How do we remember things? At a fundamental level, sensory impressions from the past remain in our minds, as mental images we call forth, things from the past that we re-experience. Recollection often involves distortion – “I certainly never said that, at least not in that tone of voice” – as well as a re-connection with something concrete, objective, outside of us. Memories create our personality as things which inhere always in the mind, latent but present; yet they can also recreate us, redefine us. In Christian terms, we could say that all things are remembered or contemplated by God, both as objective, undistorted fact and simultaneously as things which are narrated, whose interrelations and meanings project and ramify into a tapestry of history, even personal history, with a truth and unity and meaning in the mind of God. From our vantage point, our subjective tendency toward self-justification, as well as our objective cognitive limitation (which themselves are mutually reinforcing), tend to skew our memories and, thus, our identity. In one sense, therefore, repentance and re-habilitation are acts of proper remembrance, of seeing ourselves and the world from the divine vantage point. We do this in a partial and limited way – “through a glass darkly” – but, inasmuch as it is done, it rehabilitates our experience and reconstitutes, in relatively more true way, our relationship to our past, and therefore ourselves, and therefore our world.

How do we remember things? At a fundamental level, sensory impressions from the past remain in our minds, as mental images we call forth, things from the past that we re-experience. Recollection often involves distortion – “I certainly never said that, at least not in that tone of voice” – as well as a re-connection with something concrete, objective, outside of us. Memories create our personality as things which inhere always in the mind, latent but present; yet they can also recreate us, redefine us. In Christian terms, we could say that all things are remembered or contemplated by God, both as objective, undistorted fact and simultaneously as things which are narrated, whose interrelations and meanings project and ramify into a tapestry of history, even personal history, with a truth and unity and meaning in the mind of God. From our vantage point, our subjective tendency toward self-justification, as well as our objective cognitive limitation (which themselves are mutually reinforcing), tend to skew our memories and, thus, our identity. In one sense, therefore, repentance and re-habilitation are acts of proper remembrance, of seeing ourselves and the world from the divine vantage point. We do this in a partial and limited way – “through a glass darkly” – but, inasmuch as it is done, it rehabilitates our experience and reconstitutes, in relatively more true way, our relationship to our past, and therefore ourselves, and therefore our world.

The thinkers of late antiquity tended to associate memory and imagination, as both mental faculties deliberately call forth experiences in the mind, with imagination creating subjective, internal sensory perceptions – sounds, sights, smells, tastes, touches, movements – and memory re-calling those from objective phenomena of the past. Both faculties are functions of the will – we choose to call them forth, we want (at some level) to call these images into existence, making the unreal real or the past present, again. Both memory and imagination, that is, are volitional, always tinged with what we want to imagine. Thus the reserve of experiences we keep stored in the mind are already colored by our subjective feelings, longings, or regrets, and this reserve continues to form us. Some form of this idea must have been apparent to the great Colombian novelist Márquez when he quipped, “What matters in life is not what happens to you but what you remember and how you remember it.”

Tradition-minded thinkers, notably Christian ones or various brands of philosophical reactionaries, would perhaps critique Márquez here for being a ‘relativist’, that is, denying our grounding in objective, real, concrete sensations, encounters with truth which cannot be changed or denied. But the point here isn’t necessarily that we should be shaped by subjective colorings, but rather that we are, and there’s little we can do about it. One of ‘Modern’-isms breakthroughs is this focus on the life of the mind, the truth that we are and cannot help but be subjective creatures, people who filter every perception through our volitions, such that something simple, like a hawthorn-blossom or a particular route for a country walk, can take on dramatic and deeply personal overtones. This coloring takes place not only in the encounter with a phenomenon itself, but also in the encounter at second hand, that is, in its recapitulation within the memory. When the subjective element of experience is reduplicated, its perils are as well; in realizing the unhealthy aspect of this bias, something like rehabilitation occurs. Christian thinkers have often referred to this self-contemplation as repentance, the re-discovering of a reality apart from the self.

The tension between subjective perception and the actual world is a fitting place to start for Proust, who helped inaugurate an anthropological shift in literature in writing his In Search of Lost Time. The indefatigable human will is no longer the center of the story, dominating events in a ‘man of action’ character, but rather it orbits about the object of its desire, devoid of self-possession and reaching out (epektasis) toward something beyond itself. The objects of this desire vary, but for the bulk of Proust’s remarkable opening novel, it is a woman, Odette, and an otherwise stable, brilliant, socially adroit man, Charles Swann, becomes enraptured by her. Swann’s desire for her, coming from some unfathomable place in him, defines him and conditions his every thought and action. He sees her not at all accurately; at one point, he receives an anonymous letter detailing her past promiscuity; his preconceived image of her prevents him from believing a word of it. Something apparent to everyone else is not apparent to him; desire has made the thought unthinkable, the truth calumny.

