Over the summer, my father gave me an old, Smith & Wesson Model 10 .38 revolver. His father, who received it as a gift from his best friend, gave it to him. Family lore has it that my grandfather’s friend took it from someone else in an apparent altercation. What makes this interesting is the revolver itself and the historical context in which it existed. On the wooden handle, there are five notches… four parallel notches with a fifth crossing them out. Now, that could mean anything… squirrels, rats… but the heyday of this revolver came in the mid-20th Century in a place called Lowndesboro, Alabama. Lowndesboro is situated almost exactly between Selma and Montgomery. As I hold the revolver my father gave to me, the thought of what those notches could mean is chilling.

Over the summer, my father gave me an old, Smith & Wesson Model 10 .38 revolver. His father, who received it as a gift from his best friend, gave it to him. Family lore has it that my grandfather’s friend took it from someone else in an apparent altercation. What makes this interesting is the revolver itself and the historical context in which it existed. On the wooden handle, there are five notches… four parallel notches with a fifth crossing them out. Now, that could mean anything… squirrels, rats… but the heyday of this revolver came in the mid-20th Century in a place called Lowndesboro, Alabama. Lowndesboro is situated almost exactly between Selma and Montgomery. As I hold the revolver my father gave to me, the thought of what those notches could mean is chilling.

Lowndes County had a history quite similar to that of Selma in the mid-20th Century, although less publicized. Viola Liuzzo, a participant in the Selma-to-Montgomery march, was shot dead by Klansmen just outside of Lowndesboro in 1965. As a child visiting my grandparents, I heard incredible stories about the violence of Sheriff Otto Moorer, Lowndes County’s sheriff in the 1940’s and 1950’s, and one of the more powerful citizens of the County at that time. My grandmother and aunt actually watched the Selma-to-Montgomery march go right through Lowndesboro, even though my grandfather forbade it. This contrasted so greatly with the incredible love I felt in Lowndesboro… fishing, hunting, swimming, shooting, fish fries, Thanksgiving, and ties around too-tight collars in Sunday School at the Methodist church.

The revolver with five notches tells me that the place I always idealized as a child, a place of great love, support, and nurturing from my grandparents, had a very sinister and shadowy side. Looming not far from stringers of catfish and the community swimming pool were unmarked graves of those who died violent deaths and unnamed specters that were situated uncomfortably beneath the consciousness of everyone there.

As I viewed the trailer for the upcoming movie “Selma”, my mind went back to my childhood and the revolver with five notches. It is surreal to see all the notable actors and hear the soundtrack while footage of a town I know so well rolls across the screen. The music especially is so foreign to the aura of the place. I was raised in Birmingham (which had its own problems) but the images I saw still brought great pain. I can only imagine what it will be like for someone who lived through that era and was fully cognizant of what was going on.

It is good not to forget what people are capable of. It reminds us that human depravity cuts across ideological lines, warping abstract ideas into something that can barely be recognized. Is it any wonder that African-Americans hold decentralized power in just as much suspicion as Eastern Europeans do centralized power? How informative it is that the height of violence against African-Americans in the South was happening concurrently with the Stalinist purges in the old USSR.

But those are just ideas. Abstractions. Decentralization… returning power to localities. Centralization… homogenizing and enforcing justice.

The notches, though, those are real. They represent (or could represent) real people with real names and real families. Perhaps they had a child much like yours. Perhaps they were criminals. Maybe they had great hope in the movement in their midst. Or maybe they resigned themselves to a life in the fields or the home of some white family. Maybe even my family. Perhaps they were bootleggers and had nothing to do with Selma, Dr. King, and the Klan. Then again, maybe the notches represent not humans but squirrels.

Regardless, each notch reminds me of a real human life affected by real human depravity and real human tragedy. Imagine holding your newborn son in your hands… the joy that brings… and then remembering the world that you have brought that boy into. Imagine it is Selma around 1950 and you are an African-American woman.

