Several months ago I wrote a post on the well known and now deceased “Painter of Light,” Thomas Kinkade. I addressed Kinkade’s tragic backstory of suffering and how his pain never came through in his I’m-OK-you’re-OK artwork. Most of all I lamented that Christians in particular promote his brand of sentimental artwork because it is safe. What I originally thought would be an obscure post actually got a lot of attention. I was surprised that it struck such a nerve. One redditor called me patronizing: “F*ck Matt Schneider. This piece was condescending and nauseating.”

I don’t usually criticize individual artists and thinkers publically, especially if they’re still living. I’d rather speak generically than pick on someone in particular. But because Kinkade is no longer alive, I feel his work is fair game for targeted critical analysis. Above all though, my heart breaks for Kinkade, who was a fellow Christian and sufferer. His life ended prematurely without recovery.

Perhaps if Kinkade were still alive and perhaps if he had addressed his addictions, he might have moved in new directions artistically, allowing some pain to break into his canvas. We’ll never know, but we can learn a lot by using the body of work he left behind as a conversation piece regardless of his posthumous inability to defend himself. People are allowed to like and defend his pretty pictures all they want. That’s fine with me really, but it also means others of us are likewise allowed to critique the very same paintings.

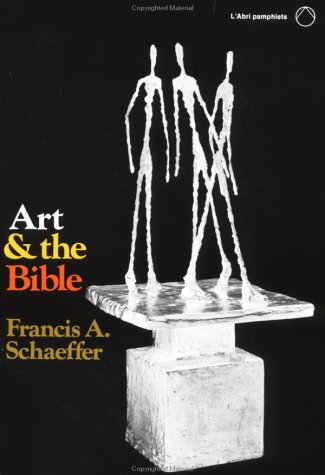

Even if my tone had a hint of snark in my original piece, I stand by the content of what I wrote, and I have some new thoughts. I recently read Francis A. Schaeffer’s Art and the Bible (1973), in which he articulates more effectively what I was trying to say about Kinkade and similar artists. Here are some excerpts from Schaeffer’s book and my connections to the likes of Kinkade:

Even if my tone had a hint of snark in my original piece, I stand by the content of what I wrote, and I have some new thoughts. I recently read Francis A. Schaeffer’s Art and the Bible (1973), in which he articulates more effectively what I was trying to say about Kinkade and similar artists. Here are some excerpts from Schaeffer’s book and my connections to the likes of Kinkade:

The Christian world view can be divided into what I call a major and minor theme. … First, the minor theme is the abnormality of the revolting world. … There is a defeated and sinful side to the Christian’s life. If we are at all honest, we must admit that in this life there is no such thing as totally victorious living. In every one of us there are those things which are sinful and deceiving, while we may see substantial healing, in this life we do not come to perfection.

What Schaeffer describes is parallel to the doctrine that Christians are simultaneously justified and sinful: simul iustus et peccator. Kinkade and similar artists mostly do not (maybe never) expose the minor theme of sinfulness. They instead create a world of total victory without the slightest pain. Schaeffer continues to explain:

The major theme is the opposite of the minor; it is the meaningfulness and purposefulness of life. … So therefore the major theme is an optimism in the area of being; everything is not absurd, there is meaning. But most important, this optimism has a sufficient base. …

God himself has a character and this character is reflected in the moral law of the universe. Thus when a person realizes his inadequacy before God and feels guilty, he has a basis not simply for the feeling but for the reality of guilt. Man’s dilemma is not just that he is finite and God is infinite, but that he is a sinner before a holy God. But then he recognizes that God has given him a solution to this in the life, death and resurrection of Christ. Man is fallen and flawed, but he is redeemable on the basis of Christ’s work. This is beautiful. This is optimism. And this optimism has a sufficient base. …

Notice that the Christian and his art have a place for the minor theme because man is lost and abnormal and the Christian has his own defeatedness. There is not only victory and song in my life. But the Christian and his art don’t end there. He goes on to the major theme because there is an optimistic answer. This is important for the kind of art Christians are to produce. First of all, Christian art needs to recognize the minor theme, the defeated aspect to even the Christian life. If our Christian art only emphasizes the major theme, then it is not fully Christian but simply romantic art. … Older Christians may wonder what is wrong with this art and wonder why their kids are turned off by it, but the answer is simple. It’s romantic. It’s based on the notion that Christianity only has an optimistic note.

According to Schaeffer, Kinkade’s work does not equal fully Christian art (despite his personal faith and large Evangelical fan base). Kinkade’s work equals romantic art. And a helpful side note here is that this sort of false optimism typically doesn’t connect with younger people. But not just young people, also folks who know they are struggling, those who don’t always see the world through rose colored glasses, men and women who at times feel defeated and need their pain addressed before they can have hope. Artists like Kinkade step over the corpses of reality with their eyes averted and nostrils pinched while heading toward escapist sentimentalism. Ironically such fantasies can’t give us hope, only perverted versions of hope, and it’s too bad so many Christians promote this sort of safe family-friendly art.

A scene from “Thomas Kinkade’s Christmas Cottage,” a 2008 direct-to-video biopic, starring Jared Padalecki as Kinkade, seen here walking past one of his own paintings.

But let’s not ignore the flipside to the equation. What about artists who dwell only on the minor themes? Isn’t that nihilistic? Isn’t cynicism equally dishonest? Schaeffer anticipates these questions:

It is possible for a Christian to so major on the minor theme, emphasizing the lostness of man and the abnormality of the universe, that he is equally unbiblical. There may be exceptions where a Christian artist feels it his calling only to picture the negative, but in general for the Christian, the major theme is to be dominant—though it must exist in relationship to the minor.

In other words, good news ought to be the final word. While brokenness and guilt are equated with minor themes, the gospel most closely parallels the major. We need both to proclaim hope—joy beyond the sorrow. Joy is privileged, but it can’t stand alone. This is something Kinkade unfortunately never seemed to understand because his opinion of humanity and the world (at least the one on display for the world to see) was too enthusiastic to ring true with ordinary sufferers:

There are, of course, some works of modern art which are optimistic. But the basis for that optimism is insufficient and, like Christian art which does not adequately emphasize the minor theme, it tends to be pure romanticism. These artists’ work appears dishonest in the face of contemporary facts. …

There is a parallel in our conversation with men. We must present both the law and the gospel; we ought not end with only the judgment of the law. Even though we may spend most of our time on the judgment of the law, love dictates that at some point we get to the gospel. And it seems to me that in the total body of his work the artist somewhere should have a sufficient place for the major theme.

Schaeffer does a much better job explaining what I was attempting to explore with Kinkade’s art and life. Art that rings true—art that Christians ought to embrace—needs to in some way address both the minor and major themes of life. Perhaps this point isn’t imperative for a single piece of artwork, but in an artist’s full body of work over a lifetime, to have one theme without the other is either nihilism or sentimentalism. We shouldn’t applaud sentimental artists for safe aesthetics offering escapist fantasies. Truth and hope lie in light overcoming darkness, not ignoring it.

Featured image: “Firelight Cottage” by Nathan Stillie.

COMMENTS

17 responses to “Francis Schaeffer on the Problem with Thomas Kinkade’s Optimistic Art”

Leave a Reply

Pastor,

Fine points all, but I think quoting Francis Schaeffer is to bring to the table the whole plethora of 1970s/80s/90s phenomena he left in his wake (shorthandedly, “Christian Right”) that not only wrecked havoc upon American religion (bringing us to the point where ministries like Mbird are tragically needed to reform evangelicalism), but did little in the end to revive the “thin tradition” (Douglas John Hall) of justification. Calvinists are, as you know, not of one mind concerning his legacy– the transformationalist wing sees Schaeffer as a patron saint, while old-liners in, say, the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, see him as an opportunist no different from a Jerry Falwell or Pat Robertson, exploiting cultural discontent to promote what they see as heretical deviation from monergism. My point: I think a less ideological, more knowledgeable author would have been a better choice for you to quote than Schaeffer, even he or she is a name readers do not immediately recognize. Just a suggestion.

Thanks for a very interesting post, Matt. I like Schaeffer’s distinction between the major and the minor themes, but I’m a little uncomfortable with his judging an artist’s output as Biblical or not by the ratio of the one to the other. In art, as in life that sounds like a little something called “Law.” Granted, he does allow for exceptions.

Also, in light of Mike’s comments, just a word in Schaeffer’s defense. I’m not qualified to judge his legacy, but if (according to some people) he merits comparison with Robertson and Falwell, where was his empire? I know people who studied with him, people who worked alongside him, and people who knew him as a friend. It’s true that, late in his life, Franky led him into alliance with some unfortunate characters, but by all accounts the man himself was humble, sincere, and deeply compassionate. I spent a summer at one of the L’Abri branches, where people in many stages of faith and unbelief lived and studied, at nominal cost. All were welcome, and all were accepted. I don’t know how much of a monergist he was, but that was the love of Christ in action.

