EPISODE 182

It’s not that one’s “dialing back” on insights hard won from the last five years. No, it’s just that you have to be true to the whole of experience. And experience teaches that monism — the “bulk” picture of what we see and face — requires an element of enhancement. That element comes under the heading “dualism”.

It’s not that one’s “dialing back” on insights hard won from the last five years. No, it’s just that you have to be true to the whole of experience. And experience teaches that monism — the “bulk” picture of what we see and face — requires an element of enhancement. That element comes under the heading “dualism”.

Thus when Kerouac, a faithful Catholic, saw through the overly acute dualism of his upbringing in favor of a monism derived from Dwight Goddard, he was making a necessary correction. On the other hand, that correction was not sufficient to break every bondage. Far from it! So at the end of his life, as witnessed by the surprising conclusion to his last novel, “Big Sur” (1962), ‘Jack’ returned to the power of the Cross in relation to the cripplings which life exacts.

In my case, there is something to James Bernard’s music that’s essential.

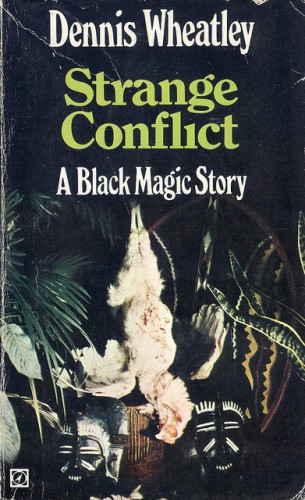

And there’s something to the novels of Dennis Wheatley that’s essential, too.

Who was Dennis Wheatley? He was an English writer of occult (and other) popular novels, who wrote from very much a “Public School” attitude with some strong tilting towards colonialism and certain social attitudes we might now associate with Enoch Powell. But Wheatley’s “attitudes”, whatever you think of them, are not the important thing concerning this remarkable writer. For Dennis Wheatley’s principal theme was satanism and the influence of satan and all his works on human affairs. Wheatley’s books, the most successful of which is entitled “The Devil Rides Out” (1934) and the 1968 movie version of which (below) is one of the best films ever made concerning demonic possession, go to the heart of the darkness of the world. Yet Wheatley also believed absolutely in the triumph of good over evil. I don’t think he was capable of writing a non-happy ending. In almost all his books, the forces of good and of light, and of love, always and absolutely win the upper hand over the forces of darkness and malice.

Moreover, Dennis Wheatley deployed Christian symbols and Christian language massively in his books. (By the way, don’t believe it when you read or when people say that he was a kind of Manichean esotericist. The truth is, Wheatley confessed his faith in Christ specifically and explicitly near the end of his life in the presence of his old friend Cyril “Bobby” Eastaugh, the Bishop of Peterborough; and confirmed his views in two letters he wrote before he died.)

I bid you read Dennis Wheatley. Begin with “The Devil Rides Out”, then move to “The Ka of Gifford Hillary” (1956). Sure, there are tedious “bits” and some long discursus. Just skip ’em. The real focus of this odd inspired writer is entirely superior and important. And hey, maybe it’s true: Maybe the Nazis were in league with satan. Maybe the Stalinists practiced the black arts. Maybe the Hippies …

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sl-FhrtBxQI

By way of footnote, I thought I’d point out some of the remarkable elements that make the conclusion of “The Devil Rides Out” so powerful:

- The breaking of Simon Aron’s spell, around the devilish altar (he moves stage right almost immediately as the mother pronounces her Word).

- The direct enaction of “Talitha Cumi” and the raising of Jairus’ daughter.

- The explicit climax of the epiphanic Cross in the chapel, which is the one thing sufficient to destroy ‘Mocata’.

- The intervention of the mother (which is the inscription from her mother’s (necklace) crucifix: “Only they who love without desire will have power granted them In their darkest hour”).

- The little girl who recites the Hebrew/Latin words that initiate the final divine intervention (in Wheatley’s book, the child suddenly assumes the facial characteristics of Christ, like in Wilde’s “The Selfish Giant”, and addresses the Christopher Lee character and his friends directly).

- The “substitutionary atonement” by which the ingenue ‘Tanith’ rises from the dead because of a life rendered for a life; the attempt of the young supporting hero, Simon Aron, to offer his life for that of the little girl.

- The concluding interpreting words of the Duc de Richleau concerning God and reality, and the end of the evil.

- And finally, the very memorable music of James Bernard, which evokes the “awakening” of the dead Tanith from the deadening spell of Mocata, and then takes the theme of the devil, from the opening credits, and transposes it from the minor key to the major key, adding cathedral bells at the conclusion, to invoke a Christian vision of healing, hope and, in the profoundest sense, victory.

COMMENTS