Reading books about how to be happy can be a depressing business… It doesn’t take a social scientist to see that a blizzard of how-to books on “positivity” suggests its lack in everyday life. Behind the facade of smiley-faced optimism, American culture seems awash in a pervasive sadness, or at least a restless longing for a sense of fulfillment that remains just out of reach…

Thus begins Jackson Lears’ extraordinarily insightful overview of the recent swath of Happiness books for The Nation. “Overview” doesn’t do the piece justice, though. Lears has provided us with both a history of happiness (in this country at least) and a stunning indictment of what is currently being passed off in its name. The areas of Mbird overlap are significant, too, and not just in how he weaves in religion (though there is a nice shout-out to Protestantism at the end). We all want to be happy, of course. Lord knows there’s nothing wrong with that, as far as it goes. But Lears traces what happens when Happiness–rather than its pursuit–is understood as a right and not only that but a moral Good. As you might expect, the incurvatus in se of the human creature runs rampant, producing the twin offspring of entitlement and imperative (Thou Shalt Get Happy!), a combination which ironically doubles as a recipe for misery, it would appear. Lears’ other chief observation has to do with how these books, and perhaps the discipline itself, contain an over-reliance, and ultimately cruel insistence, on willpower as the primary/sole engine of wellbeing. If you don’t have enough, then you’re unfortunately out of luck. Which may sound overblown, but as you’ll see, Lears is not interested in softening any blows. A few takeaways:

Thus begins Jackson Lears’ extraordinarily insightful overview of the recent swath of Happiness books for The Nation. “Overview” doesn’t do the piece justice, though. Lears has provided us with both a history of happiness (in this country at least) and a stunning indictment of what is currently being passed off in its name. The areas of Mbird overlap are significant, too, and not just in how he weaves in religion (though there is a nice shout-out to Protestantism at the end). We all want to be happy, of course. Lord knows there’s nothing wrong with that, as far as it goes. But Lears traces what happens when Happiness–rather than its pursuit–is understood as a right and not only that but a moral Good. As you might expect, the incurvatus in se of the human creature runs rampant, producing the twin offspring of entitlement and imperative (Thou Shalt Get Happy!), a combination which ironically doubles as a recipe for misery, it would appear. Lears’ other chief observation has to do with how these books, and perhaps the discipline itself, contain an over-reliance, and ultimately cruel insistence, on willpower as the primary/sole engine of wellbeing. If you don’t have enough, then you’re unfortunately out of luck. Which may sound overblown, but as you’ll see, Lears is not interested in softening any blows. A few takeaways:

1. According to Mears “nowhere is scientism more flagrant than in the contemporary science of happiness.” He writes:

“Scientism is a revival of the nineteenth-century positivist faith that a reified “science” has discovered (or is about to discover) all the important truths about human life. The scientism on display in the happiness manuals offers a strikingly vacuous worldview, one devoid of history, culture or political economy. Its chief method is self-reported survey research; its twin conceptual pillars are pop evolutionary psychology, based on just-so stories about what human life was like on the African savannah 100,000 years ago, and pop neuroscience, based on sweeping, unsubstantiated claims about brain function gleaned from fragments of contemporary research. The worldview of the happiness manuals, like that in other self-help literature, epitomizes “the triumph of the therapeutic” described some decades ago by the sociologist Philip Rieff: the creation of a world where all overarching structures of meaning have collapsed, and there is “nothing at stake beyond a manipulatable sense of well-being.” With good reason, Rieff attributed the triumph of the therapeutic to the shrinking authority of Christianity in the West…