Ken, it is more than “a little something called law” that Schaeffer employs. I supposed it never occurred to you that his public humility and persona might amount to little more than a flouting of Matthew 6:1, where Jesus explicitly told His disciples to forego any possibility of mixing ego with the gospel. As I see things, you were seduced. At base, “the glory of God” was Schaffer’s goal, taken to inhumane extremes by hard Calvinists from Beza onward. Admittedly, you were an impressionable youth and could be forgiven at the time for your enthusiasm for a guru-like cult figure who was frankly of a piece culturally with the 1970s fixation on charismatic personalities. But that legacy has borne bitter fruit in our time, and I imagine the Rev. Mr. Schneider would agree with me. And even were he the saintly figure he is made out to be by his acolytes, it still would not qualify him per se as an art critic. By those standards, I fully indict some of my fellow progressives also, namely the Crossans, the Borgs, and the Ehrmans for exploring the same celebrity consciousness that is keeping Americans in bondage. The very intensity of his son’s estrangement, whether you agree with it or not, is evidence that his closed worldview poses serious personal costs, none of which are in my sights mandated by, or compatible with, true Christian discipleship.

I really appreciated this post, Matt. It was helpful.

Thanks, Mike, Ken, and Brandon. I recommend reading my original piece (linked above), which gives at hat tip to Dan Siedell, someone I trust more than Scaheffer on the topic of art. Of course, no blog post can be the definitive word on anything–thank God! True: there are probably a gazillion other people I could cite besides Schaeffer, but on this one point about minor and major themes, I have to agree with him. Regardless of what anyone might think of Schaeffer the man and other things he’s written, here he shines a helpful light on the so-called “Painter of Light” and those like him. That’s all.

Schaeffer is a perfect example of how one can be lionized by fellow Christians at one point in time, only to be unmercifully trashed a few years later. You would think the poor man was some kind of ignorant devil incarnate spiritual leper. I found him to be an extremely kind person who really hurt over the brokenness of the world and who suffered greatly in his final years. Not perfect, but not to blame for everything that hacks me off about the so-called “Christian Right” either. I’m greatly encouraged to see his work used here, and it needs no apology.

Mr. Cooper, Schaeffer deserves his infamy for “unmercifully trashing” anyone not in agreement with his obsessions with apologetics and his totalitarian hermeneutics that intensified the basic Puritanism of American evangelicalism (he came up through the Bible Presbyterian Church, a break-off of the OPC emphasizing total abstinence from liquor and separatism as a first principle of faith, regardless of their concurrence with the Westminster Confession).

I do not care about how well he treated his inner circle; what that has do with his legacy is not important. His son Frank, in his memoirs, characterized him as a wife-beater, while the acolytes circle the wagons.

The mentality of one who thinks he is in possession of God’s omniscience cannot permit freedom or dissent; hence he had no problem in “disciplining” his beloved Edith. If Schaeffer were living now, I guarantee you he would not approve of Mbird; we are much too Lutheran for his taste, in basing our foundation faith in the crucified and risen Christ rather than (a fallen conception of) Divine omnipotence and glory.

Sure, he did not work alone to mobilize religious conservatives in the 1970s, else he would have been dismissed as a freak like a Carl McIntire or a Bob Jones were in the generation before him. But his patina of intellectualism and the cultural dislocations and anxiety of the time that he exploited make him doubly damnable. I am sorry to see that you have been taken in by his cultus.

Let me put it this way: I can make a claim to be “really hurt over the brokenness of the world” as Schaeffer was, but I am not in the slightest interested in controlling the beliefs of others as he was. It is clear in the Gospel that such is a work that achieves ABSOLUTELY NOTHING for the salvation of the doer, let alone the recipient of the “gift.” Our anger does not produce God’s righteousness (James 1:20); Schaeffer was an angry, angry man. Fundamentalism is inseparable from anger and moral disgust and would die without those elements, all the rhetorical hot air of Reformed scholastics notwithstanding. So, yes, I am quite prepared to characterize Schaeffer as a “devil incarnate spiritual leper.” You see, he was a Sadducee. Jesus pronounced doom upon them and the Pharisees at every point, and we will get that condemnation ourselves if we follow the lead of false prophets like him.

Matt, I found both of your pieces to be fair and necessary critiques of Kinkade’s art. I would add that a major problem, perhaps the major problem, with Kinkades’ art is that its prettiness and shallow sentimentality—that consistently ignore the sorrows and pains and even the larger joys of real life—simply reconfirm our shallow emotions and act as a block toward a deeper appreciation of the artistic expression of what life is, and who we are. Great art—even really good art—has the capacity to enlarge our experience, even our souls, in a way that shallow art or mere entertainment cannot. What is also sad is that, based on some of his earlier works, Kinkade had considerable talent and some depth of vision. What stopped him short in his artistic development and led him to constantly reiterate visual and emotive clichés, I do not know.

