And of course many of us invest our egos in our vehicle–whether driving ovate maxivans, equine pickups, or phallic coupes. Whether cars can continue to do that cultural work–can continue to serve as the ultimate symbol of consumption and success–remains to be seen.

This comes from Daniel Albert’s “Finding the Robot Chauffeur,” a new post over at n+1 regarding the atmospheric change in the automotive industry, from brawn or beauty, to driver assistance and driver safety. In the short piece, Albert presages the new kingdom of the computerized car, and invites the shift, saying, “The robot cars are here. If only we’d let them drive.” His argument is that America, contrary to nostalgic denial, has never much liked to drive, and always looked for ways to do otherwise. The age of the car and driver is misremembered, illusory: cars, like horses, were just ways of getting around.

I can’t help but think of the muscle car, misremembered. Forget James Dean’s 1949 Mercury in that famous chicken scene in Rebel without a Cause. Forget McQueen’s iconic ’68 Fastback chase in Bullitt. Forget Two-Lane Blacktop. Forget The Toad’s ’58 Impala in American Graffiti. Forget American Graffiti all together. And Smokey and the Bandit. And Vanishing Point. And The Dukes of Hazzard.

And forget those throwback hat-tips of this era, too, even. Forget that entire Transformers franchise, centered around the (orange) Chevy Camaro. Forget that the entire Fast franchise was begun not by Vin Diesel, but his godly 1966 Ford GT40. Forget Gosling’s ’73 Chevelle Laguna in Drive. And Blade? Do you remember Wesley Snipes in Blade (1998)? Sure you do! What did the daywalking Vampire-Man drive? A beautiful muscle car: the 1968 Dodge Charger.

Maybe it’s just the movies, though. Maybe Albert is saying that pop culture tends to dishonestly remember “the driver.” Or maybe Albert is simply saying the times have changed and cars like the muscle car are now defunct. I’ll grant him that one, at least; the contemporary muscle cars still around us–the Camaro, the Charger, the Mustang–are hideous. They are the Pop-Tart kids of the old ones, all plasticky and air-puffed renditions of something you feel you ought to recognize. And today we don’t want speed as much. We would rather see on tv a slim-fitting Fiat that’s footprint-friendly, or a phenomenally large pickup that can pull a spacecraft over a bridge. But to say that Americans don’t like to drive? That’s where people, and not just pop culture, are going to take their stand. We may be in the age of digital assurance or eco-awareness, but we’re still looking for ways to drive, even impractically drive.

Albert does make a good point about traffic regulations and laws, saying that automobiles allowed the government to direct communities:

Government will have to rethink much of the regulatory regime that surrounds cars and driving. This is a bigger problem than you might imagine because so much of our system for regulating traffic is not really about making traffic smoother or safer. It’s about social control.

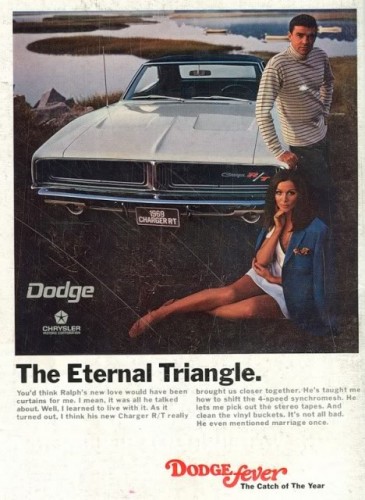

Driving has always been intended for practical efficiency, for getting more done quicker. Driving meant one could live out of town and commute, that one’s life wasn’t ultimately constrained by where one worked. Having a car was a privileged power; it allowed a family to accomplish more for less. But like any power the car was manipulable–it provided power to its driver and his/her intentions–and, like the electric guitar or the television, the eight-cylinder engine became a means for subversion and escape. It became an expression of American emotion–of sex, of loud angst, of impulsive and harried denial. The V-8 became explicitly enjoyed for its im-practicality, and the muscle car was its most American kind of impracticality.

Driving has always been intended for practical efficiency, for getting more done quicker. Driving meant one could live out of town and commute, that one’s life wasn’t ultimately constrained by where one worked. Having a car was a privileged power; it allowed a family to accomplish more for less. But like any power the car was manipulable–it provided power to its driver and his/her intentions–and, like the electric guitar or the television, the eight-cylinder engine became a means for subversion and escape. It became an expression of American emotion–of sex, of loud angst, of impulsive and harried denial. The V-8 became explicitly enjoyed for its im-practicality, and the muscle car was its most American kind of impracticality.

The ten year span from the mid-60s to the mid-70s marked the boom for the American muscle car, the first (arguably) being the 1964 Pontiac GTO, though many say its beginning goes as far back as the ’49 Rocket 88. The GTO in ’64 was basically a $300 option package for the Pontiac Tempest, a small two-door, that gave it a big, 389-cubic-inch V-8 engine, wider wheels, a Hurst shifter, a hood scoop, dual exhaust, chromed valve covers. The GTO itself was a rebellion to their corporation’s (General Motors) policies–because Pontiac had been snuffed from the racing field, the young management there wanted to race anyway, so they designed a car that could do it on the street. They found a loophole, and put a larger engine in a smaller car–and because it was an option package for that small car, it slipped under the radar.

