This insightful and personal reflection on Edvard Munch’s work, as well as the plans for a new museum commemorating it, comes from our friend Daniel A. Siedell.

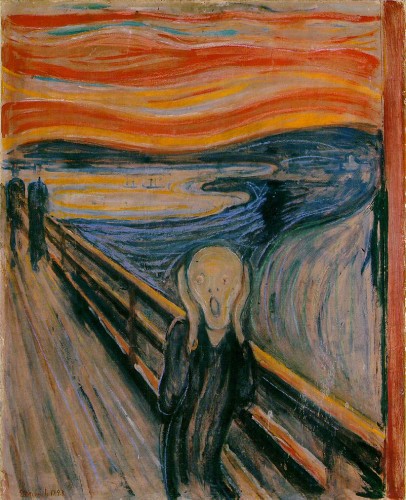

One of my most cherished memories from last year was a trip to New York City to see Edvard Munch’s The Scream on view at the Museum of Modern Art. The painting had made news in May 2012 because it was purchased by New York collector and businessman Leon Black for $120 million, at the time the most ever paid at auction for a work of art.

One of my most cherished memories from last year was a trip to New York City to see Edvard Munch’s The Scream on view at the Museum of Modern Art. The painting had made news in May 2012 because it was purchased by New York collector and businessman Leon Black for $120 million, at the time the most ever paid at auction for a work of art.

But The Scream has been an American pop culture icon since Macaulay Culkin aped the tortured figure’s expression in the classic John Hughes film Home Alone (1990). And the auction result simply enhanced it. MoMA leveraged this notoriety with a gigantic banner of the picture draped from the museum building and a gift shop full of t-shirts, coffee mugs, and other merch. Visitors were also encouraged to photograph themselves doing their best Home Alone imitation in front of the painting and send the results to the museum website.

When I paid my respects last spring I was surprised by how vulnerable and weak The Scream looked, cowering in the middle of an exhibition space crushed by crowds of tourists posing in front of it and flanked by a security guard to keep the peace.

Munch would have been surprised as well, since he believed that his work “might be able to help others to clarify their own search for truth.” About his plans for his work, Munch explained:

There should be no more paintings of interiors and people reading and women knitting. There should be images of living people who breathe and feel and suffer and love—I shall paint a number of such pictures—people will understand the holiness of it, and they will take off their hats as if they were in a church.

The crowd seemed unaware of its holiness.

Munch has exerted a powerful influence on my thinking about the theological implications of art over the course of this past year. My thoughts have focused on a single entry in the artist’s diary:

Art comes from joy and pain…But mostly from pain.

Munch is extraordinarily transparent about how his pictures respond to his pain and suffering. “My art,” Munch observed, “is self-confession. Through it I seek to clarify my relationship to the world.” Munch even referred to his paintings as his “soul’s diary.” And that diary was a painful one, since he spent much of his childhood sick in bed after losing his mother to tuberculosis, and as an adult struggling with addiction and mental illness.

Munch is extraordinarily transparent about how his pictures respond to his pain and suffering. “My art,” Munch observed, “is self-confession. Through it I seek to clarify my relationship to the world.” Munch even referred to his paintings as his “soul’s diary.” And that diary was a painful one, since he spent much of his childhood sick in bed after losing his mother to tuberculosis, and as an adult struggling with addiction and mental illness.

And yet the messages we often receive from advocates for art, both inside and outside the church, is that art is a means to escape or overcome pain and suffering—art communicates transcendent values; celebrates creativity; shapes community; participates in human flourishing and the common good; and forms morality.

Commentators often marginalize artists like a Munch (or a van Gogh), for whom pain and suffering cannot be swept under the rug by interpreting them as exceptions and curiosities, the broken ones whose pictures we simply gawk at and shake our heads at how messed up their lives were (perhaps because of their faulty worldviews). This raises an impenetrable barrier (or opens up an ugly ditch) between the vulnerability of those works of art and ours, preventing them from connected to our pain, our vulnerability, our own broken and messed up lives.