The narrator, a man in a paralyzed psychological state, desperately trying to reconstruct his life and identity through memory, suffers from the same problem as Swann, an anemic idealism which prepares him for disappointment at every time and prevents him from seeing reality, as he cannot admit of any life-experience which countermands his world of ideas. As the protagonist, his reflections on childhood and adolescence bracket the novel, with Swann’s story of falling in love with Odette in the middle. It’s frame narration at its most effective: by rigorously exploring the tendency of subjective images of the world to distort and isolate reality in protracted case of Swann and Odette, he lays the groundwork for readers to interpolate all the variegated hues of the narrator’s romantic idealism.

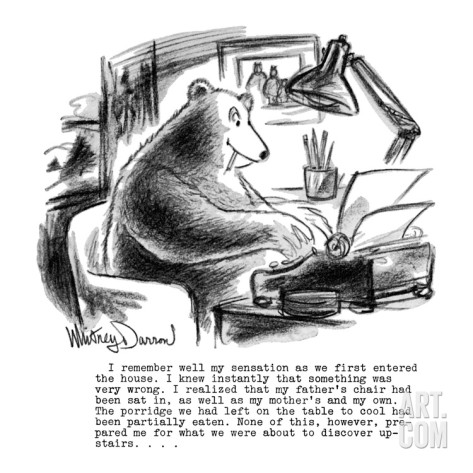

The work opens with the narrator in a state of abstract confusion; his memories and imaginations have collapsed upon themselves into an undifferentiated mass, such that he observes that his memories “following one after another, were condensed into a single substance, but had not so far coalesced that I could not discern between the three strata, between my oldest, my most instinctive memories, those others, inspired more recently… and those which were actually the memories of another.” Untangling these memories, re-enfleshing them and situating them in reality, will be the ultimately redemptive task of the narrator.

In flashing back to Swann’s love of Odette, he learns the pitfalls of emotional projection, how it can remove one from the real world. It’s an act of rehabilitation for him, his hero’s journey of the mind, as he can begin to pinpoint, near the end, his idealist approach to the world. He learns about himself: he remembers wanting to see a storm, “less as a mighty spectacle than as a momentary revelation of the true life of nature”. A contemporary of Proust’s, the modernist painter Cézanne, reportedly said that “You don’t paint souls, you paint bodies; and when the bodies are well-painted, dammit, the soul—if they have one—the soul shines through all over the place.” The narrator cannot rest in the body, but must go straight through to the soul; must behold the essence of things without the form, creating in him “an ideal Time” in which the objects of longing did not exist, an ideal imagination of things for which “I sought to find their counterpart in reality, but… there was nothing that attached itself to my dreams.”

Regardless of Proust’s religious interest, parts of the novel are far more Christian than the ‘man of action’ novels preceding him. The entire novel is a manifesto for the human heart being “deceitful above all else”; the effects of human self-justification and longing for more permeate every encounter the novel describes. And the madeleine cookie, dipped in tea, at the beginning serves as a Eucharistic symbol, spurring not an upward ascent to God but an inward journey of recollection, an inwardness surely lost in more traditional, heroic protagonists.

Regardless of Proust’s religious interest, parts of the novel are far more Christian than the ‘man of action’ novels preceding him. The entire novel is a manifesto for the human heart being “deceitful above all else”; the effects of human self-justification and longing for more permeate every encounter the novel describes. And the madeleine cookie, dipped in tea, at the beginning serves as a Eucharistic symbol, spurring not an upward ascent to God but an inward journey of recollection, an inwardness surely lost in more traditional, heroic protagonists.

Memory, understanding, and will were the three mental faculties which St. Augustine identified in his On the Trinity, a work exploring both God’s Trinitarian nature and the Trinitarian image of God within man. For him, repentance concerned knowing the self as it actually is – as sinner – and such self-knowledge was difficult, disinclined as we are to see ourselves truly. But once the self is seen truly, God can begin to be contemplated as well. Memory, understanding, and will: memory gives birth to understanding, and the will to understand, to contemplate, joins them together, midwifes memory’s journey into the realm of understanding.

For a picture of how this process works with regard to self-knowledge, none is better than Proust, whose narrator is continually struggling to re-collect himself and his world, aided by the sacramental madeleines, the sacramental character of all physical phenomena which, though he loads them down with emotional projections and desires, may yet speak.

To this point, however, we’ve perhaps overread the religious, and it’s worth keeping in mind Albert Camus’s praise of Proust, citing him as one of the finest examples of artistic rebellion against God because of his creation of a self-contained, parallel life of the mind seemingly ex nihilo, manifesting the power of the auto-nomous, creative human spirit. Indeed, for every objective phenomenon in which the narrator regrounds himself, he also perhaps – by the very same subjective element in memory – plunges further into the self-contained interior. And while it would take the entire series to evaluate Camus’s statement, based on this volume it seems he may be missing, partially, Proust’s critique of human self-creation.

