When you work too much, you don’t experience events of life so much as you pass them by. The dry cleaning piles up. I need to take those shirts in; I do when I’m down to my last shirt. Without realizing it, the only thing in my refrigerator is a carton of curdled half-and-half and some rotted vegetables. I have some friends, I remember; I’ll catch up with them when work dies down (which it never does). I need to refresh myself on the current events; yesterday I heard something about a lost airliner. At the coffee shop, at two in the afternoon, when I buy my third cup of the day, I read the newspaper headline: Philip Seymour Hoffman died of a suspected heroin overdose. Wow. Did I forget to call the dog-walker today? What time is that next conference call?

Only today, eight weeks later, do I have my experience of his death. The impression that something irrevocable has occurred, that an artist, animated by a subtle and unique spiritual energy, refined in the furnace of human experience, has left us. Or been taken from us. It is impossible to settle on which characterization is more appropriate.

Only today, eight weeks later, do I have my experience of his death. The impression that something irrevocable has occurred, that an artist, animated by a subtle and unique spiritual energy, refined in the furnace of human experience, has left us. Or been taken from us. It is impossible to settle on which characterization is more appropriate.

The most sacred moments in life are not of events or stories or people but of experiences. We see a lot of events and meet a lot of people, but only some people and events give rise to a genuine experience. I recall one experience very well. It occurred during high school, at a grotesquely overlarge cineplex in a half-developed suburb five miles north of where anyone lived—one of those places one finds in the South and Midwest where the movie theaters and the chain restaurants and the Target stores are the foundation of the neighborhood. I was with that friend I should have dated but never did, a fellow idealist whose depth of feeling was unnourished by the milquetoast verities of the suburban bourgeoisie. She had the idea that we see Magnolia.

Three hours after the movie began, we were both speechless and near tears. Many other people in the theater marched out muttering expressions of disgust under their breath. I recall a man, in his fifties or sixties, saying the film was the stupidest he had ever seen. In point of fact, the film was more exciting than the man could bear. It required more probity that he mustered—that he was willing to muster.

An Accidental Lead

Magnolia is still one of the two most gorgeous films I’ve ever seen, along with The Tree of Life. I don’t mean “gorgeous” in the visual sense, because it wasn’t that, and it’s no worse for the fact. Magnolia is a composite story—a story of several apparently unrelated stories from the San Fernando Valley, woven together by events seemingly unforeseen and random, in a world where nothing is really unforeseen and nothing is really random. Director P.T. Anderson draws these events together with a variety of visual styles and against Jon Brion’s pounding, evocative score, which during one phase of the film runs continuously for at least forty-five minutes. The film is draining in a way that art of the highest order always is.

There is Jim Kurring (played by John C. Reilly), the second-rate, bumbling police officer, who responds to a call at the home of Claudia Wilson Gator (Melora Walters), a cocaine addict who the fastidious but lonely Kurring proceeds to ask on a date. Claudia harbors a secret that has caused her estrangement from her father, Jimmy Gator (Philip Baker Hall), host of the whiz-kid quiz show, “What Do Kids Know?” Jimmy’s show pits child geniuses against one another, and, on the last episode Jimmy hosts before he retires, one participant is young Stanley Spector, a boy pressured by his father into winning the show’s generous cash prizes.

Former “What Do Kids Know?” champion Donnie Smith (William H. Macy) watches the episode from a Los Angeles dive, seething from his recent termination from his job at an electronics store that only employed him to take advantage of his D-list celebrity. Donnie hatches a plan to go to unlawful lengths to simultaneously exact revenge on his employer and obtain the money for the dental surgery that will capture the handsome male bartender’s attention. While Donnie clumsily carries out his plan, a former “What Do Kids Know?” producer, Earl Partridge (Jason Robards, in his final role), is dying of cancer. Earl is in hospice care in the living room of his posh mansion, while his much-younger wife, Linda (Julianne Moore), scrambles to both obtain for her own the painkillers prescribed for Earl and, out of guilt for her infidelity, have herself removed from his will. Near death and guilt-ridden for his own sins, Earl wants a final visit from his estranged son, a low-brow Don Juan self-help guru, Frank T. J. Mackey (Tom Cruise).

Earl asks his hospice nurse to track down Frank, so Earl can see him one last time. The wild request sends the nurse, Phil Pharma, on a long-shot investigation beginning on the coldest as of trails—the 1-800-number advertised on Frank’s infomercial. Phil manages to communicate with Frank and looks on in the living room as Frank pours out his grievances against the dying Earl. (The only-in-the-movies quality of the story is intended.)

So numerous are the poignant, compassionate, true-to-lifet performances in Magnolia that I try to resist the urge to describe Hoffman’s Phil Pharma as the “center” or “heart” of the film. But I also find it difficult to resist so describing Phil. Phil is the film’s most quotidian character, the character least participatory in any of the film’s assorted tragedies, the least oppressive and least victimized character, the most closely resembling an observer. His biggest obstacle seems to be fighting off Earl’s aggressive dogs that meet him at the front door.

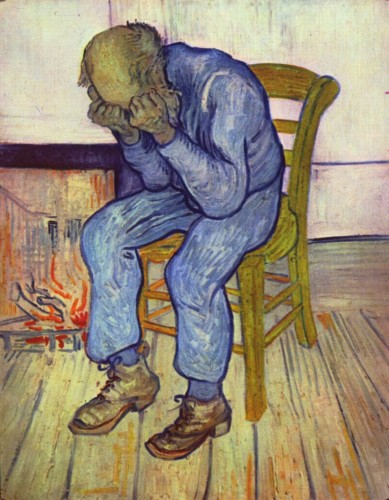

Phil is led into a tragedy at the random stroke of a hospice assignment; yet he becomes a participant by feeling the pain of Earl and Frank. In the way he suffers, Phil draws all the pain of all the film’s characters, all the suffering and all the victimization, onto himself, onto his facial expression of raw confusion and distress. He weaves together the threads of the film into a single fabric—a story of the violence physical, emotional, and psychological that results when the human being’s need for love from others and the human being’s inability to love others smash into one another.

That collision is like one of the desktop perpetual motion machines: so frequent and expected are the collisions that we cease to notice, or we ignore them, or we rationalize them as just part of life. Magnolia aims to awaken us to the tragic dimension of these collisions. In so doing it manages to bring us to compassion for the people responsible for the collisions. Or for the people who are collided with. It is difficult to tell whether any given character is one or the other. And so goes the moral and spiritual wisdom of Magnolia.

An Accidental Charisma

Hoffman had that kind of charisma. In a film featuring beautiful turns from Tom Cruise and Julianne Moore, of course that scruffy, tubby guy whom you wouldn’t pick out of the crowd could not steal the show. No way. And he would be the first to agree. He would stand to the side, content to play his little role, to master his little corner of the universe, as the caregiver of a man dying from old age and wrecked by his regrets and dysfunctions; to portray Phil fighting away those damn dogs who yap at him and bit his ankles; to show him become drawn in uneasily by the old man’s conflicted wife, whose expiation for her is to wretch from herself the fulfillment of being by the old man’s side as he dies; to display the unassuming Phil learn, first incredulously, that the old man’s son is that for-pay pick-up artist from the infomercials, and then desperately try to track Frank down.

That is, Hoffman would imbue with subtle spiritual force a tertiary character who simply acts as a decent human would; he would with utter conviction of experience feel his confusion and befuddlement and incredulity and fear, and we would believe it when Phil acts decently all the same. That was Hoffman’s charisma, his charis, his grace: to model, with an air of accidental goodness, the fear that pervades ordinary, extraordinary consciousness in daily life, as well as the goodness in the face of fear that eludes us.

Hoffman would also have admitted that this goodness eluded him. He had experienced what it was like to be humilis, to be low. And he was aware of what got him there. You could see it in his expression, without knowing anything about the man—that eye of the storm lodged deep within his pupils that tinged his presence with melancholia, which he always brought with him, even in his exuberant roles (I think of the elitist Freddie Miles from The Talented Mr. Ripley, or Hoffman’s unfortunate turn as Lester Bangs in Almost Famous). It was all in the eyes. There was something buried deeply in them that couldn’t be aired in casual company, because casual company was bound to treat the thing with offensive casualness. What was said about Twain could have been said about Hoffman: “He had all of you, but you didn’t have all of him.”

Hoffman could look at you that way because he knew. He knew what it was like to feel it, to have it lurk behind you, to hear the whisper in your ear that disaster is just around the corner, that you had better do everything you can do right now to escape that disaster, and, oh, by the way, there’s no way you can do enough so here comes the disaster.

Hoffman’s most notable breach of his coda of personal privacy occurred in 2006, in an interview with Steve Croft for 60 Minutes. The occasion was his Best Actor nomination for his transcendent role in Capote. Hoffman ultimately won the award, which was a choice that even the Academy couldn’t screw up. In describing his craft, Hoffman explained why he was private about his personal life.

I think part of being an actor is staying private. I do think it’s important. . . Part of doing my job is that [the audience] believe[s] I’m someone else. You know, that’s part of my job. And if they start watching me and thinking about the fact that I got a divorce or something in my real life . . . I don’t think I’m doing my job. . . You don’t want people to know everything about your personal life or they’re going to project that onto the work you do.

There is a glimmer of greater frankness in a word that comes up throughout Hoffman’s interview with Croft. The word is like the wizard behind the curtain as the invisible prime mover in Hoffman’s craft, except the relationship was reversed from that scene we all know. Whereas the gentle and soft-spoken wizard is behind the terrible, oppressive bellow of the wizard on the screen, it was a terrible, oppressive bellow channeled through the gentle, soft-spoken persona of Philip Seymour Hoffman. His art was the channel, the sacramentum, the magical and mysterious consecration of his terror into beauty. But that terrible, oppressive bellow, represented by the recurring word, lurked within him all the same. The word comes up amidst Hoffman’s explanation of the risks in the role of Truman Capote:

Well you do think your career is going to be over all the time. . . I’m actually the one—it’s me, my body, my head, my mind, my voice, it’s right here, and, you know, there is something about people criticizing that or about failing in that realm and that’s hard. That’s hard to take and I do fear that, definitely.

. . . . .

Failing was huge. People knew who [Capote] was. He’s an iconic figure. I just—the fear, the nightmare, the fear of, just, being embarrassingly bad in the role was very real.

The addict’s dysfunction is simply an acute state of every typical form of human dysfunction. There is nothing inhuman about his dysfunction; it is merely accelerated, concentrated, made more immediate and unyielding. And so his acute fear—acute fear being the characteristic of all addicts—is simply the fear experienced by you and me. We tell ourselves that the acuteness of the addict’s fear is irrational, that it is not justified by events, but we ought not be so sure.

The vision of the artist or athlete or businessperson being driven by fear of failure into excellence is by now a cultural archetype, and a celebrated one. Also by now, however, reflective and observant people know what wreckage will come to those who accede to the addiction to fear of failure. Indeed, while that fear may have allowed Hoffman into uncanny displays of the bittersweet beauty of human experience, the fear also killed him. The standard of excellence simply comes with too much pressure. Hoffman was sure to fail his test, if even in his own mind. No one should be surprised that he began abusing once again while playing Willy Loman, the poor man dragged gracelessly into recognition of his mediocrity and the world’s proclamation of his defeat.

On the Justification of Fear

But wasn’t Hoffman just too sensitive? Was it really such a tragedy if he was not actually perfect as an actor in every role he played and in every take and in every scene? You hear this sort of response from time to time when the speaker is faced with a neurotic, or an addict, or the anxious type. The reason you hear it is that, while some people choose perfectionism in response to our nasty fate, some people choose ignorance. One must choose ignorance to really believe that Hoffman was, at bottom, concerned about being perfect at his job as an end in itself. Hoffman was no more single-minded in his obsession with artistic perfection than is a child single-minded shouting “mine!” about his toy. The same goes for the artist or athlete or businessperson who strives for perfection and fears failure.

While there is no doubt a reason the child chooses one toy over another, possession is the pawn in an invisible and big-as-life theater of mimesis, in which the toy mediates the child’s need for spiritual and emotional security. He is fearful of a world without that security. It causes him a terror the depth of which is shielded by the adult’s rationalization that crying is simply the child’s unexplained, natural province. In point of fact, the child doesn’t know what he is without his toy, how he will live without it, who will love him and how he will face the fact that he is unloved without his toy—indeed, whether he will survive.

The toy is the lodestar of the child’s survival. The consequences of his failure to get his toy are disastrous. That Hoffman’s—and anyone else’s—pursuit of glory operates in the same way is why one man’s fear of failure and striving for perfection is significant, why it is not a matter of bourgeois decadence, in a world where a million Syrian children are in exile and starving. The Syrian child, the child lacking his toy, and the actor fear for their survival. How will they survive? And how will they medicate their fear?

I suppose this is the moment where I am supposed to say that fear can be conquered by trusting in the risen Lord or whatever. But I would just as well save the reflex. I would just as well not waste meaningless words to counter the assertion about which Hoffman was exactly right: this world is damn terrifying. It is easy enough to say that fear is an illusion or something trumped-up when you don’t read the newspaper or have a frank conversation with your friend. How could one not be scared in a world where your birth is the beginning of your preparation for death? This is a world of cancer and hunger and beheadings and layoffs and heartbreak and stabbings and innumerable and head-spinning and creative forms of violence and lovelessness. This is a world where people are still burnt alive. That is, in this world there are people who must endure, for several hundred seconds, the sensation of a hot iron enveloping the body until they die of bleeding, inhalation, or organ failure. What sane person would not be terrified in such a world?

COMMENTS

2 responses to “Philip Seymour Hoffman Was Right: A Belated Memorial”

Leave a Reply

I appreciate everything about this article. Thank you, Zach.

https://www.vogue.com/article/philip-seymour-hoffman-mimi-odonnell-vogue-january-2018-issue/amp?__twitter_impression=true