I can understand why. Pain and suffering are buzz-kills, and they’re blows to the business of art and culture, the business of cultural commentary. I am often criticized by those inside the church for promoting the modern “myth” of the tortured artist, of exaggerating the role of suffering in the artist’s life. But from my experience of working with artists for over twenty years, I cannot recall a single artist whose work did not come from a still-festering wound, and usually a childhood one. The fact is, the arts attract sufferers.

We are more like Munch than the cultural gatekeepers inside and outside the church care to admit. The first lines of Albert Camus’s The Stranger are, more often than not, the first lines of our own personal narratives:

Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday. I can’t be sure.

If you think this is an exaggeration, we only need to point to the fact that Louis C.K.’s riff on cell phones and suffering on Conan O’Brien’s show this past September went viral, with over six million views (profanity warning).

This past summer the city of Oslo, Norway, celebrated the 150th anniversary of Munch’s birth with the announcement of plans to build a spectacular new building for the museum dedicated to his work. Designed by Spanish architect Juan Herreros, the concrete building wrapped in a glass shell will offer three times more space to exhibit Munch’s work. It will also revitalize the city of Oslo. Located on its Bjørvika waterfront, the new Munch Museum will be the main art attraction among other cultural organizations, shops, restaurants, hotels, homes, and offices that will, over the next few years, replace the docks and shipyards.

Not long before his death in 1944, Munch bequeathed to the city of Oslo all of the remaining work in his studio: 1,100 paintings, 3,000 drawings and watercolors, and 18,000 prints. This consists of over half of his total output throughout his five decades as an artist.

This means that Munch could not or would not sell half of his total artistic output.

As evidence from his diaries and letters, it was a constant struggle to sell his work. Much of the work remained in his studio because he could not find buyers.

But there were also many paintings that Munch did not want to sell. He wanted those “self confessions” around. Toward the end of his life, living alone in his large, dark, and empty home, suffering from loneliness and insomnia, he painted full-scale portraits of his friends and mentors. He called them “guardians” and placed them around the house to keep him company during his restless late-night wanderings through the house. He wanted some of these paintings to remind him of the discoveries about his life that he made when he painted them and to offer him comfort.

But there were also many paintings that Munch did not want to sell. He wanted those “self confessions” around. Toward the end of his life, living alone in his large, dark, and empty home, suffering from loneliness and insomnia, he painted full-scale portraits of his friends and mentors. He called them “guardians” and placed them around the house to keep him company during his restless late-night wanderings through the house. He wanted some of these paintings to remind him of the discoveries about his life that he made when he painted them and to offer him comfort.

And they also served to fill the hole created by the death of his older sister, Sophie, who died at fifteen years old, when the artist was a boy. Munch’s biographer, Sue Prideaux, suggests:

Sophie’s death was a blow from which Edvard never fully recovered. A desolate longing for her remained all of his life. He had lost his mother all over again. God had broken his promise… But Edvard did not rant or threaten, deny his God or curse his blood. The gulf between his interior and exterior life merely became wider and more permanently fixed.

The new Munch Museum will be a remarkable achievement when it opens in 2018. The global art world will descend upon Oslo, and the city will be celebrated as it valorizes its national artistic hero. The museum will help revitalize the city and to re-energize Norwegian culture. It will also enable more of the artist’s work to be on view and thus offer a more detailed picture of the experience which Munch sought to record.

But it just might widen the gulf between his suffering and ours.

Munch recalls that right before his sister Sophie died, she asked to be taken from her bed to a nearby chair. And with Munch and the rest of his family with her, she died in that chair. Over the course of his career, he painted six different versions of that moment.

In addition, Munch kept that chair with him the rest of his life.

Somewhere in that beautiful new building, when it opens to exclusive black-tie celebrations and public events, that chair will be on display, a silent witness to the absent life which drove Munch as an artist and as a man.

I spent a lot of time in art museums this past year, and as I reflect on those experiences and paintings that have had a powerful impact on me, Munch’s empty chair seems to have been there. But what I have come to realize is that the chair isn’t Munch’s.

It is mine.

Daniel A. Siedell is Presidential Scholar & Art Historian in Residence at The King’s College in New York City and Curator of LIBERATE, the resource ministry of Tullian Tchividjian & Coral Ridge Presbyterian Church in Fort Lauderdale.

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply