From the festschrift honoring Paul Zahl, Comfortable Words, son Simeon Zahl argues convincingly that God may work in any avenue of human life, broadening the Holy Spirit’s arena beyond the traditional Word (preaching, Bible) and sacrament:

In Isaiah, we are reminded that “All flesh is grass… The grass withers, the flower fades, when the breath of the Lord blows upon it”… the communication of this truth, this broad and profound truth about the futility of merely human activities and strivings in light of death, falls under the remit of the Spirit of truth, despite the fact that it does not immediately or directly reference Christ or his work. Indeed, even for Luther, the reality of death is an important form of how God’s law, in its ‘theological use,’ is preached – the reminder of human mortality and futility can pave the way powerfully for the good news of resurrection and new life in Jesus Christ.

But what about when human beings are reminded of their mortality outside the context of these particular verses of Genesis, Ecclesiastes, and Isaiah, or related ones in the Bible? What about when a person comes to be struck very deeply indeed by the fact that death mocks vain human strivings, but the experience happens not to take place in a church or during a sermon? Consider the extraordinary line from T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”: “I have seen the moment of my greatness flicker / And I have seen the eternal footman hold my coat, and snicker / And in short, I was afraid.” Here, too, the relativizing of human achievement and effort in light of the inevitability of death is communicated with poetry and power. Does the Spirit of truth not work through this truth about death simply because it is in a poem that is not explicitly about Christianity or deliberately patterned on Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection? Can a person not be crushed by this law, and advanced along the pathway of the Gospel, through these lines from “Prufrock” being read in a high school classroom, or on a subway train, or in an armchair at home?

If we still want to insist that ‘No, the Spirit only works in this way through the verbum externum,’ – or, better, that God will not ever speak his ‘external Word’ to us apart from the instruments of Scripture and sacrament – then we are forced into absurdities like these: ‘Perhaps if Eliot had quoted Ecclesiastes directly in the poem…’ or ‘Yes, the Spirit could work through ‘Prufrock’ to prepare the way for the Gospel, but only if the relevant lines are quoted in the larger context of a biblical sermon to a gathering of at least two or three people’… The obvious answer to such questions is that the final presence or not of the Spirit in a given instance is determined by whether or not God freely chooses, through his Spirit, to use the particular instrument or verse, not through subtle analysis of shades of ‘Biblicism.’…

If God’s Spirit animates and sustains the universe God created, the remit of the Spirit of truth must also include creation in all its aspects and workings. An important assumption behind Paul Zahl’s tireless search for profundity and insight across the whole range not just of the Bible and the Christian theological tradition, but also of human history, ideas, art, literature, music, and culture – and his ability to transmute these materials into instruments for communicating about God and the Gospel – is that any real truth about the world or human nature is also God’s truth.

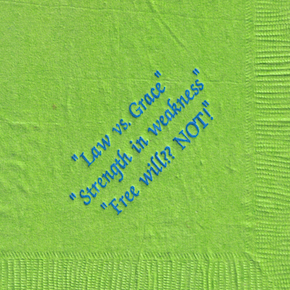

Incidentally, this turns out to be a theological grounding for much of our sometimes-less-than-critical surveys of culture here at Mbird. I’m almost tempted to search for the Spirit’s work in Aztec religion, but (spoiler!) there are some things that can be a bit more peripheral to even the Spirit’s work. On the other hand, if anyone’s needing deconstruction, look no further:

COMMENTS