“Trauma is not just the result of major disasters. It does not happen to only some people. An undercurrent of trauma runs through ordinary life, shot through as it is with the poignancy of impermanence. I like to say that if we are not suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, we are suffering from pre-traumatic stress disorder… One way or another, death (and its cousins: old age, illness, accidents, separation and loss) hangs over all of us. Nobody is immune. Our world is unstable and unpredictable, and operates, to a great degree and despite incredible scientific advancement, outside our ability to control it.”

Thus reads one of the key paragraphs in Mark Epstein’s exceptional “The Trauma of Being Alive”, which appeared in The NY Times, a true must-read. The occasion for the observation was a conversation that Epstein had with his elderly mother, who admitted to actively grieving for her husband, four years after his death. For Epstein, a psychiatrist and author of the brilliantly titled The Trauma of Everyday Life, his mother’s admission contained a revealing element of self-reproach, pointing to the largely unspoken (but nonetheless powerful) little “l” law about the limits of acceptable grief. Of course, you don’t have to be familiar with the letters of St. Paul (and the centrifugal outworkings we’re so fond of pointing out) to know that the pressure we put on ourselves–and others often reinforce, consciously or not–to “get over” something traumatic tends to prolong the suffering:

My response to my mother — that trauma never goes away completely — points to something I have learned through my years as a psychiatrist. In resisting trauma and in defending ourselves from feeling its full impact, we deprive ourselves of its truth. As a therapist, I can testify to how difficult it can be to acknowledge one’s distress and to admit one’s vulnerability. My mother’s knee-jerk reaction, “Shouldn’t I be over this by now?” is very common. There is a rush to normal in many of us that closes us off, not only to the depth of our own suffering but also, as a consequence, to the suffering of others.

When disasters strike we may have an immediate empathic response, but underneath we are often conditioned to believe that “normal” is where we all should be…

In 1969, after working with terminally ill patients, the Swiss psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross brought the trauma of death out of the closet with the publication of her groundbreaking work, “On Death and Dying.” She outlined a five-stage model of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance. Her work was radical at the time. It made death a normal topic of conversation, but had the inadvertent effect of making people feel, as my mother did, that grief was something to do right.

[As an aside, this is a classic, and deeply unfortunate, example of the human tendency to turn something descriptive–Kuebler-Ross’ five stages of grief–into something prescriptive, AKA to fashion a measuring stick out of an observation almost automatically (see also: default readings of scripture).] Epstein continues:

Mourning, however, has no timetable. Grief is not the same for everyone. And it does not always go away. The closest one can find to a consensus about it among today’s therapists is the conviction that the healthiest way to deal with trauma is to lean into it, rather than try to keep it at bay. The reflexive rush to normal is counterproductive. In the attempt to fit in, to be normal, the traumatized person (and this is most of us) feels estranged.

In other words, there is something instinctual in the wake of tragedy, or at least something deeply internalized, that condemns us for our sadness, a voice that says, “time to get back to normal” or worse, “you’re doing it wrong!” This idea–that grief is like a class that can be aced or flunked, something to be controlled or mastered–sounds patently silly when you say it out loud. But as we all know, the ridiculousness rarely makes the voice (of the law) any less seductive or counterproductive in the moment. Grace, at least in theory (or in practice, e.g. when refracted by a good therapist or pastor), silences the question of “should” and gives a person such space that they might “feel it to heal it”, as the saying goes. This is nothing fresh, of course, but it bears repeating–so counter to our inclinations does it run. What separates Epstein’s piece from the majority of articles about grief, however, is the next part, where he “maximalizes” the issue:

While we are accustomed to thinking of trauma as the inevitable result of a major cataclysm, daily life is filled with endless little traumas. Things break. People hurt our feelings. Ticks carry Lyme disease. Pets die. Friends get sick and even die… The first day of school and the first day in an assisted-living facility are remarkably similar. Separation and loss touch everyone… Trauma is an ineradicable aspect of life. We are human as a result of it, not in spite of it.

Now, granted, the word “trauma” is probably being used a tad recklessly here, and some of these assertions could be interpreted as insensitive to, say, soldiers returning home from Iraq. There may indeed by some over-psychologizing going on. And Lord knows that there’s very little visible difference between someone who has found a way to embrace their grief and someone who is simply hiding in it. But that doesn’t mean Epstein is off base when he claims that an element of trauma informs human nature on a foundational level (in the form of death), and that attempts to minimize or dismiss all echos of loss, however petty they may seem, are ill-founded. He is on very solid ground.

In fact, if this all sounds like a page ripped from Tullian Tchividjian’s Glorious Ruin, that’s because it sort of is. One of the driving ideas in that wonderful little book is simply that suffering and trauma are daily human realities. We may doff our hat and pretend these things are self-evident, but they aren’t. We struggle against this truth with every fiber of our beings, more often than not compounding it in the process. We cast suffering as the exception rather than the rule. We minimize and moralize it. We build all sorts of mental and religious architecture to avoid being honest about what’s actually occupying our emotional energy; whether we evade our trauma because it seems too trivial or because it seems too painful to dwell on, we’ll do anything but face it head-on. And as Tullian astutely points out, where there is no honesty with ourselves and others, honesty (and intimacy) with our Creator is elusive at best, and any talk of a relationship with God remains an abstraction. Of course, there are plenty of non-religious ways we minimize pain and trauma–we talk about the so-called “benefits” of anxiety, anger, depression, for example–but Tullian is at his best when exposing a few of the Christian ones:

[We minimize pain when] we project a hierarchy of suffering onto God Himself… Translated into spiritual terms you might say, “I’m having a bad day, but at least I don’t have pancreatic cancer. God has too much on His plate for me to bother Him with my petty concerns. He clearly cares more about starving children than He does about my seasonal depression.” There may be something noble about keeping things in proper perspective, but soon we are dictating to God what He should or shouldn’t care about. And it is a slippery slope! Eventually we’ll edit our prayers along these lines, as though we were giving a political speech, rather than simply speaking with our heavenly Father. If the only things that qualify as suffering in your life are natural disasters or global warfare, you will soon find yourself plastering a smile on your face and nodding over-enthusiastically whenever someone asks you how you are doing. Shiny, happy Christians are insufferable, pun intended.

The second barrier [to honesty about our suffering] is related and, like the first, by no means restricted to Christians. We establish other boundaries for suffering, such as time limits and phraseology. In his book Shattered Dreams, Larry Crabb relates hearing a pastor say, “We must pray for our dear sister. She lost her husband two months ago and is still battling grief. She should be over it by now.”

Grief, of course, is not something that operates according to a specific time frame, and it seems cold to suggest otherwise. Yet when we do not grasp that God is present in pain, we eventually insist on victory or, worse, blame the sufferer for not “getting over it” fast enough. This is worse than a failure to extend compassion; it’s an exercise in cruelty. (pgs. 74-75)

Maybe you read Epstein’s piece, or Tullian’s book, and wonder if ‘the lady doth protest too much’, if it all sounds a bit morose and “first-world”, i.e. cavalier and excessively downbeat, maybe even to an entitled extent. Do they really expect us to prefer a world full of Eeyores to one where everyday trauma is moderately suppressed? A reasonable objection, yet I doubt that’s the end-game. In fact, in tone, both of these men come across as anything but sullen. Elsewhere we’ve talked about how such sober outlooks are commonly employed in the service of those who are isolated in their grief, out of a sense of compassion and love. While I can’t speak for Epstein, I love the way Tullian ends his chapter on “Suffering Honestly”, and not just because he quotes at length from one of our posts, Sean Norris’ story of an encounter with a beloved seminary professor (one guess). First paragraph is Sean, second is Tullian:

“We are all sufferers under our sin.” It cut straight through me. I almost didn’t believe him. It was the first time that someone had validated the pain that I had experienced as a sinner. It was the first time I felt truly addressed. Here I was, a western, white, suburban, Christian male. According to the Christianity of my upbringing, I had never really suffered in my life. I had never experienced starvation or extreme poverty. I had not been persecuted for my faith. I had not been harassed or wrongfully imprisoned, and so on. But in a single swipe, my teacher dismissed all of that. He told us to stop comparing ourselves to others, stop comparing ourselves to people in the third world, to people who are “really suffering.” He leveled the playing field and destroyed the categories and false hierarchies I had put myself in. Instead, he told us the truth. The only point of comparison that truly mattered was the perfect demand of the law. In that light, there was no exception, we were all condemned and, as a result, we all had the same need…the need for grace. I was pointed back to Jesus Christ and His cross, the one who knows our suffering and chose to suffer it once and for all, so that our stories would cease to be about guilt and shame and would become about forgiveness and freedom. I learned that day that the gospel was for me, and it changed my life forever.

God is not interested in what you think you should be or feel. He is not interested in the narrative you construct for yourself, or that others construct for you. He may even use suffering to deconstruct that narrative. Rather, He is interested in you, the you who suffers, the you who inflicts suffering on others, the you who hides, the you who has bad days (and good ones). And He meets you where you are. Jesus is not the man at the top of the stairs; He is the man at the bottom, the friend of sinners, the savior of those in need of one. Which is all of us, all of the time, praise be to God! (pgs. 89-90)

COMMENTS

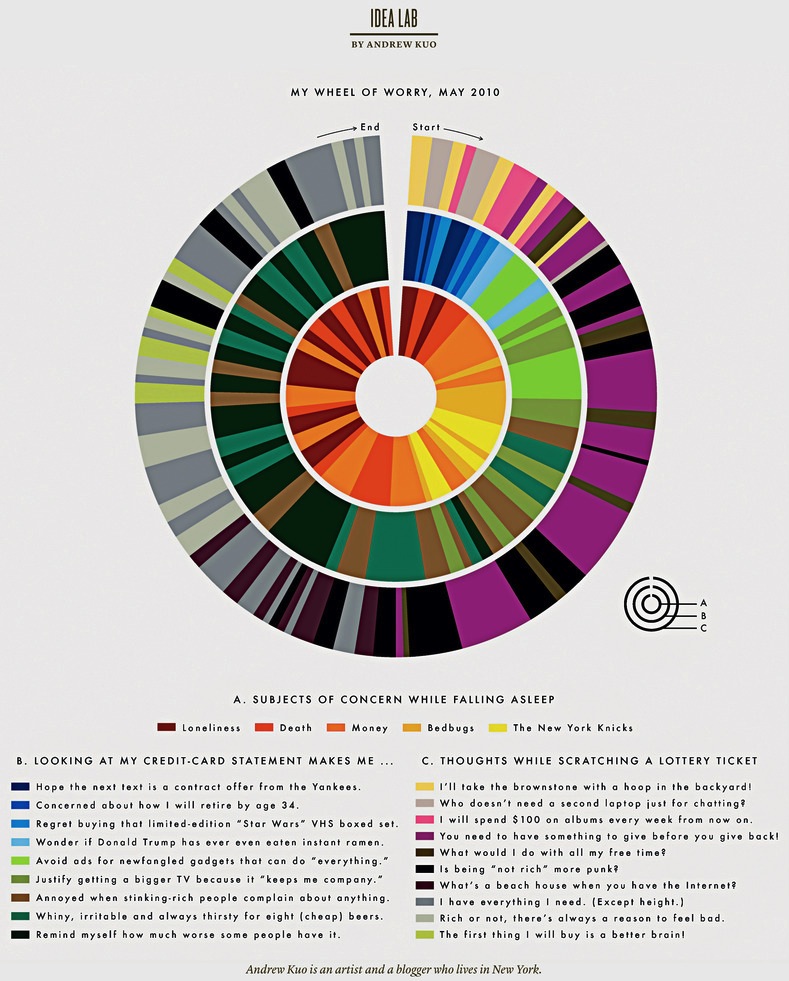

9 responses to “Wheels of Worry, Everyday Trauma, and the First Day of School”

Leave a Reply

Thanks Dave. An awesome post!

Amen & amen

If I may, one more time…this excellent post comports so well with PZ/s podcast Transcendence…no one can win over the Antagonist…we need a spiritual beacon.

Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me, a sinner.

Watching Friday Night Lights as I am reading this post, a sort of convergence. FNL is trauma writ small across the screen, not the big “third world” trauma referred to, but the sense that losing and loss are just “normal” while victory and triumph are episodic and often pyrric. I guess that’s why grace shows up in such a palpable way in the show… and in life.

Well said……I’ve never thought of victory and triumph as episodic – that makes a lot of sense.

Wow, what a stunningly awesome post. I’ve been following Mbird for years and this has to be one of the best.

Perhaps one of my favorite pieces yet, Dave.

Thank you, this is great work. Today marks six months since my boyfriend went to be with the his Savior and your words came at such an opportune time. This is so well thought through and refreshing. I’m grateful for such clear truth. May God continue to bless your work.