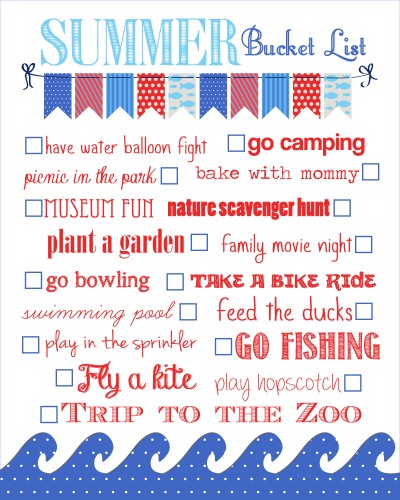

1. The New Yorker weighs in on “bucket lists“, ht DH:

Whence the appeal of the bucket list? To stop and think about the things one hopes to do, the person one hopes to be, is a useful and worthwhile exercise; to do so with a consciousness of one’s own unpredictable mortality can be a sobering reckoning, as theologians and philosophers recognized long before Workman Publishing got in on the act…

As popularly conceived, however, the bucket list is far from being a reckoning with the weight of love in extremis, or an ethical or moral accounting. More often, it partakes of a commodification of cultural experience, in which every expedition made, and every artwork encountered, is reduced to an item on a checklist to be got through, rather than being worthy of repeated or extended engagement. Dropping by Stonehenge for ten minutes and then announcing you’ve crossed it off your bucket list suggests that seeing Stonehenge—or beholding the Taj Mahal, or visiting the Louvre, or observing a pride of lions slumbering under a tree in the Maasai Mara—is something that, having been done, can be considered done with.

We have certainly come to value closed-ended experience over open-ended experience, a closed-ended experience being something we can put away, like a pair of shoes or a good technique for long division, and say we have without thinking twice about it. Walker Percy, were he alive, would have something more profound than I to say about it. “Commodification” is often read through the connotation of ability to be bought and sold, but perhaps underlying that is the illusion we can have an experience in the first place. In a psychological sense, the illusion of permanence keeps us from having to think about our mortality (some irony there, in the above article’s context), and there’s obviously an illusion of achievement, too.

We have certainly come to value closed-ended experience over open-ended experience, a closed-ended experience being something we can put away, like a pair of shoes or a good technique for long division, and say we have without thinking twice about it. Walker Percy, were he alive, would have something more profound than I to say about it. “Commodification” is often read through the connotation of ability to be bought and sold, but perhaps underlying that is the illusion we can have an experience in the first place. In a psychological sense, the illusion of permanence keeps us from having to think about our mortality (some irony there, in the above article’s context), and there’s obviously an illusion of achievement, too.

Museums are especially interesting: I spoke with someone who was at the Louvre last summer and felt overwhelmed by her inability to see everything there; FOMO lay around every corner. And I was at the Vatican Museum a couple summers ago, and there were so many people checking the boxes, taking the picture in front of this or that famous piece.

(One more example: has anyone noticed the rise of recreational speed-hikers? Taking down as many miles as possible, with scarcely a look right or left of the trail. A way to convert leisure into work, if ever there were one. The miles represent an “outdoor experience”, but a focus on the measure of that experience, the miles, undermines it almost completely.)

This is the YOLO-ization of cultural experience, whereby the pursuit of fleeting novelty is granted greater value than a patient dedication to an enduring attention—an attention which might ultimately enlarge the self, and not just pad one’s experiential résumé. The notion of the bucket list legitimizes this diminished conception of the value of repeated exposure to art and culture. Rather, it privileges a restless consumption, a hungry appetite for the new. I’ve seen Stonehenge. Next?

What if, instead, we compiled a different kind of list, not of goals to be crossed out but of touchstones to be sought out over and over, with our understanding deepening as we draw nearer to death? These places, experiences, or cultural objects might be those we can only revisit in remembrance—we may never get back to the Louvre—but that doesn’t mean we’re done with them. The greatest artistic and cultural works, like an unaccountable sun rising between ancient stones, are indelible, with the power to induce enduring wonder if we stand still long enough to see.

