This one comes to us from Sam Bush:

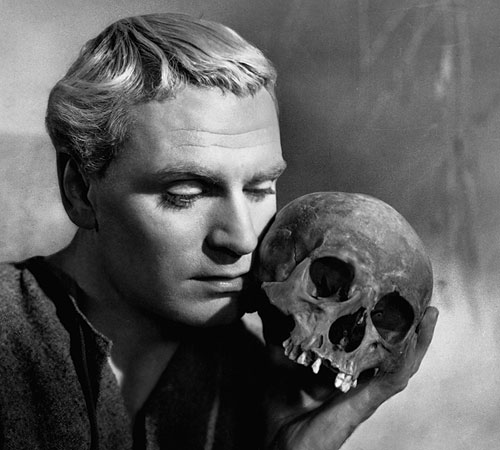

I cringe to think of how much time I’ve wasted making decisions. The hours I waste paralyzed in the cereal aisle easily match the time I spend eating cereal (and I always end up choosing Oatmeal Crisp anyways). Personally speaking, the ratio of time spent agonizing over a decision to time spent enjoying the outcome is roughly 7:1. The debilitating fear that leads us to second-guess is nothing new – just ask Hamlet or J. Alfred Prufrock – and, of course, little has changed about us as people. The “paralysis of analysis” is today’s hippest diagnosis among therapists due to our collective inability to make choices, big or small, for fear of living in regret. Other decisions, far more weighty than cereal selection – where to live, who to marry, what to do for a living – can be infinitely more paralyzing. And even if we get the answers right, it often seems we’re still short of finding a solution.

I cringe to think of how much time I’ve wasted making decisions. The hours I waste paralyzed in the cereal aisle easily match the time I spend eating cereal (and I always end up choosing Oatmeal Crisp anyways). Personally speaking, the ratio of time spent agonizing over a decision to time spent enjoying the outcome is roughly 7:1. The debilitating fear that leads us to second-guess is nothing new – just ask Hamlet or J. Alfred Prufrock – and, of course, little has changed about us as people. The “paralysis of analysis” is today’s hippest diagnosis among therapists due to our collective inability to make choices, big or small, for fear of living in regret. Other decisions, far more weighty than cereal selection – where to live, who to marry, what to do for a living – can be infinitely more paralyzing. And even if we get the answers right, it often seems we’re still short of finding a solution.

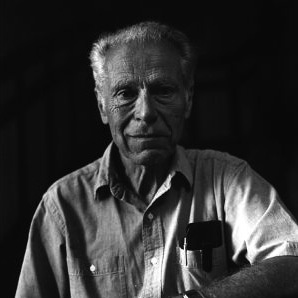

Thankfully for us non-commitals, The New Yorker recently published a piece by Malcolm Gladwell on the brilliantly entertaining 20th century economist Albert O. Hirschman. By trade, Hirschman was a “planner,” consulting heavy-hitting tycoons like the World Bank and the Federal Reserve Board. He studied multibillion-dollar projects and his advice held enough weight to determine the economic fate of several developing countries. Strangely enough, despite his level of power, Hirschman’s theories defended bad planning more than they did expert strategy. Hirschman was fascinated by how some of the most successful outcomes have risen from the ashes of utter and disappointing failures—leaving us to believe that we can never plan perfectly.

We ended up here with an economic argument strikingly paralleling Christianity’s oft expressed preference for the repentant sinner over the righteous man who never strays from the path.

According to Gladwell, Hirschman understood well that people don’t seek out challenges. In fact, more often than not, our decisions are built on “the erroneously presumed absence of a challenge.” Citing examples like an overbudgeted construction project and a failed paper mill (projects that were widely believed to be fail-proof that later became total nightmares), the economist noticed that when things go awry—when we discover the real difficulty of a situation and, unable to turn back, are forced to go through with our decision—unexpected blessings may arise despite our ignorance and poor judgment. This isn’t to say that the ends always justify the means; the pain of failure is excruciatingly painful in the moment. However, accepting uncertainty (i.e. “living by faith”) can possibly help ease the pressure to make the right choice or alleviate regret from making a poor choice. According to Hirschman (who considered himself the anti-Hamlet) you just never really know until you try—and even then, you still won’t really know. Gladwell writes:

Only Hirschman would circle the globe and be content to conclude that he couldn’t reach a conclusion—for a long time, if ever. He was a planner who really didn’t believe in planning. He wanted to remind other economists that a lot of the problems they tried to fix were either better off not being fixed or weren’t problems to begin with.

And just as our failures are covered by grace, so are our victories. Hirschman realized that, since we’re never in control of the outcome of a situation, our successes too are based largely on dumb luck (aka grace).

While we are rather willing and even eager and relieved to agree with a historian’s finding that we stumbled into the more shameful events of history, such as war, we are correspondingly unwilling to concede – in fact we find it intolerable to imagine – that our more lofty achievements, such as economic or political progress, could have come about by stumbling rather than through careful planning.

“Theorizing that the history of human progress is based on dumb luck is all well and good,” you might say, “but how does this way of thinking apply to our everyday lives? There is the value of discernment and good judgment…” To this, I suspect Hirschman would say that no matter how discerning you are, life, in all its unknowingness, is quite capable of throwing you enough “unintended consequences and perverse outcomes” to make you too afraid to even plan a trip to the market (let alone get out of bed in the morning) unless, of course, you are given the gift of faith.

When faith frees us from the fear of failure (alliteration points please?) we’re allowed to do things we would never have dreamed doing. Explaining their family’s decision to leave a comfortable life in Chevy Chase, Maryland on a whim and move to Bogota, Columbia (where Hirschman would work as a development consultant) Hirschman’s wife Sarah wrote, “I think we both somehow feel that it is impossible to know what is best and that the present is so much more important—because if the present is solid and good it will be surer basis for a good future than any plans that you can make.”

I think paraphrasing Hirschman as saying, optimistically, “Take a chance!” or “Go for it!” would be oversimplifying it a bit. Lord knows many of us have regretted plunging into enough unknown depths to make us test the waters first from now on. Hirschman’s way of thinking isn’t valuable because it tells us what to do – it’s valuable because it frees us to simply trust God and live. Whether Hirschman knew it or not, his theories point to a message infinitely more assuring than the blind optimism of “Go for it!” or the empty reasoning of “Everything happens for a reason.” Whatever decisions we make in life, we’re allowed to take comfort in God’s most assuring words: “Fear not. For I am with you.”

COMMENTS

3 responses to “The Paralysis of Analysis vs. the Gift of Bad Planning”

Leave a Reply

Sam- this is so great! I really appreciate the perspective you added to the article, especially the connection to living by faith and not by sight and what that means practically. Really, really cool 🙂

Full alliteration points granted from erstwhile English teacher.

Oh, and splendid piece as well . . . “trust God and live.” Golden.