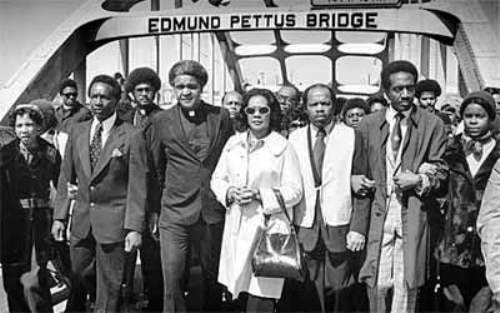

These days, Selma typically gets international attention every four or eight years, depending on who is running for president. They will come at the anniversary of the tragedy at the Edmund Pettus Bridge and make a big show. It is a worthy remembrance, one which also happens to serve their purposes. Why not? And yet, I wonder if this attention every four or eight years, along with the new movie, is helpful. The question that always comes to my mind is: Has Selma ever been allowed to heal? Has Selma ever been given the space to contemplate, repent, pray, and forgive?

Selma is such an abstract idea… such an “issue”. Real people live there, though. 1965 really is the recent past. The memory is so present. You can feel it when you are there. Can something heal if the scab is continually being ripped off? Is it being ripped off for the right reasons?

Justice is such a seductive word. The people of Germany can testify to that. From Fawltey Towers to the continuous stream of books and movies about the horrors of the Third Reich, what German isn’t painfully aware of his or her heritage? What white Southerner isn’t aware of his or her heritage and felt the sting of derision? Certainly, some have fallen into defensiveness as is wont to happen. Confederate flags on trucks and fraternity houses. Isn’t that just an idea and abstraction, too? Perhaps they need a revolver with five notches, too. Others flee to different parts of the country or world and work to remove any trace of that sort of provincialism. They attempt to remove themselves from the position of judged and place themselves in the position of judge over the very people they left. Justice creates such strange behavior. Does a continuous date with justice help?

What about being left alone? What about being given the time to look back and look at ourselves and look at our neighbor across the tracks. I’m not talking about moving on. ‘Moving on’ may be one of the most useless sentiments in human history. I’m talking about forgiveness. Forgiveness can be so politically useless. It takes away fear of the other. It takes away resentment. It takes away defensiveness and enables real sorrow and repentance. It removes levers in the soul by which people can mobilize and manipulate. It fashions people into equals, all with their own burden to bear. Perhaps it even enables someone to help another with a particularly heavy burden. It might even cause some measure of sobbing and improper spectacle.

Has forgiveness come to Selma? I don’t know. It’s been so long since I’ve been there. But are all these trips back to 1965 helping? This protracted walk with justice? Again, I don’t know. I do know that we should never forget. I also know how cynical people can be, myself included.

But what I know for sure is that I have this revolver with five notches, and I don’t know what those notches mean. I look at them, and I feel how impossible forgiveness must be. If those notches are what I fear they are, there is a family behind every one. Mothers, fathers, wives, husbands, sons, and daughters. Cousins and friends. Perhaps fiancées who ask every day “What could have been?”. If they are what I fear, there is a life behind each notch. What gives life to the lifeless? It is not an easy question.

COMMENTS

8 responses to “Reflections on a Notched Gun from Selma”

Leave a Reply

Loved this. What a crazy cultural artifact and reminder of how bad things can get. I hope forgiveness one day comes to Selma. Come Lord Jesus!

Wow. David Browder, thank you for this! It is a hard thing to grasp, the depths forgiveness must travel.

What a piece, DB!

Wonderful insights, David. I have quite a few friends in Selma myself. Every time I go there I feel as if I’m haunted by two ghosts: civil war and civil rights, neither of which have healed. What an odd place. But I love the people there.

I am told my grandad was first cousin to Otto Moorer which my grandad is black this was very uncommon back in those days. My dad said Otto was extremely brutal towards blacks and that young black girls would run and hide in ditches when they saw his patrol car coming to avoid being raped!

Hi

I’m actually in a research project about this individual. If you could please contact me.

Otis L. Moorer,

I am extremely interested in speaking with you.

My grandmother was Otto Moorer’s half sister.

She was black.

You can contact me at otis.moorer@gmail.com

303 653 2986 my grandad was Tommie Moorer