Maybe it’s the fear that a sustained engagement with something might actually enlarge the self which keeps us from undertaking such an engagement. The world of novelties is certainly more comfortable. Jean-Luc Marion suggests that a true engagement with a rich phenomenon is impossible for me, only because the me after such an encounter is, mercifully, another person altogether from the me who approached it. This seems to be the way faith works; perhaps it’s not so much the consumption of Christian experience, and its accumulation in my heart, as it is a deepening openness to what the New Yorker calls enduring wonder – “be still and know…” Religiously, a principal symptom of our fallenness is our naive attempts to climb out of it, and maybe the strongest evidence of our mortality is our attempts to hedge ourselves around with pseudo-permanence.

2. Got a little carried away there. Less cerebral, but unfortunately no less pessimistic than the New Yorker article, was The Onion‘s announcement yesterday that “80% Of Americans Would Get In Vehicle With Stranger For Chance At New Life“, ht JD:

WASHINGTON—According to a poll released Thursday by the Pew Research Center, 80 percent of Americans would, if given even one opportunity, enter a stranger’s vehicle for a shot at starting a new life. “Our research indicated that as long as the driver was headed somewhere else, anywhere else, more than three quarters of Americans would get in that person’s car without any hesitation,” said Pew spokesperson Sylvia Ettinger, adding that neither the make of the vehicle, its intended destination, nor the appearance or temperament of the driver would have any bearing on the decision. “Provided that entering the vehicle offered even the remotest possibility of a clean break from the past, eight out of every 10 people we surveyed said they were happy to toss their cell phone and wallet into a ditch and put their destiny in the hands of the very first person who pulled over.” The poll found, however, that only 3 percent of Americans would pick up some weirdo standing on the side of the road with his thumb out.

3. Law-Gospel award this week goes to Rachel Rettner at livescience. If you want someone to lose weight, inducing shame may be counterproductive, ht MO:

Harassing obese people, a practice known as “fat shaming,” does not encourage them to lose weight and can actually result in weight gain, a new study from the United Kingdom suggests… About 5 percent said they had experienced such fat shaming. Over a four-year period, those who reported weight discrimination gained about 2 pounds (0.95 kilograms) on average, while those who did not report weight discrimination lost about 1.5 pounds (0.71 kg).

(The counter-productivity of shaming isn’t quite established here, since there’s only correlation – but it does strongly imply that weight-shaming is unproductive. Zero effect at best, and likely negative ones.)

Two observations: (1), weight gain/loss is a perfect example of secular law, something to which Christian ethics are indifferent, but contemporary societal ethics cast as anything but. (2), On a totally separate note, Christianity does talk about repentance as an engine of change – “godly sorrow worketh repentance.” I’m not quite sure how to think about the difference between shame and sorrow over one’s sins, but if humans react the same way to the genuine moral Laws as they do to perceived, secular ones, then studies like this one suggest that change cannot be engineered, and it’s often counterproductive when we try.

4. This is genuinely funny, and very much in line with the New Yorker piece on commodified experience above. I hope this is one of the few times we reference gapyear.com, but they reported that a Dutch girl faked a trip to Southeast Asia. I guess she just hid herself in her bedroom with a couple weeks’ rations while she was supposed to be over there, ht CB:

If you’ve ever spent a rainy evening thumbing through your Facebook newsfeed glaring with scarcely controllable envy at the seemingly endless torrent of pictures posted by unbearably smug friends who are backpacking through some country with scenes so vibrant you wonder if the saturation setting on your screen is faulty, relax.

It could all be a backpack of lies.

For five weeks Dutch student Zilla van den Born subjected her Facebook friends to the above, claiming to be travelling around South East Asia, when in reality she had never left her home city of Amsterdam. She went to extraordinary lengths to perpetuate the illusion, which was fed to her friends and family alike. The only person who knew the truth was her boyfriend.

The above fish is photoshopped. But here it gets pretty good, and we owe a debt of gratitude to Zilla van den Born:

The reasons behind her actions, however, are noble: it was all part of a university project, in which she wanted to show how Facebook activity is not necessarily reflective of real life.

