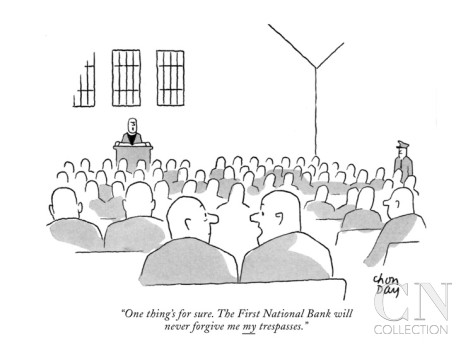

I remember a conversation some years ago where a friend was voicing her chief objection to Christianity. It had nothing to do with science, or politics, or even suffering (at least not explicitly). What she found offensive about the faith was the notion/assertion/accusation that one of our primary needs as human beings is for forgiveness. In her view, the Christian emphasis on forgiveness was part and parcel of a defeatist anthropology that undermined human dignity, perpetuating negative self-understandings that we would be better off without. Furthermore, it set people up as guilty by default, which, when it came to systemic injustice, often disallowed victims from embracing their grievance, thereby contributing to abusive power structures. To admit to needing forgiveness entailed a loss of stature and kept people subordinate, yoked to a pre-ordained morality, or worse.

I remember a conversation some years ago where a friend was voicing her chief objection to Christianity. It had nothing to do with science, or politics, or even suffering (at least not explicitly). What she found offensive about the faith was the notion/assertion/accusation that one of our primary needs as human beings is for forgiveness. In her view, the Christian emphasis on forgiveness was part and parcel of a defeatist anthropology that undermined human dignity, perpetuating negative self-understandings that we would be better off without. Furthermore, it set people up as guilty by default, which, when it came to systemic injustice, often disallowed victims from embracing their grievance, thereby contributing to abusive power structures. To admit to needing forgiveness entailed a loss of stature and kept people subordinate, yoked to a pre-ordained morality, or worse.

That conversation threw me for a loop. Not because her macro concerns weren’t valid (they were/are!), but because of what it meant on a micro level. I had never heard anyone personally deny a desire for forgiveness before. ‘Let’s leave aside the sociopolitical sphere for a second,’ I wanted to ask, ‘you mean to tell me there isn’t anything you feel like you need to be forgiven for?’ I missed my opportunity, but have kept her as an interlocutor lo these many years.

The exchange came to mind the other day while reading Ann Westervelt’s terrific essay on forgiveness for Aeon Magazine, which highlights the increasingly well-researched health benefits of ‘letting go’. She gives us a helpful survey of where things stand in the academic study of forgiveness, focusing more on ‘secular’ understandings of the subject than religious ones:

Forgiveness is a relatively new academic research area, studied in earnest only since Enright began publishing on the subject in the 1980s. The first batch of studies were medical in focus. Forgiveness was widely correlated with a range of physical benefits, including better sleep, lower blood pressure, lower risk of heart disease, even increased life expectancy; really, every benefit you’d expect from reduced stress… Meanwhile, Duke University researchers found a strong correlation between improved immune system function and forgiveness in HIV-positive patients, and between forgiveness and improved mortality rates across the general population…

Of course, all the health benefits in the world aren’t going to make forgiveness any more appealing when the rubber hits the road (or revenge any less bankable). There’s a lot in the rest of the article, though–the discussion of self-forgiveness is worth the price of admission alone. But most of my favorite soundbites come from the mouth of Professor Frederic Luskin, who teaches a ‘forgiveness course’ at Stanford that Westervelt attends. For example:

When I found him, Luskin had been running forgiveness classes at Stanford for about a decade, and had moved away from what he called the ‘big, dramatic’ forms of forgiveness, to which youth and media attention had drawn him early in his career. ‘Even the stuff that forgiveness was supposed to be good for – stuff like murders … it’s so rare,’ he told me. ‘More important is can you forgive your brother-in-law for being annoying? Can you forgive traffic? Those things happen every day. Big things? They happen once in a lifetime, maybe twice. It’s a waste of forgiveness. That’s my perspective. But forgiveness is really important for smoothing over the normal, interpersonal things that rub everyone the wrong way.’

Part of what makes the word – and practice – tough for people, in Luskin’s view, is that it requires a degree of selflessness. ‘For me to say, “Even though you were a shithead, it’s not my problem; it’s your problem, and I’m not going to stay mad at you, because that’s you, not me,” that’s a huge renunciation of self,’ he said. ‘And I don’t know whether it’s our [Western] culture or a human thing, but it’s hard.’

Plus it requires acknowledgement of our fundamental human vulnerability, without getting angry or bitter about it. ‘A lot of times people start with this idea that “I shouldn’t have been harmed”,’ Luskin said. ‘Why not? We live on a planet where harm happens all the time, where children are murdered and horrible things happen; to think that you should escape that is a mammoth overstatement of your own importance and a lack of sensitivity to everyone else on the planet.’

His focus on the mundane as opposed to the dramatic is really refreshing. And I love his inclusion of the annoying brother-in-law; someone who needs to be forgiven for who they are, rather than what they’ve done–it rings truer to life than I would care to admit. And if it sounds like Alcoholics Anonymous, I doubt that’s a coincidence. Lord knows AA understands that an inflated view of oneself can be one of the main obstacles to experiencing real forgiveness, on either end. (Speaking of AA, go JAZ!) The small things are the big things. Plus, the connection between selflessness and forgiveness strikes me as an important one, is it not? Hard not to see the parallel to Christ there.

Interestingly enough, the focus of secular understandings of forgiveness appears to be (has to be?) on how we forgive those who have wronged us, i.e. the giving rather than receiving of pardon (AKA the law of forgiveness, which, as she notes, is an important aspect of most world religions). It’s also worth noting that Westervelt does not ignore the ‘cost’ of forgiveness, whether it be emotional or material or both, nor its fundamentally non-rational nature:

It was a moment I’d read about – this sudden shift when the need to forgive outweighs the drive for revenge. I felt weightless, nauseous, sad, the prospect of letting go of all those years of anger finally opening up a space for grief.

A wise woman once said, as distasteful as certain ‘economic’ models of relating may initially seem, for real forgiveness to occur, there’s got to be “blood on the floor”.

But as beautiful and essential as that process might be, the piece gets into considerably deeper (and more distinctively Christian) waters when it flips the table and deals with the need to be forgiven, something far less subject to our engineering or willpower. That’s also when Westervelt’s own story comes into view. She had shown up to Luskin’s class to observe only, but the subject matter soon triggers something powerful in her:

As a lapsed Catholic myself, [University of Wisconsin professor Robert] Enright’s story resonated with me. Forced to attend church and Catholic school in my youth, I’d rebelled in my teens and twenties, not because I didn’t believe in God but because I didn’t like the self-righteous way in which most of the religious people I knew behaved. I didn’t really miss religion, apart from those moments at the end of Mass where Holy Communion absolved me of my sins and I’d be given a few moments of silence to pray in gratitude. I’d looked forward to those moments – and the peace they brought me – every week. Few other experiences delivered a similar relief from daily worries, and when I read about Enright and his work I wondered if forgiveness might be the thing.

Wow. You have to read the final third of the piece to hear Westervelt relate the locus of her guilt (in her own, remarkable prose), but let it be said that she’s dealing with more than just Garden-variety Catholic guilt. The baggage is real, and if classes like Luskin’s can help people identify, face, and confess their lack of healing–the truth that time does not heal all wounds–then they’re serving a wonderful purpose indeed. Just because the starting point is subjective doesn’t automatically make the forgiveness contrived or false.

Then again, when we detach forgiveness from its religious roots, I wonder if we do so at our own peril. ‘Secular’ understandings of forgiveness, as effective as they may be, can’t help but hit a brick wall eventually, when our need for forgiveness surpasses our capacity to forgive others (or ourselves!)–which it always will. Much as we might wish it weren’t the case, the need invariably outweighs the supply.

Perhaps that’s not the end of the world, though. Because in those moments, be they big or small, when the horizontal limits of forgiveness become painfully real, we may find we have nowhere to turn. Except, of course, to a God who forgives the unforgiving.

Those church doors are red for a reason.

COMMENTS

3 responses to “The Cost and Benefit of Forgiveness (Class)”

Leave a Reply

Tell me more about the ‘red doors’?

Apologies for being obtuse! From what I understand, in Protestant church architecture, doors have often been painted red to symbolize the blood of Christ, that upon entering/exiting the sanctuary you are passing through and receiving the assurance thereof. There are a few other ‘reasons’ behind the convention, but that was the one I was referring to, esp as it relates to the Brene Brown quote about there needing to be ‘blood on the floor’ for real forgiveness to have occurred.

http://www.umc.org/what-we-believe/why-do-so-many-churches-have-red-doors