When the narrator recalls, as a child, attaching his imaginative fancy to foreign cities, his project there comes across as ridiculous. He remembers that these cities served as fitting vessels for his emotional projection precisely because their definite geospacial existence made them seem real, lending an air of credibility to his images that, nonetheless, could not have been more different from the cities themselves. He anticipates a sudden revelation, an eschatological joy, upon his impending visit to Venice, and when his father makes it seem all the more real by reminding him to pack a greatcoat, he falls ill with anticipation:

…by a supreme muscular effort, a long way in excess of my real strength, stripping myself, as of a shell that served no purpose, of the air of my own room which surrounded me, I replaced it by an equal quantity of Venetian air, that marine atmosphere, indescribable and peculiar as the atmosphere of the dreams which my imagination had secreted in the name of Venice; I could feel at work within me a miraculous disincarnation; it was at once accompanied by that vague desire to vomit which one feels when one has a very sore throat; and they had to put me to bed with a fever so persistent that the doctor not only assured my parents that a visit, that spring, to Florence and Venice was absolutely out of the question, but warned them that, even when I should have completely recovered, I must, for at least a year, give up all idea of travelling, and be kept from anything that was liable to excite me.

There’s a Gnostic element, certainly, in the narrator’s “miraculous disincarnation” into the world of imaginative fancy, his feeling that reality is a mere shell (like the body), to be discarded and filled with projections, desires. His sickness here is one of those rare, perfect symbols in which the literal meaning and metaphorical meaning are perfectly joined; the intensity of emotional projection makes him overexcited and sickened (with a desire to vomit, self-empty) to the point that experiencing the real thing is rendered impossible. And so autonomous creation, the attempt to name into being a world of desire, sickens; he cannot reach out to new places, but must remain trapped in Paris, his present reality, precisely because other realities are not allowed to emerge in their true natures.

To the extent Proust’s work is a critique of religion, an act of rebellion, it is so because it deconstructs our projections. It insists that in idealizing words or places or concepts, we encounter a reduplicated version of ourselves; in trying to uncover ab-solute Reality, we estrange ourselves from daily experience. After his relationship with Odette falls through, in the narrator’s flashback, Swann pursues the Marquise de Cambremer. He had run into her during one of most painful nights of his affair with Odette, and he wants to justify, or redeem, that night by fitting it into a higher purpose. As the narrator wisely muses, his meeting her earlier had seemed providential – Swann’s “mind, anxious to admire the richness of invention that life shews, and incapable of facing a difficult problem for any length of time… came to the conclusion that that the sufferings through which he had passed that evening, and the pleasures, at the time unexpected, which were being brought to birth… were linked by a sort of concatenation of necessity.”

It is this sort of religion which Proust critiques, that of projection of human desires, and dwelling on the errors and missteps of this projection may seem to sever the link to providence, to transcendent meaning. But there is no meaning deconstructed here which is not a self-created one; it is pseudo-transcendence and Feuerbachian fancy which is evacuated, and something like the objective may end up lying underneath. It’s in tracing the way that we read into experiences, and recognizing our distance from reality, that true reality – a true past – may be reconstituted. Thus paradoxically, it’s in Proust’s utter immersion in subjectivity that an objective world may be recovered. Christian eschatological hope, with its focus on the future, had been anthropomorphized into world-historical speculation or grand views of industrial or nationalistic progress; it has been ennervated by the decline of belief. So Proust must go backward into the past to render the present meaningful; for him, backward is ‘inward’, and ‘inward’ – whether through the triumph of human subjectivity or the grace of being determined, passively, from without – may tend toward a movement ‘upward’. It’s an underrepresented direction in traditional Christianity, and one which Proust was well-qualified to draw out. The man of action no longer actualized his future; rather, the neurotic desperately tries to re-collect his past.

As a final note, the novel’s utter mastery of language, in metaphor and image and precise emotions, is truly the work of Camus’s creative force. Past experiences are conditioned by subjectivity; Proust’s narrator relays these in his own subjective language, which Proust subjectively apprehends as author, which we read through our own internal filters. The book, that is to say, explores the problem of communication as much as memory, and it muses on the problems of its own self-disclosure. But the language, as emotionally conditioned as it is, holds out the hope that the words do amount to something, that they can break through. Thus the narrator – and by extension, his author – continue telling the story in hope that meaning will disclose itself, with faith and patience. But Proust’s anthropology , as well as his view of our ability to understand things ‘in themselves’, is low enough that he believes, firmly, we must attend to the problems of understanding before the solution. The work’s great hope is that in re-membering, reconstituting ourselves, the confused images and desires will fall into their proper places, that some real engagement with the world will emerge from an always-fragmented, yet ineluctably ecstatic set of symbols – that the latent unity between the sacramentum and its res can irrupt within our horizon. The converse of this hope is another, simultaneous one: that our anthropomorphic, self-referential fancies will be deconstructed by self-knowledge, that our own efforts to give naïve meaning to ourselves will die. How meaning’s resurrection will happen , ‘what we will be then’, in biblical language, we do not know – but attending to the messy interior is an act of faith, a now-common faith in modern literature for which we largely have Proust to thank.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply