1. Whatever form the Law takes, dictated by fickle zeitgeist, it leaves behind a few years later. Forms can be remarkably inconsistent among different demographics, and after we finally escape one form of (little-l) law, we look back and scorn it, wondering how we (or anyone else) ever could’ve gotten so attached to it. For example, masculinity: the more and more we escape the pressure for men to be super macho, the more contemptible we find its earnest expression, as if embarrassed by our previous adherence. Even commercials which target the lowest common denominator of the masculine – such as Axe – must make a pretense of irony or self-awareness during their commercials, just so we’re all in on the joke (DFW’s “e unibus pluram” treats this brilliantly). Because it’s insulting to have that you’ll-be-manly-with-our-deodorant BS sold to me: I have as much contempt for meathead Rob Lowe as anyone else – and I’ve never really cared about that stuff anyway.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p-7OsUzUT9w

To linger on the gender stuff for a second, a great New Yorker article a while back focused on a women-only music festival, which, when transgender women wanted entrance and were refused (on the grounds that if you’re born with male privilege, you can’t get rid of it so easily) , suddenly went from cutting-edge pioneer to cultural villain. You can find yourself afoul of the latest moral revelation at any moment.

Speaking of which, Style.com had a nice bit on how braggy fitness can be. No surprise, probably, but there it is. Quote of the article comes from ‘Ana’, mild language, ht CB:

It’s like the only acceptable lifestyle brag,” says Ana, 26, a Manhattan spinning enthusiast. “You are a douche if you brag about your car or how much money you make, but bragging about how much you spin is normal, though still very annoying.

I’d love to meet the people who think it ‘douchey’ to talk about their cars but somehow restrained, normal, and non-self-aggrandizing to talk about spinning, whatever that may be. The author continues:

There are other factors as well. With income inequality at an all-time high and obesity rates continuing to spike among lower-income

individuals—even as this wellness culture flourishes—eating right can give the privileged class a sense of moral superiority. Not that shopping at Whole Foods and going to spin classes make you morally superior, but they won’t likely make you look or feel bad in the company of the less fortunate. “When you spend big bucks on experiences that supposedly are good for you, there seems to be less guilt than when it is just a physical luxury item,” explains Compeau. “Spending $10,000 on a handbag might prompt significantly more awareness of the purchase and consumption being more ostentatious than if the same amount was spent on an exclusive gym membership or exercise classes.”

New boss, same as the old. You wonder what things’ll be like in 20, 30 years, when talking about exercise is more widely considered “showy”, when people feel the need to be sheepish about their Nepalese sea salt, and so on. People continue to indulge in pseudo-moralities, and these moral hobbies are, as ever, not cheap.

A final thing – if the expensive handbag is a proxy for class/wealth, and thus serves as a brag-piece, I wonder what SoulCycle is a proxy for. Maybe the same thing,but there’s also an element of stress-bragging there, a la Kreider, and probably some sort of body/youth fixation going on. Anyway, turns out self-justification is inescapable: once the old forms are finally seen for the farces they always were, we invent the new ones and take them with the utmost seriousness.

2. At the Huffington Post, Johann Hari previews his new book on the War on Drugs, Chasing the Scream. The terms of the article seem a little very overwrought/sensationalistic, but there’s some interesting stuff there. Turns out that while chemical hooks play a role in addiction, environmental factors, especially isolation, perhaps play bigger ones, ht AL:

[Portugal, with a terrible drug problem, decriminalized and put the enforcement savings into rehabilitation programs.] The results of all this are now in. An independent study by the British Journal of Criminology found that since total decriminalization, addiction has fallen, and injecting drug use is down by 50 percent. I’ll repeat that: injecting drug use is down by 50 percent. Decriminalization has been such a manifest success [HuffPo: maybe] that very few people in Portugal want to go back to the old system. The main campaigner against the decriminalization back in 2000 was Joao Figueira, the country’s top drug cop. He offered all the dire warnings that we would expect from the Daily Mail or Fox News. But when we sat together in Lisbon, he told me that everything he predicted had not come to pass — and he now hopes the whole world will follow Portugal’s example.

The shift from material causes – fix the problem by making it impossible – to more supportive, emotionally-discerning solutions is a welcome one (though a little too given to engineering, in the way that might make someone feel wrongly guilty for a loved one’s problem). He continues:

Loving an addict is really hard. When I looked at the addicts I love, it was always tempting to follow the tough love advice doled out by reality shows like Intervention — tell the addict to shape up, or cut them off. Their message is that an addict who won’t stop should be shunned… But in fact, I learned, that will only deepen their addiction — and you may lose them altogether. I came home determined to tie the addicts in my life closer to me than ever — to let them know I love them unconditionally, whether they stop, or whether they can’t.

On a related note, the Economist this week noted a stat from a 2011 study about prisons: just one in-person visit “can reduce the likelihood of an inmate reoffending by 13%”. Connection/love does seem to help.

3. In culture, the recent publication of the David Foster Wallace reader allows an opportunity to reflect on his work. Newsweek ran a thoughtful tribute pointing out a few of the reasons why Wallace was such a fresh, distinct writer:

One of the essays included in the Reader is “Authority and American Usage,” nominally a review of Bryan A. Garner’s A Dictionary of Modern American Usage. Which it is, precisely in the way that Moby-Dick is about whales. Wallace starts by describing his upbringing as a SNOOT, which may mean, according to Wallace, “Syntax Nudniks of Our Times” or “Sprachgefühl Necessitates Our Ongoing Tendance,” the latter preferable in the Wallace household to the former:

‘I submit that we SNOOTS are just about the last remaining kind of truly elitist nerd. There are, granted, plenty of nerd-species in today’s America, and some of these are elitist within their own nerdy purview (e.g., the skinny, carbuncular, semi-autistic Computer Nerd moves instantly up the totem pole of status when your screen freezes and now you need his help, and the bland condescension with which he performs the two occult keystrokes that unfreeze your screen is both elitist and situationally valid). But the SNOOT’s purview is interhuman life itself…you can’t escape language: language is everything and everywhere, it’s what lets us have anything to do with one another; it’s what separates us from the animals; Genesis 11:7-10 and so on.’

An essayist today, assigned the Garner review, would probably pound out a dreary think piece about why bad grammar is good for American democracy. Or maybe she would cite a legion of statistics (“one study found that…”) to bolster the opposite case. Maybe he would write a deeply personal, utterly banal piece about having a grammarian mother, his conclusions thoroughly pedestrian and unoriginal (“So whenever I see the predicate nominative, I always remember…”). I can’t think of anyone but Wallace who could bring so much insight and personal reflection and curiosity and, best of all, joy to the question of whether split infinitives matter.

Indeed, the originality and authenticity of Wallace (and it’s no coincidence he’d be the first to question/shy from those labels is sorely missed, predictably counterintuitive and generically original thinkpieces notwithstanding. But this joy seems almost forbidden as the sign of the overenthusiastic amateur (literally love-er), someone without the requisite disillusionment and, more so, self-consciousness, which is usually taken for perspective. It’s writing that’s risky, vulnerable, and astonishingly perceptive. George Eliot once wrote that “If we had a keen vision and feeling of all ordinary human life, it would be like hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat, and we should die of that roar which lies on the other side of silence.” While many writers are busy focusing on a field of interest to block out the din or, worse, snobbishly pretending they’ve heard louder, Wallace somehow simply beholds this overwhelming stream of perception and wrestles it into form, while never quite losing that childish delight and awe to irony for its own sake.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6MbJi0xtnEA

4. Vox media features the bizarre video above, a simultaneous playing of all Friends season 1 episodes superimposed on one another. Comparing these things for lots of 90s shows, or TV shows in particular, would be interesting, a possible window into each show’s feeling and sensibility. But for now, just Vox’s commentary on 90s TV ‘meta-analysis’:

What’s striking about the video is how carnivalesque everything appears. Once you hit play, you’re bombarded with an avalanche of blurry images scored to the sounds of comical dialogue and laughter. If you keep watching, there will come a point where you realize just how formulaic the show was.

And it makes those audience-laughs, which cue the viewer into “yeah, this is funny, now’s the time to laugh” seem creepier than they were.

5. In anthropology, Heather Havrilesky chides a moralistic person who’s confessed to feelings of resentment and judgment from always having the right moral compass, while others don’t. The whole thing’s worth a read, but Heather writes back with a strong dose of compassion:

…Most people don’t feel loved enough. Most people feel abandoned and lost. Most people are trying, with every word out of their mouths, to get more love — MORE MORE MORE — from the people around them. Most people chase money, real estate, stuff, fame, attention, sexual intrigue, gossip, just for a little taste of love, just for a momentary glow of acceptance and happiness from the world.

You need to know that bad people will suffer? They’re already suffering! Meanwhile, who are YOU to say who’s bad and who’s good? Look in the mirror. You feel disappointed in yourself. You want more. You want what other people have. You want more freedom. You aren’t giving yourself an inch. You aren’t allowed to fail, to be flawed, to be soft, to be fallible, so you’re taking your anger at yourself out on everyone else.

I get it! I’ve been there. You’re intellectualizing your feelings, whipping yourself into a lather of rage and judgment, instead of admitting that you feel rejected and sad. You’re not vulnerable with your friends, so they’re not honest and vulnerable with you. As a result, you don’t understand what they’re going through.

Your ex has moved on, but you haven’t, and it makes you furious. You think you have to be RIGHT in order to set things right. But that’s not true. You actually have to be WRONG. Admitting that you’re wrong will release you from this purgatory.

Your way of doing things is not the only right way. Walk outside and look at the people you see. Do you think they aren’t in pain? Do you think they aren’t lonely? Not everyone can lift their heads above what’s immediately in front of them. Not everyone has the hope onboard to fuel new excursions into the unknown like you do. Some people are just clinging to whatever is within reach.

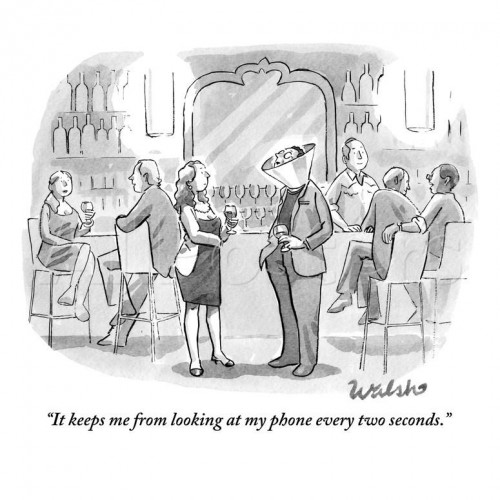

6. In tech, Smithsonian.com reports a study of our dependence on cell phones, ht SZ:

During the study, participants were placed in a cubicle and asked to perform word search puzzles. Researchers monitored their anxiety levels, heart rate, and blood pressure while the subjects had their iPhones with them.

Then, the real experiment began. Researchers told participants that their iPhones were causing interference with the blood pressure cuff and asked them to move their phones. The phones were placed in a nearby cubicle close enough to be within eyeshot and earshot of each subject.

Next, the researchers called the subjects’ phones—now placed out of reach—while they were working on the puzzle. Immediately afterwards, they collected the same data.

The results changed dramatically. Not only did the participants’ puzzle performance decline significantly while the phones were off-limits, but their anxiety levels, blood pressure and heart rates skyrocketed.

The study was used as evidence that students and workers might perform better with greater cell phone liberties, because they’ve become almost an extension of ourselves. And while I wouldn’t disagree with that, it reinforces suspicions of growing dependence. Over a half-century ago, Hannah Arendt wrote that “If it should turn out to be true that knowledge (in the modern sense of know-how) and thought have parted company for good, then we would indeed become the helpless slaves, not so much of our machines as of our know-how, thoughtless creatures at the mercy of every gadget which is technically possible…”

It’s that last part of the Arendt quote which seems to apply here: amidst the banality of our thoughts or lack of thought – even the banality of our concentration on a problem – we’re desperate for tech to somehow short-circuit things or to speak to us, to give us something new. Hence the phone calls being so exciting: what great piece of news, what great opportunity or point of connection or conversation were they missing out on? It’s perhaps not so much that phones are an extension of ourselves, though they are to a degree, but more than they’re the locus of our sense of something better, something to relieve our sense of boredom or the mundane.

7. Checking in with Pope Francis I, the politics still loom large, with progressives as naively triumphalistic as ever and conservatives still as shrilly alarmist as ever (though Maureen Mullarkey’s FT article has an absurdity sui generis) Which makes it refreshing when Ross Douthat and James Martin, S.J., have an at-length, fantastic discussion on the politics of Francis, ht SZ:

[JM, SJ:] First, do you worry that we might be so enamored of tradition (not Tradition but simply tradition) that we may miss what the Holy Spirit is asking of us, and unable to read the “signs of the times,” as Christ asks? More to the point, do you worry that our church could unintentionally repeat what Jesus accused some of the Pharisees of doing, that is, laying down “heavy burdens” on people, seemingly more concerned with laws than human beings?

Let me be clear: I’m not calling either you, or anyone who agrees with you, or anyone else for that matter, a “Pharisee.” But Jesus invites us to ask ourselves if we are behaving in that manner. Thus, the church—that is, we, the entire People of God—must always be alert to the danger of relying on the law so much that we miss Christ’s call for mercy. Again, it is always balance: law and mercy. But in my mind Jesus tips the scales consistently to mercy, as when he levels his own judgment on the Pharisees, “They tie up heavy burdens, hard to bear, and lay them on the shoulders of others; but they themselves are unwilling to lift a finger to move them.”

As I say, it’s a balance, but ceteris paribus, stinginess with mercy seems like something that we would have to answer for when we finally meet Jesus Christ….

[RD:] What it has more in common with [than stereotypical Pharisaism, and I speak from experience, is certain forms of Mainline Protestantism and megachurch evangelicalism: Notwithstanding what still emanates from the Vatican, we’ve become a church of long communion and short confession lines (and you’re more likely to find me in the first than the second), of Jesus-affirms-you sermons and songs, of marriage preparation retreats (like mine) where most of the couples are cohabitating and nobody particularly cares, and of widespread popular attitudes toward the divine and toward church teaching that mostly resemble H. Richard Niebuhr’s vision of a God without wrath, men without sin, and a Kingdom without judgment.

Bonus: Win Bassett interviewing Christian Wiman (not included above because there’s too much goodness to choose from), Maslow’s Nicholas Carr’s hierarchy of innovation (improving self-actualization!), the week’s worst music video (in terms of sonic quality), Jackie Chan and John Cusack’s coming late-antiquity East-meets-West epic (Dragon Blade, below), and a BBC adaptation of Hilary Mantel’s masterful Wolf Hall (English Reformation novel), two below. Also, the release party for DZ’s A Mess of Help is happening in New York tomorrow at 7, St. George’s Church – hope to see some folks there.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply