This letter from the editor opens up our first issue of The Mockingbird, our quarterly magazine which has just arrived in mailboxes! To subscribe to The Mockingbird, click here.

“Tell me which kinds of excesses fascinate you, tell me which kinds of excesses appall you, and I will tell you who you are.” –Adam Phillips, “In Excess”

If Phillips is right, and excesses are the ways we are revealed, then there’s plenty to say about what’s been passing through my Newsfeed. Just this week: Kanye West commissions a Kim Kardashian pop-art portrait from one of Andy Warhol’s cousins in Arizona. Andy Warhol’s cousin, Monica, says she wants to do it because Andy would if he were alive, that Kim is manufactured like a Barbie, “famous for nothing.”

If Phillips is right, and excesses are the ways we are revealed, then there’s plenty to say about what’s been passing through my Newsfeed. Just this week: Kanye West commissions a Kim Kardashian pop-art portrait from one of Andy Warhol’s cousins in Arizona. Andy Warhol’s cousin, Monica, says she wants to do it because Andy would if he were alive, that Kim is manufactured like a Barbie, “famous for nothing.”

Also in my Newsfeed: a man in Xuzhou, China leapt seven stories to his death in a shopping mall because his girlfriend would not yield to his pleas to stop shoe shopping. He died on impact in the cosmetics section below.

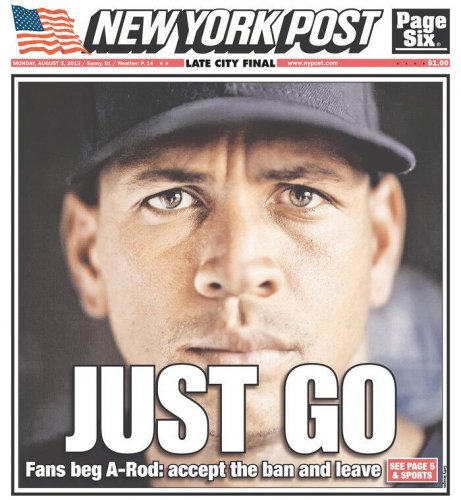

And beyond the inbox there are the everyday excesses, only less concerning because they’ve become so ordinary: market losses and debt ceilings, supersize fries and juice cleanses, left-leaning pinkos and right-wing gun nuts. We watch multimillion-dollar athletes fall under doping allegations and sexting scandals. We are, more than ever, on the lookout for excessive disorders in our loved ones and ourselves: depressive disorders, panic disorders, attention disorders, stress disorders—all of which we read articles on, talk about, worry about. Does she have it? Do I?

What can be said about these fascinations and these horrors? What makes us watch hours of news footage after a shooting spree or an entire season of The Bachelor? Why do we care?

In one sense, we care because we are still—contrary to popular opinion—a religious people. In a year where the “religious nones” have finally taken the polls over those who still worship, this might sound like a suspect conclusion. But I don’t mean it in that sense. I mean, instead, that people still have an idea of God—a standard that marks out what is “too much” from what is “very good, meet and proper.” We may not go to church like we used to, but we still believe in a sense of what’s right. After all, you cannot talk about something being “excessive” or “too much” or “shocking” without having some kind of legal standard in mind. As Phillips writes, “there is something God-like about describing someone’s behaviour as excessive.”

Perhaps, also, these “characters of excess” show us ourselves—our fears, our yearnings, our pasts—in ways that trouble us. Am I smoking too much? Is she giving me the credit I deserve? Is he really that obsessed? Maybe you see where I’m going. The poet T.S. Eliot prays in his poem “Ash Wednesday” (1930):

Teach us to care and not to care

Teach us to sit still

Even among these rocks,

Our peace in His will

And even among these rocks

In a world of excess, in which we are “too much” for each other and “too much” for ourselves, we often turn to something for which we are not “too much,” and when the well drains dry with the government, or flash diets, or Facebook, we might find ourselves with Mr. Eliot, crying amid the rocks for God’s peace: Is there any place where I might unload the burden of these cares?

“Come to me, all you who are weary and heavy-laden, and I will give you rest” (Matt 11.28).

Mockingbird cares about the absurdities of human excess, mainly because we care about what’s really going on in life. We care about suffering people and the world in which suffering people live. What good news, though, that in Christ we hear the invitation to come and rest, in the freedom of not caring. We are given something—someone—for whom we are not “too much,” which means we are given an ungovernable breach in life’s demands for humor, imagination, and hopefully even honesty.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xizNyCM97zA&w=600]

The Mockingbird is a quarterly magazine that hopes to do just this: “to care and not to care.” In articles both short and long, the aim is to present good writing that looks into the lives of people, and to offer there the wisdom and heart of the Christian message of God’s grace. This may include writing about monster ballads or economic policy, college admission rates or modern psychology. We will point to the elemental sameness of some of today’s “contemporary” issues. We will also point to the very foreign hope that still speaks through normal days and old stories.

Typically, each issue of The Mockingbird will be loosely based on a topic (The Social Media Issue, The Family Issues Issue, etc.), though this first one is a more general introduction to our endeavor. Each issue will have a relevant interview; an archive of all kinds of lists; a film- and music-specific column; an anonymous and humorous personal anecdote called The Confessional; not to mention five to seven long-form feature essays.

This issue, we take notes from the original Mockingbird himself, Elvis Presley. We interview Francis Spufford about his recently published work, Unapologetic. We look also into the art of dying in the age of the modern hospital. There are pieces about teachers, preachers, and reality television; police detectives breaking the law, and a son experiencing the onset of his father’s bout with Alzheimer’s. All of these stories are excessive, in one way or another—they wouldn’t be human otherwise. And yet, all of them point us back to the only place where that’s never been and never will be “too much.”

We hope you enjoy.

Ethan Richardson, Editor-in-Chief

SUBSCRIBE NOW!

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply