In September of this year, we missed an interesting article over at the The Guardian profiling the then-governor of Bastoy Prison, one of the most successful prisons in the world, located in Norway. ‘Success’ immediately raises the question of what success looks like, and we could say there are two major approaches to this term: the first, ‘success’ in terms of making inmates less likely to reoffend, and second, ‘success’ in terms of how much prisoners serve a just punishment equal to their crime.

The second seems a bit vindictive, though most people would be if they were the victims of these crimes. The strange thing is, non-victims in America often talk about the need ‘tough on crime’ and, regardless of how much most of us would want to distance ourselves from this vindictiveness, the attitudes of the US electorate have clearly said otherwise. First, the facts from The Economist, in an August 2013 article:

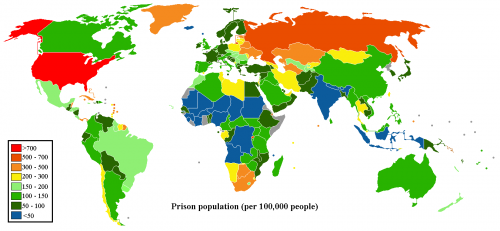

America has around 5% of the world’s population, and 25% of its prisoners. Roughly one in every 107 American adults is behind bars, a rate nearly five times that of Britain, seven times that of France and 24 times that of India. Its prison population has more than tripled since 1980. The growth rate has been even faster in the federal prison system: from around 24,000—its level, more or less, from the 1940s until the early 1980s—to more than 219,000 today.

Statistically, it’s difficult to ignore the high correlation between America’s harsh prison systems and its products’ comparatively high likelihood of being arrested again, which is 67% within three years out. Harsher sentences making people feel more resentment (at best) or suffer more psychological/physcial damage (at worst) and ultimately making behavior worse? Maybe it’s just me, but I think Luther could have a field day with that.

In an earlier, July 2010 article, The Economist probed some of the impulses behind the current state of our criminal system, claiming we have “A long love affair with lock and key”:

In 1970 the proportion of Americans behind bars was below one in 400, compared with today’s one in 100. Since then, the voters, alarmed at a surge in violent crime, have demanded fiercer sentences. Politicians have obliged. New laws have removed from judges much of their discretion to set a sentence that takes full account of the circumstances of the offence. Since no politician wants to be tarred as soft on crime, such laws, mandating minimum sentences, are seldom softened. On the contrary, they tend to get harder…

Half the states have laws that lock up habitual offenders for life. In some states this applies only to violent criminals, but in others it applies even to petty ones. Some 3,700 people who committed neither violent nor serious crimes are serving life sentences under California’s “three strikes and you’re out” law. In Alabama a petty thief called Jerald Sanders was given a life term for pinching a bicycle. Alabama’s judges are elected, as are those in 32 other states. This makes them mindful of public opinion: some appear in campaign advertisements waving guns and bragging about how tough they are…

You don’t have to be a sociologist to posit a link between our love of being ‘tough on crime’ and the comparatively prominent role of Christianity in our public discourse. Of course, Christianity is not directly a religion of punishment, but in many forms it has been strongly interpreted as a religion positing each individual’s responsibility for his or her moral self-development and free choice. Economically, we want every single person to have an opportunity, and perhaps that dream is largely realized, though levels of opportunity and chances of ‘success’ can vary widely. But the American Christian corollary, that there is full freedom and an attendant responsibility for one’s own virtue, is more spurious, at least on Christianity’s own terms. A Christian view of human nature might contribute to the conversation by exposing our primal desire to be better than ‘those’ people – “I’m no murderer!” Heaping condemnation on people who have acted it out probably makes us feel superior, but God did, after all, say that “Whoever kills Cain will suffer a sevenfold vengeance.” And I’m not an ethicist, and can’t legislate on the death penalty or anything, but we can all benefit from the Bible’s psychological acumen here. The ethics of this statement could be read as secondary; primary is the exposing of our desire to be the executors of justice as our own dollop of original sin – regardless of whether or not such justice is ‘necessary’.

Justice is a necessity, for dangerous people to be in a place where they do not pose a threat to anyone (except the other inmates, more often than not), and to (hopefully) provide some sense of closure to victims. But actual renewal of life doesn’t seem to be among our justice-oriented goals, at least not in the last few decades.

