Dickens had it right long before Brené Brown did, but she certainly dusts his ideas off a bit.

As an English teacher attempting to ignite within my students’ brains interest in something other than taking selfies, Yik-Yak, or lulu-lemon yoga pants, I find it important to see the value in a text myself before asking my students to read it. We recently finished reading Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations, a novel which I likely Sparknote-d my way through as a freshman in high school (gasp). I just didn’t like it. So I felt a bit of trepidation as we approached this text, fearing that my experience teaching it would be similar to my experience as a reader. And students can smell that. I thought, “There must be something to this book that I missed as a fifteen-year-old,” and I certainly didn’t want my students’ experience reading it to be similar to my own.

As an English teacher attempting to ignite within my students’ brains interest in something other than taking selfies, Yik-Yak, or lulu-lemon yoga pants, I find it important to see the value in a text myself before asking my students to read it. We recently finished reading Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations, a novel which I likely Sparknote-d my way through as a freshman in high school (gasp). I just didn’t like it. So I felt a bit of trepidation as we approached this text, fearing that my experience teaching it would be similar to my experience as a reader. And students can smell that. I thought, “There must be something to this book that I missed as a fifteen-year-old,” and I certainly didn’t want my students’ experience reading it to be similar to my own.

And so I was pleased to find myself not dispelled from the text but drawn into Dickens’ story, primarily because I was simultaneously reading Brené Brown’s Daring Greatly. I couldn’t help but draw parallels between its content and the message Dickens had attempted to impart upon his readers over a hundred years ago: Living to satisfy a societal expectation of who we think we’re supposed to be isn’t truly living.

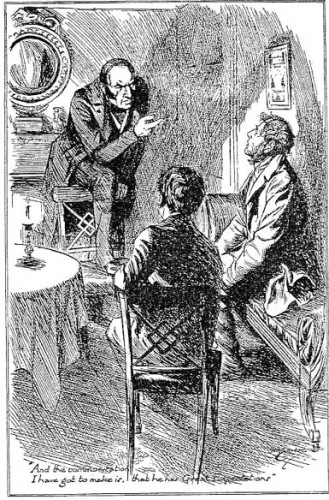

Pip, Dickens’ protagonist, longs for societal advancement. He dreams of being taken away from a life as a humble blacksmith and being made a “gentleman” so that he can be worthy of the woman he loves, who unfortunately is cruel and heartless and manipulative and apparently doesn’t have the capacity to love. Regardless, Pip obsesses over her. Estella by name, fire by touch, this woman symbolizes for Pip all that he must attain to be happy, and yet, even as he is brought up in society and given money, an education, and all the trappings of a true “gentleman,” he only becomes more and more miserable. Even as he spends time with his beloved Estella, he is aware of his own misery. He feels guilt and loss at the life–the identity–he abandoned. He isn’t truly living. He allowed his identity to be so shaped by the expectations he felt society asked him to meet that he was no longer truly “Pip” at heart. He was no longer the kind, unassuming boy from the forge.

In Daring Greatly, Brené Brown invites her readers to examine their struggles with scarcity (being enough and having enough) by asking themselves the following: What are the messages and expectations that define our culture, and how does culture influence our behaviors? We see clearly how Pip allowed his identity to be shaped by the expectations cast upon him by the culture. He changed his behavior to meet the definition of a “gentleman,” and he therefore spiraled away from the young man God desired and designed him to be. The message he heard was: You are not valuable if you are a blacksmith. You are not worthy of Estella’s love as is. Therefore, change. Be like this. Then you will be happy.

What an alluring message: “If I am just like this, then I can be happy?” And we hear these messages every day, in some form or another. We see these “fictional narratives” dance across our computer and television screens, and the inner dialogue starts up. If my list of Twitter followers looked like this. If my baby bump looked as cute as this. If my article on Mbird generated as much interest as this. If my wife wanted our sex life to be like this. If my brain worked like this. As Brené maintains, much of our motivation to change comes out of a “shame-based fear of being ordinary.” Pip literally ran away from life at the forge because he was ashamed of the dirt on his clothes, the way he spoke, his truly ordinary identity. We, too, feel the need to run from being ordinary. We long to be extraordinary and feel shame when we don’t quite make the cut, whatever the “cut” might be. Perhaps even the idea of being an ordinary Christian impacts the decisions we make and the person we “be” around our faith-based communities. But what is so bad about being ordinary? Why do we, when bombarded with these messages, have to choose between either altering ourselves ever-so-slightly (or a-lot-so-slightly) or losing a bit of our value?

What an alluring message: “If I am just like this, then I can be happy?” And we hear these messages every day, in some form or another. We see these “fictional narratives” dance across our computer and television screens, and the inner dialogue starts up. If my list of Twitter followers looked like this. If my baby bump looked as cute as this. If my article on Mbird generated as much interest as this. If my wife wanted our sex life to be like this. If my brain worked like this. As Brené maintains, much of our motivation to change comes out of a “shame-based fear of being ordinary.” Pip literally ran away from life at the forge because he was ashamed of the dirt on his clothes, the way he spoke, his truly ordinary identity. We, too, feel the need to run from being ordinary. We long to be extraordinary and feel shame when we don’t quite make the cut, whatever the “cut” might be. Perhaps even the idea of being an ordinary Christian impacts the decisions we make and the person we “be” around our faith-based communities. But what is so bad about being ordinary? Why do we, when bombarded with these messages, have to choose between either altering ourselves ever-so-slightly (or a-lot-so-slightly) or losing a bit of our value?

Well, we don’t.

It’s just that sometimes, we think we do.

My students seemed to understand this (or so I pray). The fact that my second period has coined the term “pulling a ‘Pip’” to refer to actions done out of fear of how you will be seen suggests that perhaps they heard a thing or two about identity, our culture, and this boy named Pip.

COMMENTS

9 responses to “Too Great of Expectations? Being Ordinary in a Culture of Extraordinary”

Leave a Reply

I needed this today Emily. Thank you.

Thankful it resonated.

So good.

This echoes a lot of some impressions I’ve had lately. An appreciation for the simple and inconspicuous needs to be cultivated if we are to be free from the bondage of selfishness and fear of man. Thanks for posting.

Very interesting. My least favorite Dicken’s book probably because I didn’t understand it.

Wonderful way of summarizing the commonalities in these two books.

I keep rereading this. Such a thoughtful piece. Thanks again for writing it!

Sound like the concept in Sweeden, namely, Lagom.

I’m in AA, and one of our many slogans is “Dare to be average.” Part of what contributes to the success of this slogan is the anonymity of AA. When people come to a meeting they lose their last name, their bank book, their degrees, and their job titles. In other words, we start out with everyone equal. Another slogan even says that the person with the most sobriety is the person who woke up first today. Alcoholics are notoriously (stereotypically) egomaniacs who want to control everything and everyone sometimes “for the good of everybody” and sometimes because we “just know best how to make everything successful.” Step 3 says that “we made a decision to turn our will and our life over to the care of God.” This is not part of the step but part of the step’s description—“Any life run on self-will can hardly be a success.” I’ve found this to be true.

AA is like one of those “books for Dummies. It gives you a direct step by step way to be a better person and get closer to The Higher Power.