Speaking to media in her home country, she said: “I did this to show people that we filter and manipulate what we show on social media, and that we create an online world which reality can no longer meet.

“My goal was to prove how common and easy it is to distort reality. Everybody knows that pictures of models are manipulated. But we often overlook the fact that we manipulate reality also in our own lives.”

5. There’s a rehab center for Internet addicts, reports The American Scholar, and in a world where instant gratification is at one’s fingertips, it’s welcome when someone starts talking about the implications of it, ht TB:

In a living room overlooking the lawn, 29-year-old Brett Walker talks about his time in World of Warcraft, a popular online role-playing game in which participants become warriors in a steampunk medieval world. For four years, even as his real life collapsed, Walker enjoyed a near-perfect online existence, with unlimited power and status akin to that of a Mafia boss crossed with a rock star. “I could do whatever I wanted, go where I wanted,” Walker tells me with a mixture of pride and self-mockery. “The world was my oyster.”

Walker appreciates the irony. His endless hours as an online superhero left him physically weak, financially destitute, and so socially isolated he could barely hold a face-to-face conversation. There may also have been deeper effects. Studies suggest that heavy online gaming alters brain structures involved in decision making and self-control, much as drug and alcohol use do. Emotional development can be delayed or derailed, leaving the player with a sense of self that is incomplete, fragile, and socially disengaged—more id than superego. Or as Hilarie Cash, reSTART cofounder and an expert in online addiction, tells me, “We end up being controlled by our impulses.”

As a one-time level 73 feral druid myself, I can sympathize. Defeating the Lich King just feels so much more meaningful than, say, writing a blog post. Achievement comes easily and, perhaps more important, linearly in WoW and other online games. By linearity I mean, spend an hour playing, and your character, a surrogate you, measurably improves. You get, say, Dragonstalker Armor, where previously you only had Giantstalker Armor. And you keep it – no threat of loss, no impermanence. And once you’ve improved your character as much as possible, a new update comes out, and there’s more to achieve, more to do, improvements to make.

But World of Warcraft isn’t an isolated phenomenon, nor is the online gaming it’s a part of. It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that WoW is merely an instantiation – though an especially extreme one – of human achievement in general. The outer man is being renewed and improved day by day, while the inner wastes away. Careerism, academia, and many hobbies may work similarly. Spend an hour reading Hegel, and you know more, your outer man is better than before. Push through a big acquisition deal, and you’re in a position to try bigger ones. The creators of Warcraft made one of the most successful games in history not by flashy graphics or great storytelling, but by its understanding of our bent toward achievement.

…the entire edifice of the consumer economy, digital and actual, has reoriented itself around our own agendas, self-images, and inner fantasies. In North America and the United Kingdom, and to a lesser degree in Europe and Japan, it is now entirely normal to demand a personally customized life. We fine-tune our moods with pharmaceuticals and Spotify. We craft our meals around our allergies and ideologies. We can choose a vehicle to express our hipness or hostility. We can move to a neighborhood that matches our social values, find a news outlet that mirrors our politics, and create a social network that “likes” everything we say or post. With each transaction and upgrade, each choice and click, life moves closer to us, and the world becomes our world…

It’s as if the quest for constant, seamless self-expression has become so deeply embedded that, according to social scientists like Robert Putnam, it is undermining the essential structures of everyday life.

Bonus: This week’s Thanks For Not Using Clickbait Award goes to First Things for its non-sensationalistic title, “Of Faith and Doubt: A Theologian’s Comment on a Sociologist’s Theological Category Mistake.” (It’s pretty good.) Al Kennedy at The Guardian wrote a worthy article on how much “aspirational” stuff is marketed to us. Books & Culture gives us more on the Peanuts Gospel. The NYT magazine profiles Lena Dunham, deflecting some of the absurd criticism of her in the process. And some benevolent Youtube person contributes “Star Wars Minus Williams”, below. Also, Jim McNeely’s new book, Grace in Community: Real Life Grace from the Book of 1 John, is out, and we recommend it heartily – more next week.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply