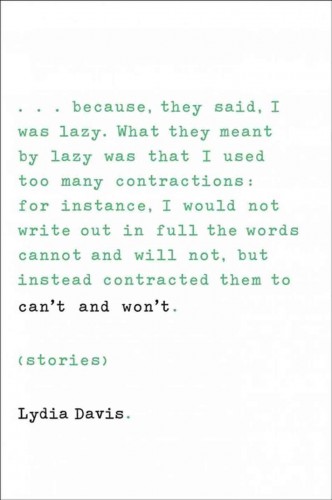

From the MacArthur Genius’ (very funny) book of daydreams, real dreams, and five-sentence memoirs, Can’t and Won’t. Recommended reading for this summer–each entry is mostly no longer than a page, many times without much of a plot–and this one talks about in-flight complications, and the anxious (even superstitious) thinking of the end of one’s life. The pilot has just made an announcement about the wings’ failure to slow the plane down, so it must circle very close to the ground to attempt to slow itself down. Davis journeys back through the way her mind processed this news.

The announcement, from the pilot, terrified me. The terror was very physical, something like an icy bolt down my spine. With his announcement, everything had changed: we might all die within the next hour. I looked, for comfort or companionship in my fear, at the woman in the seat next to me, but she was no help, her eyes closed and her face turned away towards the window. I looked at other passengers, but each seemed absorbed in comprehending what the pilot had said. I, too, shut my eyes, and held on to the arms of my seat.

A little time passed, and then there was a clarification from the steward, who announced approximately how long we would be circling above the airport. The steward was calm. As he spoke, I kept my eyes fixed on his face. This was when I learned something I stored away to remember later, on other flights, if there were to be other flights: if I was worried, I should look at the face of the steward or stewardess and read his or her expression for a clue as to whether I should be worried or not. This steward’s face was smooth and relaxed. The emergency was not one of the worst, he added. I looked across the aisle and met the eyes of a passenger in his sixties who was also calm. He told me he had flown over nine million miles since 1981 and experienced a number of emergency situations. He did not go on to describe them.

A little time passed, and then there was a clarification from the steward, who announced approximately how long we would be circling above the airport. The steward was calm. As he spoke, I kept my eyes fixed on his face. This was when I learned something I stored away to remember later, on other flights, if there were to be other flights: if I was worried, I should look at the face of the steward or stewardess and read his or her expression for a clue as to whether I should be worried or not. This steward’s face was smooth and relaxed. The emergency was not one of the worst, he added. I looked across the aisle and met the eyes of a passenger in his sixties who was also calm. He told me he had flown over nine million miles since 1981 and experienced a number of emergency situations. He did not go on to describe them.

But now the steward was doing something that only intensified my fear: still calm, but perhaps with the calm of fatalism, I now thought, fatalism produced by his long training and experience, or perhaps simply an acceptance of the end, he was instructing the people in the first row point by point what each of them was to do in case he himself became incapacitated. Watching him instruct them, in my eyes they were suddenly elevated from being mere passengers to being his assistants or deputies, and I saw him, already, reduced to helplessness, dead or paralyzed. Even if only in my imagination, the fatal crash was already imminent. At that point, I realized that anything other than routine behavior from a steward or stewardess would alarm me.

Our lives might be almost over. This required an immediate reconciliation with the idea of death, and it required an immediate decision as to the best way to leave this world. What should be my last thoughts on this earth, in this life? It was not a matter of looking for solace but for acceptance, some way of believing that it was all right to die now…

While I was thinking this large thought, my eyes were again shut, I was clasping my hands together until they were moist, and I was bracing my feet very hard against the base of the seat in front of me. It wouldn’t help to brace my feet if we had a fatal crash. But I had to take what little action I could, I had to assert my tiny amount of control. In the midst of my fear, I still found it interesting that I thought I had to assert some control in an uncontrollable situation. Then I gave up taking any action at all and observed another interesting thing about what was happening now inside me–that as long as I felt I had to take some action, I was anguished, and when I gave up all responsibility and stopped trying to do anything at all, I was relatively at peace, even though the earth meanwhile was circling so far below us and we were so high up in a defective airplane that would have trouble landing.

…[The pilot’s] landing was smoother than any I had experienced before. He then slowed the plane very gradually until we were taxiing at a normal speed. He had done a beautiful job of landing, and we were safe.

Now, of course, the passengers all clapped and roared, in their relief, at the same time looking at one another and gazing out the windows in some awe at the fire engines that had not been needed. As the cheering died down, the sound of talking and laughing in the cabin increased. The man across the aisle told me about other near-disasters he had experienced, such as a fire aboard his airplane. We were informed by the steward, who also became more talkative now that we were on the ground, that pilots practice this sort of landing many times in their training. It might have helped us to know this earlier, but perhaps it would not have.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply