiece “u”, which acts as a counterpoint to last year’s “Keep Ya Head Up” single “i”, find’s Lamar in the middle of a breakdown in a hotel room, confronting the hypocritical and conflicted man he sees in the mirror as he declares at the onset “Loving you is complicated!”. After a brief interlude mid song where housekeeping knocks on the door to his hotel room, the beat changes and Lamar shows up drunk to the second half, intoning in a drunken cadence regrets over Facetiming a friend in the hospital, a suicidal weakness, and a deep resentment over how his success has affected who he is. It’s one of the most vulnerable songs he’s ever written and reveals that his resentments stem from his own weakness, his own lack of care for those around him. “u” acts as a confession of his darkest demons, a personal dredging of his soul which turns up mostly self-interest at the root. As he told Rolling Stone recently:

“That was one of the hardest songs I had to write. There’s some very dark moments in there. All my insecurities and selfishness and let-downs. That shit is depressing as a motherfucker. But it helps, though. It helps.”

The hopeful and breezy “Alright” follows “u” and Lamar sounds like a weight has been lifted of his shoulders, conveying a sense of absolution after his deep and honest confession in “u”. Lines like “Nigga, I’m at the preacher’s door/My knees gettin’ weak and my gun might blow/But we gon’ be alright” and a simple chorus that repeats the mantra of “We gon’ be alright” portray a hope despite the truth; a self-knowledge of who he truly is and how incapable he is, with a hope placed elsewhere outside of himself. “Alright” is an initial standout as a listener because of this bright, aspirational sense of relief and rises to the surface of the dark soul searching and excavating surrounding it.

As much as Lamar finds fault in himself, in the last quarter of the album he also identifies and calls out the demons around him, most specifically the systemic racism that has plagued American headlines of the past few years. Similar to his personal afflictions, Lamar is compelled to write about his personal experience with this sort of external oppression in hopes of the same truth exposure that can expunge his own demons. Lamar’s experience reflects something larger than himself and on Butterfly, he exemplifies the suffering and conflicted nature of being a young black male in America in 2015.

https://youtu.be/6AhXSoKa8xw

Nowhere is this seen more explicitly than on “The Blacker The Berry”, which Lamar began writing around the time of Trayvon Martin’s death. One of the most personal and dark songs in his catalog, Lamar delivers unblinkingly an emotional performance detailing the oppression and hatred experienced by someone like himself or Trayvon Martin or Mike Brown, simply for the color of their skin. Lamar is incredibly forthright in his delivery–“You hate me don’t you?/You hate my people, your plan is to terminate my culture/You’re fuckin’ evil I want you to recognize that I’m a proud monkey”. You can almost feel him never losing eye contact with you as the listener.

As much as it serves as a timely chronicle of a tumultuous time in America, the song has also become a point of contention for some listeners as well. In the song, Lamar also struggles with a conflicted culpability and capability in himself in the last few lines stating: “So why did I weep when Trayvon Martin was in the street?/When gang banging make me kill a nigga blacker than me?/Hypocrite!”. I understand the concern and I think Lamar does as well, as this sort of notion has been used by some to blame shift or subvert charges of systemic racism, especially in the past year or so. When used in this manner, this sort of blame shifting is harmful and seeks to divert attention away from, in most cases, overwhelming evidence of systemic racism. These sorts of arguments are a common tactic for self-justifying rich young rulers in white middle to upper class America and are rightfully called a spade when deployed in this fashion. Seemingly though, as we’ve seen throughout the rest of To Pimp A Butterfly, Lamar can’t help but confess a similar self-interest he finds in himself that lies at the root of the oppression in the forces outside him—not as a tactic to divert, as many have possibly hinted at, but as an excavating of the same faults with hopes of change.

On To Pimp A Butterfly, Kendrick Lamar frustratingly finds his personal redemption and the redemption of racial relations in America sorely lacking or in media res. Lamar is between the old man and the new man, as demons from his past and present haunt the inner and outer landscape of his present life. From personal experience, Lamar knows that the door for change opens with the kind of soul dredging confession that he exudes in places on Butterfly and he frustratingly sees a lack of honesty, in some ways, in himself. More importantly though, Lamar can’t help but see the same lack of honesty in the sly racism that still courses seductively through a number of powerful and elite institutions in America. As Christ found in his sleeping disciples and Lamar can attest to, “The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak.” Thankfully, in spite of our hiding and dishonesty and shortcomings, He remains faithful, promising to fully redeem and restore each and every self-interested broken system and Kendrick Lamar in due time. Or, as Lamar more succinctly conveys in the intro to “Alright”: “Nazareth, I’m fucked up/Homie you fucked up/But if God got us/Then we gon’ be alright”.

COMMENTS

4 responses to “New Music: Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp A Butterfly”

Leave a Reply

The transition from the second half of “u” into “Alright” is one of the most profound things I’ve heard in music. I was hoping Mockingbird would review this — great write-up.

What an articulate and creative man Lamar is. I appreciate this post here. I have heard a couple of Kendrick’s songs in the past, and have found his lyricism refreshing while equally difficult to stomach. Great job with this piece.