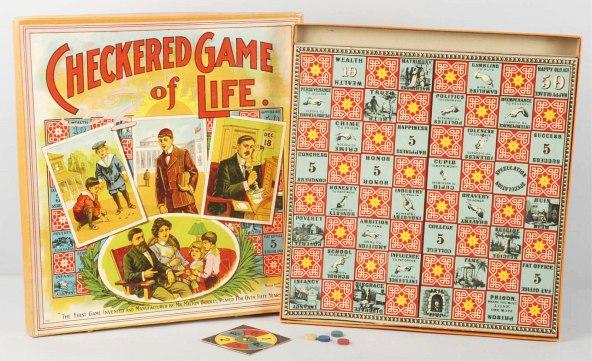

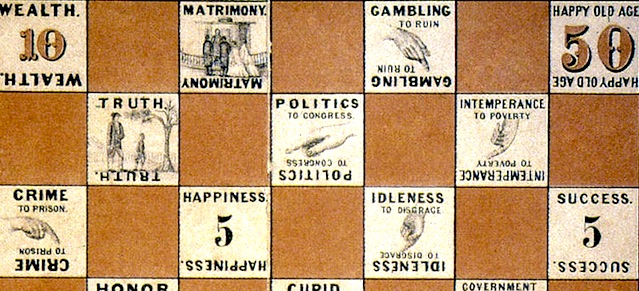

No believing Christian could doubt that abiding happiness was reserved for the afterlife, while this earthly realm remained dominated by struggle and sorrow. But by 1860, signs of slippage from this orthodoxy were apparent, even in such didactic board games as Milton Bradley’s Checkered Game of Life, which ended (if you were lucky) in Happy Old Age. In 1960, to commemorate the centennial of the Checkered Game, the Milton Bradley Company issued another version, the Game of Life. Instead of virtue rewarded by heavenly happiness… the Game of Life offered “a lesson in consumer conformity, a two-dimensional Levittown, complete with paychecks and retirement homes and medical bills.” Players who successfully navigated their tiny station wagons along the Highway of Life could retire, at length, in Millionaire Acres.

2. With one exception, each of the authors’ version of happiness coincides very nicely with their own identities. That is, without an abiding external point of reference, we tend to recreate happiness in our own image, which, given the folks writing these books, looks suspiciously like that of Type-A, first-world secular academics.

3. The inflated anthropology being presumed in these manuals is what assures their failure, or at least, infamously short shelf-life. Some might call it a modern version of the age-old fallacy that if a person simply knows what they need to do (the Law), they’ll be able to do it, that the issue is with unhappy people is primarily educational, etc. He claims that “the emphasis on the sovereignty of choice is uncharacteristically single-minded.” Hand in hand with this emphasis we find a widespread preoccupation with “growth”, which Lears rightly points out as a relatively recent phenomenon (one that the church has swallowed whole hog). As a result, these books are not benign exercises in fantasy; they actively set already unhappy people up for despair. He writes:

“[The Myths of Happiness author Sonja] Lyubomirsky’s silliness would be merely annoying, except that it betrays a fundamentally flawed method, based on the assumption that her audience has unlimited freedom. If you feel trapped in a dead-end job, just “shift your priorities and goals… from running a bank to running a nonprofit, from wealth to philanthropy, from teaching to writing, or from writing to teaching.” And “if there are repetitive or dead spells in your work, perhaps you can take advantage of them by growing in some way.” Indeed, “growth” is her mantra. So you’re divorced? It’s not the end of the world, not nearly as bad as you think. Pull up your socks, “rise to the occasion and push forward.” You will find that “after divorce, you will cope and grow,” and turning the episode into a “growth experience” means you can “bounce back…and even emerge from it stronger than before.” If all this sounds familiar, it is because the creed of “growth” has been therapeutic orthodoxy ever since Abraham Maslow’s notion of a “hierarchy of needs” swept the profession in the 1960s.

As The Myths of Happiness reveals, many therapeutic mantras have remained unchanged for fifty years. There is, for example, the reminder of the importance of “being spontaneous” for keeping a relationship fresh, with the same inattention to the contradiction involved in willed spontaneity. There are also the familiar formulas for avoiding excessive consumption. Beware the “hedonic treadmill”: because we adapt quickly to new pleasures, we are always upping the ante, always turning yesterday’s luxuries into today’s necessities. This is the consumerist dynamic we need to keep in mind as we contemplate our next purchase, even as (the manuals mostly assume) we will make that purchase anyway. “Spend your money on experiences rather than possessions,” Lyubomirsky advises, and turn your things into experiences: “We could take along our family and friends in an adventure in our new car; we could throw a party on our new deck; and we could practice a self-improvement program on our new smartphone.” Ben Franklin would be pleased. So would Teddy Roosevelt: action is all...

Despite its resolute avoidance of social questions, The Happiness of Pursuit implicitly endorses a neoliberal vision of gradual self-betterment through personal choice… The happiness industry’s obsessive focus on the inner dynamics of the choosing individual. For the positive psychologists, change is a product of restless human choice–the recognition of impermanence reinforces a commitment to constant “personal growth.”

4. Lears’ favorite of these books is written by Robert and Edward Skidelsky (great title: How Much Is Enough?), but the one that sounds most intriguing to me is Oliver Burkeman’s Happiness For People Who Can’t Stand Positive Thinking, which we’ve mentioned previously:

For Burkeman, change is a consequence of cosmic conditions beyond human control; “real happiness,” he writes, “might be dependent on being willing to face, and to tolerate, insecurity and vulnerability.” Indeed, “acceptance of impermanence” is a condition for connections with others. He quotes C.S. Lewis: “To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything and your heart will be wrung, and possibly broken.” Ultimately, Burkeman recommends cultivating what Keats called “negative capability,” the state of mind that occurs “when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

5. Next, and this should probably come as no surprise, freed from any religious mooring, “the distinction between needs and wants has all but disappeared from the academy. The discovery that wants could be recast as needs, that luxuries could be transformed into necessities, has allowed the engines of economic growth to run endlessly.”

6. I enjoy reading the results of the latest social science survey as much as the next guy, but when it comes to happiness, Lears is on to something when he takes issue with self-reporting. This is not unlike asking people to answer a survey about how sanctified they are, i.e. the topic itself almost precludes reliable answers:

“The contemporary science of happiness, they write, “rests far too much faith on the accuracy of the survey data. More disturbingly, it treats happiness as a simple, unconditional good, measurable along a single dimension. The sources or objects of happiness are disregarded. All that matters is whether you have more or less of the stuff. These are false and dangerous ideas,” not least because they systematically ignore the larger interactions of the self and the world. According to the Skidelskys, “self-reports cannot be the ultimate criterion of happiness, however useful they might be as supplementary evidence…. Happiness…is not an item in the mind’s inner theatre, visible only to its owner; it is essentially manifest in acts and happenings.” Happiness, in short, is about being in the world with others.

I should probably note that this is part of what makes Jonathan Haidt’s Happiness Hypothesis such a breath of fresh air. Not only does he rely on research that is significantly more sophisticated than the self-reported survey variety, he looks beyond the normal evolutionary alleys into literature and religion and philosophy.

7. Finally, The Nation might not exactly be the first place one would expect an endorsement of universal Good. Lears gets points for daring-do, when he references, toward the end, of the piece, one of the Skildelsky’s conclusions:

“Our continuing addiction to consumption and work is due, above all, to the disappearance from public discussion of any idea of the good life.” And discussion is what it takes, not “counting heads or going around with a questionnaire.” Elements of the good life include “health, respect, security, relationships of trust and love.” These are not simply means to the good life; they are the good life. Such basic goods are universal (“they belong to the good life as such, not just some particular, local conception of it”), absolute (“good in themselves, and not just as a means to some other good”), sui generis and indispensable.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YnkAuIIv0eU&w=600

7.5. More of a P.S., I suppose, there’s the incredible Thomas Carlyle quote, written in 1843, critiquing the notion that happiness is both the chief aim and end of human life:

“Every pitifulest whipster that walks within a skin has had his head filled with the notion that he is, shall be, or by all human and divine laws ought to be, ‘happy.’ The prophets preach to us, Thou shalt be happy; thou shalt love pleasant things, and find them. The people clamour, Why have we not found pleasant things?”…

COMMENTS

Leave a Reply