You can watch the focal length elongating in 12 Angry Men. This makes the close-ups (which come more and more frequently as the film furthers) become more personal, more detached from the judicial background. Also you can see that the camera shots, while doing this, are also beginning to take a different angle. The courtroom shots (which make up only the first two minutes of the 97-minute movie) and the early jury room shots are from above. By the end, you are looking upward, from below, at the faces of these sweaty men. It’s not just claustrophobia that’s created in 94 minutes of a 1957 jury room. It is empathy. We watch the transformation (Is it a descent? An ascent that is a descent?) of a group of men from righteous certainty to righteous doubt, all because jury duty has forced them to see themselves.

You can watch the focal length elongating in 12 Angry Men. This makes the close-ups (which come more and more frequently as the film furthers) become more personal, more detached from the judicial background. Also you can see that the camera shots, while doing this, are also beginning to take a different angle. The courtroom shots (which make up only the first two minutes of the 97-minute movie) and the early jury room shots are from above. By the end, you are looking upward, from below, at the faces of these sweaty men. It’s not just claustrophobia that’s created in 94 minutes of a 1957 jury room. It is empathy. We watch the transformation (Is it a descent? An ascent that is a descent?) of a group of men from righteous certainty to righteous doubt, all because jury duty has forced them to see themselves.

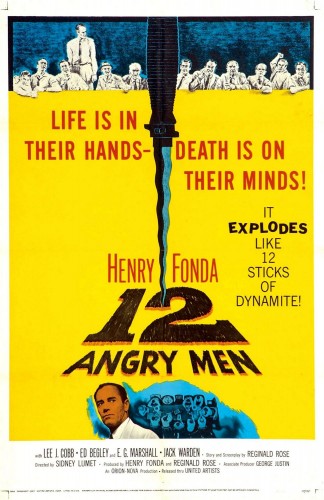

Perhaps you’ve seen it; if you haven’t, you should. It’s free to watch on YouTube (see below). While it lost out to Bridge over the River Kwai in every category that year, Henry Fonda said it’s among the best films he ever made, and the sheer feat of creating the kind of intensity it does, in one room for an entire film, is a constraint so well-handled it alone merits a watch.

To set up the jury room, an eighteen-year-old boy is being charged with first-degree murder of his father. The evidence for the prosecution, while perhaps not perfectly conclusive, seems to heavily favor the boy’s guilt. Twelve men of varying occupations and American backgrounds (a stock broker, a garage owner, a painter, a watchmaker, etc) are led into the jury room to come to a unanimous decision on the boy’s fate. (One character, the ad-exec, played by Robert Webber, looks uncannily like Coach Taylor.) While gladhanding smalltalk begins the room’s dynamic, it becomes quickly clear that one man—the lanky Henry Fonda, an architect—stands aloof in the weight of this democratic responsibility. Wearing a white suit, he is the only man who initially votes “not guilty” amidst 11 other thumbs down. What takes place then is the meat of the film.

A lot can be said about the morality-tale implications of the film. The eighteen-year-old is a “slum kid,” of unknown ethnicity. Many of the strong opinions in the jury room deal with racist generalizations, people-like-that kind of analyses that explain away justice in service to privilege and fear. Some might say this is a film about prejudice (pre-justice)—that the difficulties of American democracy and justice are rooted in the haves’ vocal power over the have-nots.

It is shortsighted to say this is a film about social justice, though, without talking about its deeper interest in the nature of confirmation bias. It seems all along that Reginald Rose wanted to show, in his teleplay, that human beings analyze information under their own preconceptions. This has less to do with racism or classism than it does with the propensity to avoid condemnation. We see these pre-formulized judgments everywhere: what is your opinion of the New York Yankees? Boarding school kids? Pickup trucks? Hip hop? Modern art? Scriptural Inerrancy? Fast food? We concretize opinions and, always to be right, curve the news we hear to fit the judgments we’ve preserved. When Juror #10 (Ed Begley), the garage owner, explains the guilt of the boy, it is not because any particular bit of the evidence was conclusive. The boy himself was conclusive before the examinations took place—he was “one of those,” like those who work in his shop, the ones who steal and kill and have no moral code. His mind is made up, and even as other jurors’ minds are changed, his anger worsens to justify the worldview that has made it all make sense before.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dzhH2hlNSfs&w=550]

This is true not just for the classist but for the goof, too. Juror #7 (Jack Warden), with a ball game to get to and jokes up his sleeve, lives under the preconception that everything can be sold with jokes, and nothing matters. Juror #12, the ad exec, believes that this problem does not so much concern him as he concerns him, and so he minds his business without committing much of an opinion without waffling. The stock broker needs clear facts to make any decision, the painter follows his gut. The way we make sense of world must continue to make sense, or what? Start again? And at the same time, the tenacity to which one holds on to his form of living his life in the world is directly related to how quickly he releases his verdict of guilt. The man for whom this verdict is the most “personal” is also the furthest from changing his mind.

In this way the film says these men portray a justice that is autobiographical. And the stickiest (and most angry) man in the room is Lee J. Cobb’s character, the third Juror. Troubled by his own estrangement as a father, and by his own anger issues, his life story most closely fits the courtroom story they’ve just heard. In order not to feel the condemnation he feels this teen deserves, he attempts to silence his own autobiography from his take on the trial. In reality, though, the zealous vendetta he seems to have upon the boy is a reaction to the blame he’s placed upon his own prodigal son.

The architect’s job, then, is to be the force of deconstruction. Henry Fonda’s isn’t so much the Christ figure of indelible innocence, but the one doodling the sand, a distracting force to allow the condemners a chance to see themselves. For the white-coated, soft-spoken architect, empathy cannot come without first the deconstruction of one’s autobiographical sense of justice. And this cannot happen without first seeing oneself. The architect takes Juror #3 to the very height of his anger, to the very point of saying “I’m going to kill you!” only to see that he is the very condemned he has condemned. This is the great reversal in the film. To see that empathy for the condemned can only find itself true when one sees oneself there, too.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s0NlNOI5LG0&w=550]

COMMENTS

One response to “Mockingbird at the Movies: 12 Angry Men (Minus One)”

Leave a Reply

Wonderful film.

And a great job in your review of it.

Thanks.