I really like your analysis from Schaeffer. I guess I never considered Kinkade’s paintings to have this kind of influence. And maybe I’m clueless about Kinkade’s own view of his paintings. But I see them mostly as attractive (quite innocently) to the shopper in Hobby Lobby who likes the scene of glowing cottage in a winter woods.

Other Matt, I can see where you’re coming from. To a certain extent, Kinkade’s work isn’t worth much attention. The thing that I am trying to tease apart really is the Christian embrace of vapid art as safe and family friendly (e.g., footprints in the sand). I have more to say about this with respect to music–probably another post is in order on that subject. And Mike, I’m not sure anyone, from a Christian perspective, deserves an unmerciful trashing. Lord have mercy on the Schaeffers and Kinkades among us, which is why I’m trying to be evenhanded in my critique. The thing I’m learning from these two posts is that Kinkade seems to be a bit of a lightening rod, and here I’m seeing Schaeffer is too. For this reason, I will probably have more to say about Kinkade in the future … the book isn’t closed and probably never should be. I’m glad what I hoped to be a conversation piece has, in fact, stimulated conversation.

I look forward to your next post on this subject, Matt. And speaking of Schaeffer and the arts, sculptor Mark Potter just gave three art-related lectures at Massachusetts L’Abri. They’ll be available for streaming, sooner or later, on their lecture schedule page.

I wondered why I never saw the “following” of Kinkade. It never pulled me in. I also could never stare at spots and see a picture. I was in college when Schaeffer was at his height and everyone was reading him. I think 35 years later, I need to read him again.

What if kinkade painted what he wanted that had nothing to do with Christianity?! I am a Christian who does struggle and suffer quite a bit but I am also a romantic, a dreamer and love to escape in my head. I love his paintings and I don’t call them Christian or non-Christian, they’re just beautiful and hopeful and make me want to have a cottage built for myself! Maybe he was simply painting what he wished his life could be like considering his addictions. I am analytical myself but his paintings are just simply to enjoy!

I agree with Betty’s perspective above (posted 6/28/17). When I gaze at his paintings, it inspires hope in the coming Kingdom. Maybe we got it wrong! Perhaps he wasn’t ignoring the ‘minor theme’ so prevalent in the Scriptures and in our current reality as he was pointing us to the day when God’s Kingdom comes in its fullness and His will is finally done on earth as it is in heaven. After all, we get the restored earth back; the renewal of all things! I’m constantly reminded of the brokenness and suffering we’re all experiencing in this present age and deeply appreciate anything that God brings to me that is a reminder of the Redemption that is coming!

I am not a biblical scholar, an authority on Christianity, nor a particularly good writer, so I won’t attempt to comment on those subjects. But I would like to offer a simple observation. I can’t help but see Amy Winehouse as the polar opposite of Thomas Kinkade. Her art was as infused with her pain as Kinkade’s art was lacking in any smidgeon of his. Her songs were an unabashed cry for help battling her addiction demons. But, alas, the end result was sadly indentical. Their demons overpowered them and took them from us far too soon.

Nope, you’re still a moron. Who has the authority to decide art also needs pain? When my life is crap, I don’t need to hear over and over again how crap life is. You also want torture devices in Disneyland? Do I need to vomit every time I eat a delicious cake? Conclusion: you’re a moron.

P.S. Kinkade is not at all my style, but you are still a moron.

The only problem with Kincade’s art is that people think he needed to follow their preferences and desires instead of his own. It was HIS ART, and obviously people liked it and appreciated it, which is why it was so widely popular. Do you have furniture or decor in your house that you bought because you like the way it looks and feels? Or do you stick a tack under your butt so you can be reminded that life is painful and not comfortable? People just have to be judgmental, which I am sure contributed to his addiction and end of life. He was talented, his paintings were beautiful, and if someone didn’t think so, then don’t buy them! Beautiful things exist. God’s creation is covered in beautiful things. Am I ignoring Christianity by taking a picture of a gorgeous sunset because it doesn’t represent pain? Absolutely not! I get enough pain from other means, and obviously Thomas had plenty of his own. He didn’t want to express that pain in his art, he made something beautiful and relaxing. Maybe he was redirecting his pain to focus on the good that is to come. Good for him! That doesn’t make him wrong; his art is his own creation and no one has any right to say what he should or should not have painted I doubt God scolded him when he reached heaven and said, I don’t appreciate you making such peaceful images! Where was the darkness!? If you want pain and suffering on your walls, then no one is stopping you from buying that instead. No human is fooled into thinking we live in Eden because they appreciate some pretty paintings. Focus on the plank in your own eye, and appreciate a talented painter who painted what he wanted, and many people appreciated.