To return to Norway – isn’t it annoying how people are always referencing ‘Norway’ as the progressive utopia? – and Bastoy Island, the reoffending rate is a scant 16%. This differential is of course due to more than just prison policy – education levels, mental health statistics, and socioeconomic factors probably play a part – but still the difference seems significant. None of Bastoy Island’s example is to say the US or anyone else should directly emulate it, necessarily, given our country’s distinct, non-Norwegian character; it’s more to point out that there’s probably potential somewhere for a more grace-savvy prison system to also work, that people do tend to react better to respect/rehabilitation than they do to strictly punitive measures, and that we can perhaps even observe some of (little-g, human grace’s scandal) in our reactions to Bastoy, ht SMB:

Under Nilsen’s tenure, Bastoy, home to some of the most serious offenders in Norway, has received increasing global attention both for the humane conditions under which the prisoners live – in houses rather than cells in what resembles a cosy self-sustaining village, or what the sceptics have often described as a “holiday camp” – and for its remarkably low reoffending rate of just 16% compared with around 70% for prisons across the rest of Europe and the US. Last year alone, the island, not much bigger than a breakwater in the Oslo fjord, played host to visitors from 25 international media organisations, all keen to find out the secret of Nilsen’s success…

“I run this prison like a small society,” he says as we sip tea in his cramped but tidy office. “I give respect to the prisoners who come here and they respond by respecting themselves, each other and this community.” It is this core philosophy that Nilsen, 62, believes is responsible for the success of Bastoy…

“It is not just because Bastoy is a nice place, a pretty island to serve prison time, that people change,” says Nilsen. “The staff here are very important. They are like social workers as well as prison guards. They believe in their work and know the difference they are making.”…

“I don’t think I will ever be able to do that,” says Nilsen. “If someone did very serious harm to one of my daughters or my family … I would probably want to kill them. That’s my reaction. But as a prison governor, or politician, we have to approach this in a different way. We have to respect people’s need for revenge, but not use that as a foundation for how we run our prisons. Many people here have done something stupid – they will not do it again. But prisons are also full of people who have all sorts of problems. Should I be in charge of adding more problems to the prisoner on behalf of the state, making you an even worse threat to larger society because I have treated you badly while you are in my care? We know that prison harms people. I look at this place as a place of healing, not just of your social wounds but of the wounds inflicted on you by the state in your four or five years in eight square metres of high security.”…

He believes that politicians carry a huge responsibility for the number of people in prison around Europe and the commensurately high reoffending rates. “They should deal with this by rethinking how they address the public regarding what is most effective in reducing reoffending. Losing liberty is sufficient punishment – once in custody we should focus on reducing the risk that offenders pose to society after they leave prison. For victims, there will never be a prison that is tough, or hard, enough. But they need another type of help – support to deal with the experience, rather than the government simply punishing the offender in a way that the victim rarely understands and that does very little to help heal their wounds. Politicians should be strong enough to be honest about this issue.”

COMMENTS

8 responses to “A “Love Affair With Lock and Key”: Reflections on Criminal Justice”

Leave a Reply

Ok, let’s talk. I think we can all agree that the prison system stinks. And surely one of the best things we can do is start treating prisoners more like human beings (which may or may not mean getting them out of our current disastrous system altogether). I also think, personally, that the federal ‘mandatory minimum’ sentencing in many states is a HUGE part of the problem. And I think you’d probably agree. So far so good.

But it seems, in this post, you are also, perhaps inadvertently, making some pretty hefty theological claims, about justice in particular. And that’s where I get…flustered.

Let’s be honest. It’s easy to say that something like “our love affair with lock and key” is a problem when you don’t actually philosophically believe that there is a real thing called ‘justice’–i.e. that doing justice is ever really justifiable. You conclude that when God protects Cain from earthly vengeance, he is not only (probably) condemning capital punishment altogether (though he clearly affirms–no, commands–it in Gen. 9:6 and countless times after), but he is even more certainly, as you put it, exposing “our desire to be executors of justice as our own dollop of original sin.” In other words, you have actually linked the desire for justice with SIN. Yes, the very thing which God commands his people time and again to “do,” the very thing the Psalmists time and again beg God to do, the very thing Paul proclaims that God has done through Jesus, and moreover the very thing Paul commends the secular authorities of his time as “ministers of God” for doing, you suggest is fundamentally a mark of human SIN.

To be fair, perhaps you would respond that there you were speaking primarily of “vengeance.” Fair enough. But still, what I am trying to point out is that whole crux of your argument depends on you not actually believing in a real thing called “justice.” But wait…Later you state:

“Justice is a necessity, for dangerous people to be in a place where they do not pose a threat to anyone (except the other inmates, more often than not), and to (hopefully) provide some sense of closure to victims. But actual renewal of life doesn’t seem to be among our justice-oriented goals, at least not in the last few decades.”

So to summarize, the thing you’re calling “justice” can be kind of good when it deters future crimes (though it doesn’t do it well), and it can be kind of good when it provides closure to victims, though it doesn’t do that well either. But, you say, we’ve forgotten in recent years that this “justice” should also include positive reform of the criminal.

All true enough, I suspect. But here, of course, you’re talking about earthly, practical justice–about criminal justice in particular. And you’re saying, I think, that it doesn’t tend to work very well, because it lacks mercy; it lacks grace. That may or may not be so, practically speaking. I think I tend to agree with you.

But the point I am trying to make is that the whole basis of our practical criminal justice system must be based in a deeper thing called actual, real JUSTICE, or else all is lost. (Most of this I am now stealing from C.S. Lewis’s essay “On the Humanitarian Theory of Punishment”, so check that out if you’re interested.) What I’m trying to say is, we have already gone astray if we start making arguments regarding criminal justice based merely on such practical concerns as “deterrence, closure, and reform.” Before any of that enters the picture, there has to be an actual belief in justice, goodness, fairness, deserving. The only way to deal with a criminal ‘justly’ is to begin the process according to what he deserves. We have no right to put someone in prison at all–whether it be a wonderful Norwegian one or a hideous American one–unless he deserves something of that nature. We could start punishing people everywhere for crimes they didn’t commit and it might effectively deter guilty parties from continuing their crimes, but of course that would be unjust. And the same is true of the most merciful “mandatory reform programs.” If you don’t begin with that archaic thing called “deserving” then you have no grounds to do anything at all with those who seek to kill and harm and steal.

In other words, what I’m saying is that one has to believe in real justice–in real deserving–if one is to enter this conversation at all without making a mockery of it. If the idea of “deserving” is antiquated, misinformed, or even sinful, then of course prisons are awful. Of course the death penalty is inhumane. But then, how can one talk about those issues at all? Such moral positions would have no basis in reality. All there would be is natural selection and those who (for the sake of unfounded mercy) choose to ignore it.

Which is why, again, I say: My concern here is not with your views on practical criminal justice per se,

but with the larger theological implications of your argument. Because if there is no such thing as justice, how could there be such a thing as mercy? How could there be such a thing as grace? Such ideas derive their power from the primary assumption of justice (goodness triumphing over evil) as reality. But what if it were possible to take the idea of “grace” by itself to such an extent, that we forget—or even begin to reject–the primary reality from which it arose and responded? In other words, if grace means to benevolently receive the opposite of what you deserve, but our idea of grace has led us to believe that deserving no longer matters, then alas, our idea of grace has led us to the dismantling grace itself.

I know–I am sure–that I have made a straw man of your argument to some degree, Will. And for that I apologize. I do realize that my primary argument – that you do not seem to believe in justice – is in a very real sense untrue. But at the same time, it seems that your theology, as it is articulated here, does NOT believe in justice, or perhaps has neatly packaged the whole idea into a vague and distant notion of mechanistic Old-Testament-God perfectionism/anger, now shattered by Jesus, the loving God of the New Testament (which leads to the same conclusion). In fact, it might not be extreme enough to say that you don’t believe in justice, because in truth, it seems you’re actually arguing that justice is the sinful creation of human beings. But again, I am risking creating more straw men out of you. So, if you please, let’s continue the conversation. Or if not here, I totally understand. I’ll buy you coffee next time I’m in Cville!

Thanks Ross. Coffee in Cville sounds great – I’ll give you brief thoughts in the meantime though. There is an entity or “form” called Justice, and in those terms, “the just” is probably identical with “truth, goodness”, etc, i.e., God. I regret any undertones in the piece suggesting otherwise. I think the problem here is perhaps epistemological – i.e., what are the epistemic, or noetic, effects of the Fall?

You say that “If you don’t begin with that archaic thing called “deserving” then you have no grounds to do anything at all with those who seek to kill and harm and steal.” I agree – very strongly in theory and somewhat less strongly in practice. The divine form, or true identity, or whatever we want to call it of justice is different from our conception of it. How different it is would perhaps be part of our point of difference. To what extent or degree is our pursuit of justice necessarily different from the thing itself?

Regardless of the answer to that (for Lutheranism I suspect it would be a grim one), pointing our our psychological predilection toward hijacking justice to serve our self-conceptions does not imply it doesn’t exist – only that we’re terrible at recognizing/implementing it. Anyway, in the final analysis, I would just say I think our concept of “deserving” is culturally conditioned (and that phrase smacks annoyingly of relativism to me, too – though I think it’s true here) and so tinged by our self-justifying projects that we cannot really use it as a starting-point in practice. I think Victor Hugo manages to use it as a starting-point – it’s hard for the rest of us though. So maybe our difference is anthropological – but we’ll talk more next time you’re around. Looking forward to it.

Thanks man. I really appreciate your prompt response. And yeah, actually (after reading it a couple of times), I think that helps clarify some things for me. I agree completely that our human ways of understanding and doing (retributive) justice are often, sadly, marred. So, as you say, ‘in practice’ we do need to be pretty careful regarding what degree we actually trust and wield our own conceptions of justice and deserving. But given the ‘noetic effects of sin’, wouldn’t the same be true with regard to our conceptions of mercy? Could not one make the argument that, in an increasingly libertarian society such as ours, we are actually misusing mercy to the same (or an even greater) extent, by effectively leaving people to their own self-destructive ways? In an effort to be less ‘judgmental’ and condemnatory of any number of actions, lifestyles, and worldviews, one wonders if we have not succeeded in becoming even less humane than past, more ‘judgment-oriented’ generations (in some ways).

I certainly do not mean to suggest that what sinners today really need is human judgment rather than human mercy. But again, I’m not sure I understand why we must assume that mercy, in practice, is so much more trustworthy? Certainly we can both agree that there are perverted forms of ‘mercy’, just as there are perverted forms of retributive justice. So what we need is a right or ‘just'(!) mercy if we are to be truly, lovingly merciful; just as we need a ‘just’ justice if we are to be truly, lovingly fair.

But again, that’s where we run into your epistemological dilemma. Because you don’t seem to think such things are possible in practice. And yes, perhaps that is where a substantial portion of our disagreement lies. I guess I just can’t see how you can talk about any of this stuff rationally, given the great chasm you imagine between justice in theory (or form) and justice in practice. Man cannot live on theory alone. If we are to understand and accept anything in any real sense, it must be with our hands and feet, our hearts and lives, not just our intellect. Nor is there really any such thing as form without substance, anyway. i.e. We are living out our abstract conceptions of justice and mercy in the real world anyway, whether we want to or not. Heck, even Plato seemed to believe in more of a bridge between the two than you seem to be willing to accept.

I just wonder, if the epistemological gap is really so large–if real justice is really so impossible to imagine in practice–doesn’t it begins to call into the question the basis of the abstract theory as well? Honestly, I think that’s what’s happening in your argument, and why it gives the impression that you don’t really have a belief in divine justice. Theory just isn’t enough.

The reason that Martin Luther’s writing on grace was so powerful; the reason it changed the world is because it arose out of his own personal experience of absolute terror before God in light of his sin. We who wield our conceptions of ‘grace’ today (including myself) are not so often coming from the same place, and it might be good for us to remember that fact. At least, I think, our preaching of grace and mercy would be much more profound–much more like Luther–if we did.

“But given the ‘noetic effects of sin’, wouldn’t the same be true with regard to our conceptions of mercy?” – pretty compelling idea; that’ll be food for thought.

I do think Christianity has a harder time bridging the gap than Plato – ignorance and deficiency of knowledge was the only problem for the Plato of the Meno, but Christianity adds a deficiency of will, a perversion of volition.

The easiest response to your mercy argument would be to say that God’s revealed Word, Christ, is the Word of mercy rather than judgment, and ascribing mercy to the revealed God and judgment to the deus absconditus. But that’s obviously a little problematic in implications, theologically speaking.

Perhaps a more earthed response would follow Forde in building a conception of original sin as ladder-climbing, and saying that our sinful psyches are more attached to law than grace, so justice has a greater potential to go awry – but of course mercy can be its own law, and (human) mercy can sometimes exhibit its own self-righteousness, as I think you’re alluding to.

You bring up a good point with the theory stuff, too. I wouldn’t say justice is impossible to imagine with some degree of precision in daily life; it is impossible to image-ine in its fulness, by definition – unless you want to make exception for those who have had ‘beatific’ visions…

I agree too that Luther’s writing was so powerful because it was earthed. To me, Luther’s statement that the Christian life is one of repentance implies he thought self-knowledge as a sinner was crucial to the experience of grace. Whether or not we may impose that realization on others is a different matter. The traditional view of Luther as pretty individualistic is tough to get around – knowledge of divine justice as it condemns me doesn’t necessarily imply we can speak in those terms about others. Perhaps for Luther, considering more broad notions of ‘deserving’ about others was a distraction/ab-straction from my sin, the realization of which is the root of repentance

Well, I just want to say two things up front: 1) You’re a pretty smart dude. 2) Your responses have been very humble. So thanks.

Agreed, Jesus’s coming and dying for us certainly strikes me more as a mission of mercy than one of judgment (John 3:17)! And yet, in his coming, he definitely revealed that quite a bit of both needed to be done–i.e. there was quite a bit of both judgment and mercy in his actions and teaching during his ministry, and certainly a full-fledged dose of both on the cross, according to Jesus & Paul (see esp. John 12:31-32; Romans 3:25-26; 8:3-4).

Nevertheless, I do not mean to sound like I am advocating a more judgment-filled understanding of the Christian life! I just want to bring some balance to what often becomes an unbalanced understanding of grace, which threatens the beauty and power of grace at its root.

Personally, I have begun to wonder if the reason that Paul (and, not to mention, Jesus) tends to interpret the cross according to the intertwining accomplishments of judgment and mercy is because the two are not so much fundamentally opposed (I know I’m sticking my neck out with that one!), but rather interdependent components of the unified, love-centered redemption that Christ came to bring. i.e. It is no true mercy to “accept a person as he is” if you also “leave him as he is.” A person’s sin must be condemned to death if that person is to remain alive. The Lamb of God came to take away ‘the sins of the world’, not merely the condemnation of those sins, otherwise all would be even worse than before. Indeed, condemnation was the first step in removing those sins from us so that we might be mercifully spared in the process. Here’s Paul in Romans 8: “By sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh and for sin, he condemned sin in the flesh, in order that the righteous requirement of the law might be fulfilled in us, who walk not according to the flesh but according to the Spirit” (8:3-4). That, I think, is justice for the sake of mercy. A merciful justice and a just mercy which reveals that both have been made ministers of the inexorable Love of God in Christ.

And this profound, complex redemptive reality is not something that we simply know, but something, according to Paul, in which we ‘walk’. So theory and practice meet, in the same way that God, in all his loving justice and mercy, met us in the person of Jesus. In fact, I think, Jesus’ incarnation (including his death/resurrection) is the very reason that we as Christians must say (much more than Plato!) that the epistemological gap between the abstract and the concrete has been overcome. Jesus overcame it for us (‘Myth became fact’ as Lewis put it), so that now we may live in real reality–so that now we can experience real love, real justice, real mercy, even if the fullness of those realities is yet still to come.

One more thing (sorry): I think our ideas of mercy CAN lead us just as far astray as our ideas of justice, inasmuch as we insist on having the one without the other. If we really want the gospel to be an ideology of grace and mercy–just grace and mercy–then the most natural thing to preach is that Jesus is our deliverance FROM God rather than TO Him. And that, I think, is indeed what we are tempted to do quite often. Jesus becomes the ‘revealed God’ (as you were saying) of mercy who sets us free from the ‘hidden God’ of justice. Of course, in our sinful nature, that’s exactly what we all want anyway–not to be delivered from sin, but to be delivered from God! So certainly it’s a theology that has the potential to catch on like wildfire! But of course, that’s not what we want. So, in my view, we’ve got to find a way to preach Jesus, not as the merciful answer to the scary hidden God of Old Testament Law, but to preach Him as Paul does: “the image of the hidden God” (Col. 1:15) in all his fullness, both just and merciful for the sake of his Love, delivering us “out of my sin and into Thyself” as the hymn says.

Also, I just want to say how blessed I feel to be able to have a discussion/debate like this with you, man. I don’t get to do it very often, which is perhaps why I felt the need to write so much and sort of dump on you. But I appreciate your playing along. So thanks again.