The “muscle car” is generally defined as a two-door, mid-size or full-size coupe with a large-displacement racing engine. Like a thoroughbred, the muscle car is a lot of power–too much power–on much slenderer legs and, also like a thoroughbred, almost entirely useless for practical (or legal) work. At the same time, they are misfits in the racing industry, too: muscle cars are not “sports cars” (think BMW’s M3 coupe) and they aren’t “GTs” (think Porsche’s 911). They aren’t nimble and they certainly aren’t refined. They are affordable sedans that have been souped up to ridiculous proportions, to do nothing but go really fast and make a lot of smoke. A muscle car is exactly how it sounds, in the youngest and most impulsive way–an automobile living beyond its means. It is the gym rat of cars–useless brawn, loud, sexy exhaust pipes–heroic because they said so. They put flashy names on themselves, to be in the class with all the old Italian names: gran-turismo, to-ri-no, ca-ma-ro. They don’t necessarily deserve to be there–they can’t handle corners too well, they blitz down a straightaway but they’re still, all in all, street-legal “family cars”–but they insist on it. Once they received their recognition, and more people found them at drag races and drive-ins, the names began to take an all-American life of their own. Firebirds and Cyclones and Challengers, and Dusters, yes; but also particulars years and models and specifications earned mythologies of their own, heroes begetting heroes, called Boss, The Chief, The Judge, The Machine.

My dad still has his blue Camaro–a 1970 Z-28, 350 LT-1, V-8 with 360 horses. It’s the same engine that was in the Corvette that year, and my dad bought it four years old, for 3 grand. It is an intimidating thing to drive. There is no power steering, of course, and the vinyl seats are almost punk-puritan. There’s nothing fancy, but that almost makes it sexier–it’s just speed. It’s amazing that the Camaro, with those kind of specs, is still called the “pony car” to Chevy’s larger model “muscle car,” the Chevelle SS.

So the muscle car evaded “social control” by way of traffic, simply by refusing to be practical. And this is always sexy. That the focus on speed, power, sex appeal, straightaways, road trips came in a time of growing rules and regulations–not just traffic limitations, but moral and social ones, too–is natural. It is certainly an attractive thing, like Elvis Presley on Ed Sullivan or Easy Rider’s American Dream, to see what was once believed to be “safe” media subverted or exploited by rebels. But the muscle car is also sexy, and profoundly honest, because it is not subtle in its suggestions. The muscle car is so plainly the driver’s stand-in: the driver as he wants to be, the driver rebelling against his own constraints with the brute force of a big engine. To represent ourselves so brashly, with speed and power and independence, to such a grotesque and even needless degree, is endearing in its transparency. It is lovable. Hazel Motes says it best in Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood:

No man with a good car needs to be justified!

So, yes. The robot cars are coming. And, surely, “the ad agencies will come up with new pitches” to make Google-driven cars the next way to invest our egos. But we are always going to want to ride a fast car with a lot of horses, or something like it, because we always want a stand-in. The American will always want a machine to elude the law, and the American will always need a something to make him or her bigger, faster, and sexier. This human impetus to drive will not change with the next fleet of city-safety automobiles. We may see it in commercials now, the push to “Go Places Safely,” the proposal for “Blind Spot Monitors” and “Lane Keeping Assist” and “Pre-collision systems,” but we’re always going to play chicken, and we’ll always want a car, like Cadillac’s new ads, that “blows the doors off.” You say we want safety? The muscle car has taught us better.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pA4ymmXa8rs&w=600]

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wk9SZbrh_Tg&w=600]

COMMENTS

2 responses to “Grotesque Rebellion: The Legacy of the American Muscle Car”

Leave a Reply

A lot of fun to read, Ethan, especially after I went to a concours d ‘elegance for the first time last week–huge event with a lot of impractical and expensive yet beautiful cars to drool over. Seinfeld’s new show Comedians in Cars … is also currently tapping into this American love affair.

I dream not of the unbeatable car but the unbeatable driving licence. I have a fondness for slow, boring, practical cars which I have been known to drive quite fast. Often. I would love to be able to do this without the legal consequences that derive from laws made and enforced by dullards who can’t drive and assume that no-one else can.

I nonetheless remain fascinated by the fantasy of the powerful car. Why do so many slow drivers feel the need to own these fast cars? Most of them are not particularly exciting or adventurous drivers; indeed many are quite unskilled, as one discovers as one shoots past them around corners driving a car that they would consider too slow and tame. Nowadays all cars seem to be plentifully supplied with power, just as our roads are coated with an ever-deepening layer of police with radars. If driving fast is dangerous we are all dead, and I am deader than most.